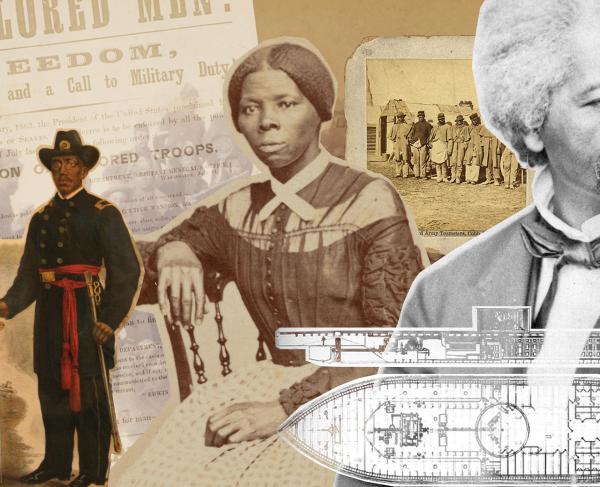

The Battle of Hampton Roads: Then & Now

With the 150th anniversary of the famous battle between the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia now before us, the Civil War Trust recently had the opportunity to speak with noted naval historian and author Craig Symonds about the Battle of Hampton Roads and the historical significance of the first battle between ironclad naval vessels.

Civil War Trust: Poor in industrial resources, why was the Confederacy so interested in constructing steam-powered ironclad warships?

Craig Symonds: Stephen Mallory, the talented and dedicated Confederate Secretary of the Navy, recognized the impossibility of attempting to compete with the Union ship-for-ship in building a conventional navy. He knew the South simply didn’t have the resources or the naval infrastructure to do so. He therefore sought a shortcut by pouring a disproportionate amount of his available resources into a few ironclads that he hoped could break the blockade and secure southern ports. Given the circumstances, and the fact that the Civil War took place at a moment of dramatic technological change, it was a reasonable decision.

John Ericsson’s USS Monitor design was one of many competing ironclad designs before the U.S. Navy. Why was Ericsson’s design chosen?

Craig Symonds: First of all, it was not the only design chosen. The Ironclad Board (as it was called) selected three designs, and all three were built. Besides the Monitor, the Board approved the construction of USS Galena, which proved to be a failure and was later converted back into a regular gunboat, and the vessel that became USS New Ironsides: a conventional-looking frigate that had heavy armor over most of its hull and somewhat resembled HMS Warrior. Ericsson’s Monitor design was the most revolutionary, and several of the Board members were skeptical of it. It was Abraham Lincoln’s implied support for it that probably convinced them to approve it as one of the three.

There were several senior Confederate naval officers who wanted to take command of the CSS Virginia. Why did Stephen Mallory choose Franklin Buchanan as the Virginia’s commander?

CS: To begin with, Buchanan was very senior. He had become a midshipman in 1815 and had nearly-continuous service ever since with a very good record. But in addition, Buchanan was an old sea dog with a reputation for aggressiveness. Given the investment the Confederacy had made in the Virginia, Mallory wanted someone who would seize the moment and take maximum advantage of it.

How would you compare the designs of USS Monitor and CSS Virginia? Which ship proved to be the more effective design?

CS: The two ships were, of course, radically different. Ericsson designed his vessel from scratch, building it to fit his imagined revolutionary warship. For its part, the Confederacy was limited in what it could do, which is why the builders used the existing hull and engine plant of the USS Merrimack as a platform. Moreover, the South simply did not have the machinery to bend heavy metal plate; it could not produce the curved metal plates necessary to fabricate the Monitor’s turret. As a result, a casemate design—essentially an iron fort on top of a conventional ship’s hull—was the only kind of ironclad they could produce in a short period of time. As to which was “more effective”: each type had strengths and weaknesses. The Virginia was a better gun platform because it could bring more guns to bear on a foe; the Monitor with its shallow draft could go places the Virginia could not, but it had only two guns which limited its offensive impact. In the end, neither design lasted very long, though the U.S. Navy continued to build ships it called “monitors” until the late 19th century.

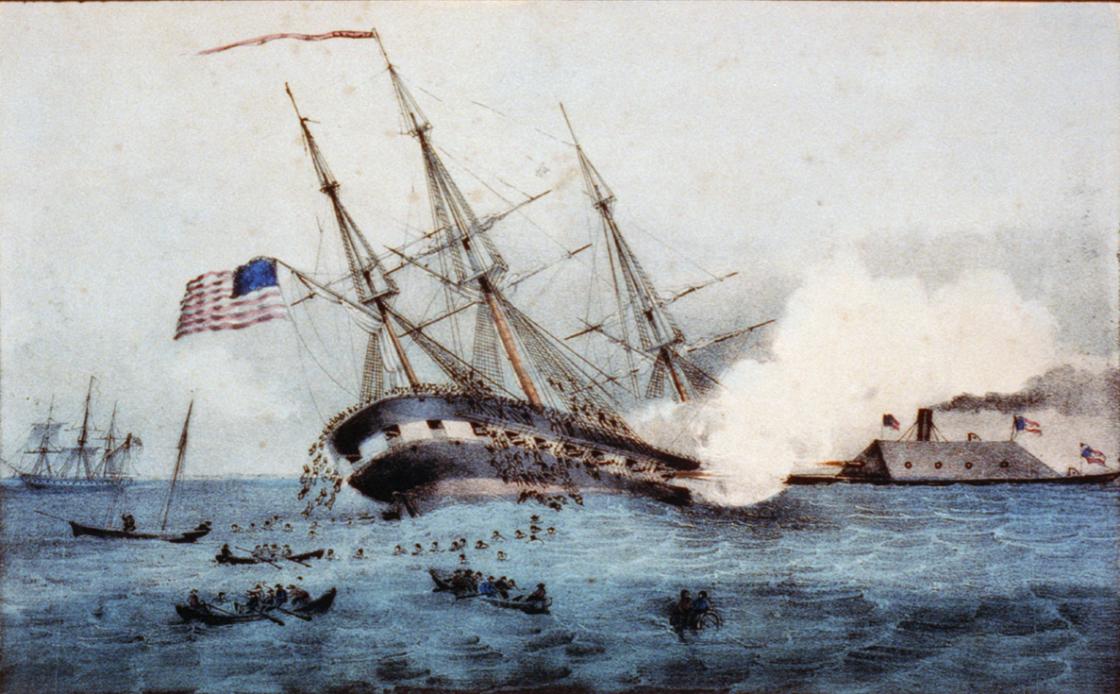

March 8, 1862 pitted the CSS Virginia against wooden naval vessels around Hampton Roads. What was Buchanan’s battle plan for this first day?

CS: Given his character and personality, it is no surprise that Buchanan adopted a straightforward approach: On the Virginia’s trial run, he planned to steam straight at the two enemy warships across the roadstead and smash into the one that he believed was most powerfully armed. If he could sink it with his ram, he would then attack the other vessel with his guns. This is essentially what happened, and it shows why Mallory chose him for command in the first place.

March 8, 1862 proved to be the bloodiest day in United States Naval history up to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Didn’t the US Navy know that the Virginia would be a serious threat?

CS: It did. The Navy had watched the progress on the conversion of the Merrimack into the Virginia with great interest. The reason for the high casualties was, in part, that the Union officers and sailors on the Cumberland and Congress continued to fight even when they ship was in extremis and sinking. The men on the weather deck of the Cumberland continued to fire their guns even as the ship sunk beneath them and went down with her flags still flying. As for the Congress, since Buchanan could not reach her where she was in shoal water, he set her afire with hot shot and many of her crew—including scores of wounded—probably burned to death. Finally, many sailors in the 19th century could not swim, and scores of them drowned even though they were within swimming distance of the shore. The great error made by the Union in this battle was to fight from anchor. As Buchanan learned in the Battle of Mobile Bay two years later, a wooden ship underway is much harder to attack effectively, especially with a ram.

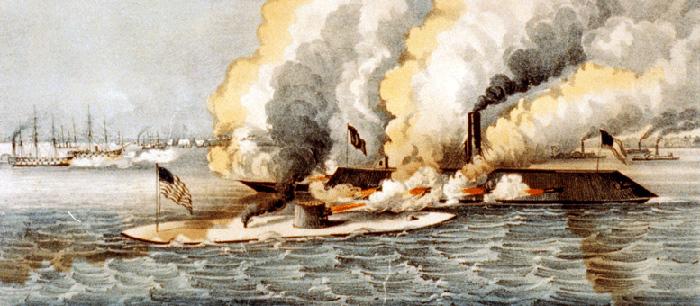

With the USS Monitor now at Hampton Roads, why did the CSS Virginia seem to ignore this new vessel early on March 9, 1862?

CS: With Buchanan wounded, command of the Virginia passed to Catesby ap Roger Jones. Jones’ mission was to finish off the rest of the Union wooden fleet starting with the USS Minnesota which was aground. The Monitor had arrived overnight and was moored alongside the Minnesota, but in the early morning fog it was difficult to identify. Some on board the Virginia thought it was a raft carrying a boiler or a water tank. Only when it began to move toward them did they appreciate it was the Union’s new ironclad.

On March 9, 1862 what was Lt. John Worden’s battle plan for the USS Monitor?

CS: Worden’s job was to interpose his vessel between the Virginia and the vulnerable wooden ships of the Union squadron in the roadstead. He hoped to get close enough to the Virginia that his two big 11-inch guns had a chance to penetrate the Virginia’s armor shield. Beyond that, he had no definite battle scheme and planned simply to adjust to circumstances.

Despite their close range and heavy expenditure of shot and shell, why did this battle end in a draw?

CS: The simple answer is that neither vessel had guns powerful enough to punch through the iron armor of the other. The Monitor’s guns might have been able to do so if Worden had used a full 30-pound charge. But the guns had been proofed only to take a 15-pound charge, and he did not want to risk an explosion of the breech in the confined turret. Each captain also tried to ram the other, but the Virginia had lost is ram inside the doomed Cumberland, and in any event it was too slow (top speed 5 knots) to ram the nimble Monitor. The Monitor did manage to ram the Virginia, but to no serious effect. In short, neither ship could seriously wound the other.

Much has been made about the technical advances of these two ships, but you argue in your book, Decision at Sea, that the advent of ironclads actually had a much bigger and long-lasting impact on naval crews and Age of Sail traditions. How so?

CS: Naval leaders the world around appreciated after 1862 that armored ships could easily defeat wooden warships. That led to a race between increasingly thick iron armor and increasingly powerful naval guns in the late 19th century. Eventually it became evident that the amount of armor needed to deflect shells from heavy rifled guns was so great that ships so armored would be too heavy to maneuver effectively. Today, warships are armored only in a few critical places and rely on technology and weaponry as a defense, not on armor plate.

The real revolution in naval warfare, which proved to be a permanent one, was in the changed roles played by the men (and today women) who manned these vessels. Even at the time, a number of men on board both ironclads referred to their vessels as “machines”. They understood that they had become parts of a machine of war: they fed its engines, steered its great bulk, and handled its guns, but their relationship to the ship had changed. They no longer stood on the weather deck, or climbed non-existent rigging—indeed, none of them could even see their foe. They were quite literally in the belly of the beast. This new relationship of man to machine continued through the 19th century and into the 21st where today men (and women) fly unmanned drone aircraft over enemy territory by operating a joystick at McDill Air Force Base near Tampa. It is a different and much less personal relationship of warrior to warfare.

Learn More: The Battle of Hampton Roads

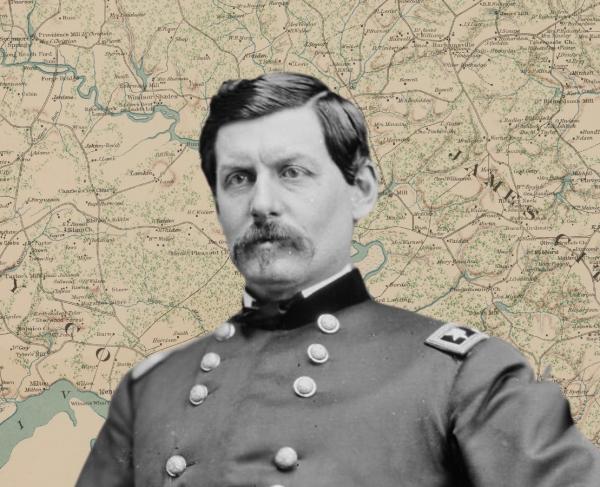

Craig Symonds is Professor Emeritus at the United States Naval Academy where he taught naval history and Civil War History for thirty years. A native of Anaheim, California, Symonds earned his B.A. degree at U.C.L.A., and his Masters and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Florida where he studied under the late John K. Mahon. In the 1970s he was a U.S. Navy officer and the first ensign ever to lecture at the prestigious Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. After his naval service, Symonds remained at the War College as a civilian Professor of Strategy from 1974-1975.

Symonds is the author of twelve books including his newest title, The Battle of Midway. In addition he has written over one hundred scholarly articles in professional journals and popular magazines as well as more than twenty book chapters in historical anthologies. Five of his books were selections of the Book-of-the-Month Club, and six have been selections of the History Book Club. His books have won the Barondess Lincoln Prize, the Daniel and Marilyn Laney Prize, the S.A. Cunningham Award, the Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt Prize, and the John Lyman book Prize three times. In 2009 he shared the $50,000 Lincoln Prize with James M. McPherson. He also won the "Annie" Award in Literary Arts given by Anne Arundel County, Maryland.