The Battle of Malvern Hill

Winston Churchill visited the Richmond battlefields in 1929. Always a perceptive student of military history, the future Prime Minister appreciated the opportunity to examine all of the Seven Days battlefields in person. Of the Chickahominy River, he wrote, “What a surprise! It is little more than a woodland stream; and White Oak Swamp! a thicket with some puddles.” He said little of the individual battles of the Seven Days, but his touring experiences outside Richmond reinforced in his mind the advantages of personally inspecting battlefields. “No one can understand what happened merely through reading books and studying maps,” he mused. “You must see the ground; you must cover the distances in person; you must measure the rivers, and see what the swamps were really like.”

Eighty years later, Churchill’s admonition applies more to Malvern Hill than to any other battlefield around Richmond. The last of the Seven Days battles bears a reputation today grounded on geography: an imposing hill, stoutly defended by Union cannoneers, against which the Confederate leaders hurled waves of infantry in ill-coordinated frontal assaults. All of that is true, but first-time visitors to the well-preserved battlefield inevitably see something different than they imagined. The hill at Malvern Hill is no mountain; it is a gentle slope. Anyone walking in the footsteps of the unfortunate Confederate infantry immediately learns that the reality of the landscape is different than the menacing precipice expected from reading the reminiscences of men who were on the spot in 1862.

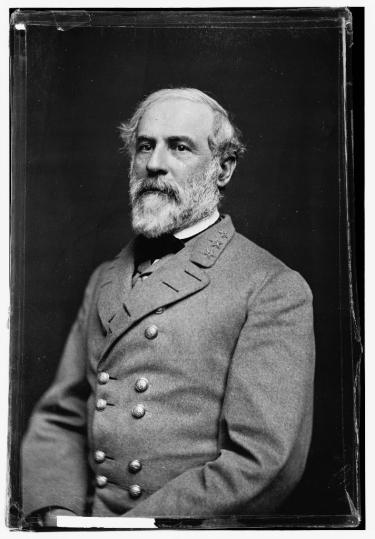

The series of events that reached their denouement at Malvern Hill began on June 26, 1862, when the Confederate army of R. E. Lee initiated offensive operations outside Richmond. “Stonewall” Jackson’s command swept in above and behind George McClellan’s Federal army near Mechanicsville. In the course of 100 memorable hours, the armies marched and fought across a broad corridor east of Richmond. McClellan applied all his energy to removing his army to the James River. Lee was determined to stop McClellan from escaping. An inconclusive battle at Glendale (Frayser’s Farm) on June 30 gave the Union army the time and cushion it needed to reach the river. Mighty gunboats roamed the James, representing safety and continued security for the harassed Federalists.

Lee’s frustration at McClellan’s June 30 escape boiled over on the next morning. He snapped at innocent questions and chafed at delays. His chance to inflict a really crushing, war-changing defeat on the Union army had passed. Now the Federals had stopped atop Malvern Hill, in easy range of the James, and prepared for defense. The men in blue hoped that Lee would be imprudent enough to attack their new position, giving them an opportunity to exact revenge for their weeklong series of defeats.

Malvern Hill is more suitable for defense than most spots in central Virginia. In 1862 the nearest body of Confederate-held trees stood approximately 800 yards from the crest of the hill, and in most directions the distance was closer to a full mile. When Lee’s men finally attacked late in the afternoon, most of them spent a deadly ten or fifteen minutes ascending gently rising, open ground. Union artillerists rejoiced at their opportunity and delivered cannon fire of unprecedented violence on the Confederate infantry.

General Lee had no intention of making a frontal assault directly up the dangerous hill. Initially he developed a scheme where his artillery, deployed at widely separated spots, would drop a converging fire on the Union batteries at the crest of Malvern Hill and silence the menacing guns. Only then did Lee feel that his infantry stood a good chance of carrying the hill by direct assault. The crossfire bombardment failed badly, yet Lee’s men attacked anyway, thrown into the charge after a series of misunderstandings and bungled orders. Lee seems not to have been on the battlefield when the main attacks started. Instead, he was off looking for a non-existent way to get around McClellan’s army and cut him off from the James River.

The precise sequence of events eludes historians even to this day. Some of Lee’s subordinate commanders operated under obsolescent orders. Confusion about the ground and the relative positions of various units further complicated the situation. Whatever the origin, about 35,000 men of Lee’s army eventually stepped off into the assault up Malvern Hill, many of them going forward incrementally, without plan or purpose.

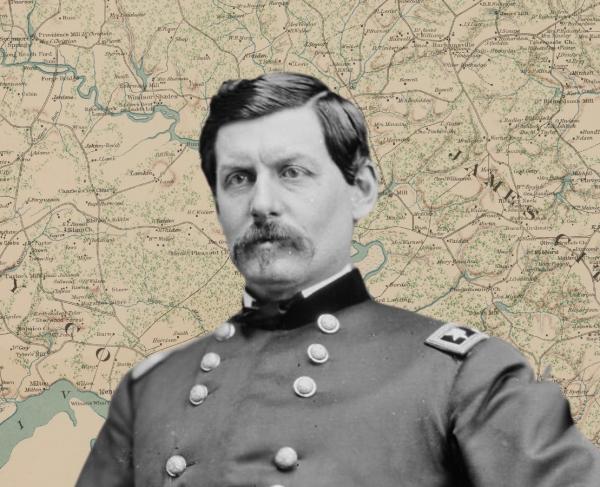

McClellan’s trusted subordinate Fitz John Porter had tactical command of the hill’s defense. General Morell’s division of Porter’s own Fifth Corps filled one side of the hilltop, General Couch’s Fourth Corps division defended the other. Opposite Morell, a vast miscellany of Confederates tested the position. Men from the divisions of D. H. Hill, D. R. Jones, Lafayette McLaws, Benjamin Huger, and J. B. Magruder all charged and suffered. One North Carolina soldier struggled to explain just how awful it was, finally resorting to the ultimate superlative: “The enemy opened the most terrific and destructive fire…that ever any troop met since the world began.” On Couch’s front, wrinkles on the front slope of Malvern Hill could have permitted aggressive Confederates to get within rifle range of the Union cannon. Couch blocked that eventuality by putting his own infantry there, producing short-range firefights with some of Stonewall Jackson’s men.

But the Union artillery line set the tempo for the defense. With room for only about 30-35 cannon on the slender crest of the hill, General Porter still had plenty of firepower to produce winning results. The exposed approach up the hill afforded the Confederates no shelter. As infantry brigades advanced they stalled in front of a wall of cannon fire and fell back. Too often they collided with advancing reinforcements, producing countless cases of “friendly fire” and unnecessary loss. A Georgia survivor with bitter memories wrote about brigades dashing seriatim into the maelstrom, “and those coming last, not knowing who were in front, fired with deadly effect into our friends, very naturally causing a panic in the front brigades, who of course thought they were flanked.”

Periodically a Federal six-gun battery expended all its ammunition, or an infantry brigade fired off all its cartridges. In every instance ready replacements hurried up and seamlessly filled in. Toward dusk a few Confederate brigades found new lines of approach, using the steeply angled face of the western slope to protect their route. Those formations got closer than their predecessors—a few within 75 or 100 yards of the cannon—but no Confederate reached the crest of the hill. When the last explosive musket flashes died out after dark, some 8000 men lay dead and wounded across a few hundred gruesome acres. More than 5000 of that number wore gray, victims of one of the most ill-managed and uncoordinated major assaults of the entire Civil War.

A dense, gloomy rain greeted early risers on July 2. The United States troops were gone, having abandoned Malvern Hill overnight and marched to a secure supply base at Harrison’s Landing on the James River. The Confederates controlled Malvern Hill, the object of their assaults the day before, but Lee wanted to harm the Union army, to inflict a crippling defeat on it. Possession of Malvern Hill did him no good at all, and in a few days the Confederates shortened their lines and moved back closer to Richmond, signaling the end of the Seven Days Campaign.

A Union victory by any definition, the Battle of Malvern Hill produced no critical results in the progress of the war. The outcome of the campaign had not been in doubt before Malvern Hill; only the degree of McClellan’s defeat east of Richmond remained to be resolved. Two defining themes emerged from the battle: the absence in the Confederate army, on that day, of what the modern armed forces term “command and control”; and the influence of the landscape on the course of the battle. Poor staff work, bad communication, wretched tactics, and the erosion of battlefield discipline all characterize the Confederate condition on July 1. They were ingredients in the dreadful recipe that produced defeat for Lee’s army.

More than that, Malvern Hill stands today as a classic example of how the physical environment shaped battles. Every battlefield has nuances awaiting discovery by anyone interested enough to tramp the ground, yet nothing in central Virginia offers greater rewards than a careful examination of Malvern Hill. Its pristine condition and high state of preservation (thanks mostly to the Civil War Preservation Trust, and now to the Richmond National Battlefield Park) make it possible to appreciate and understand why McClellan stopped and fought there, why his troops swelled with sudden confidence, how 8000 men could become casualties in just five hours, and how Lee’s army suffered its last major defeat for at least a year.

_________________________

About Robert E. L. Krick

Robert E. L. Krick is an historian on the staff at Richmond National Battlefield Park. In the 1980's he worked at Custer Battlefield (now Little Bighorn Battlefield) in Montana, and at Manassas National Battlefield. His latest book is Staff Officers in Gray (UNC Press, 2003).

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...