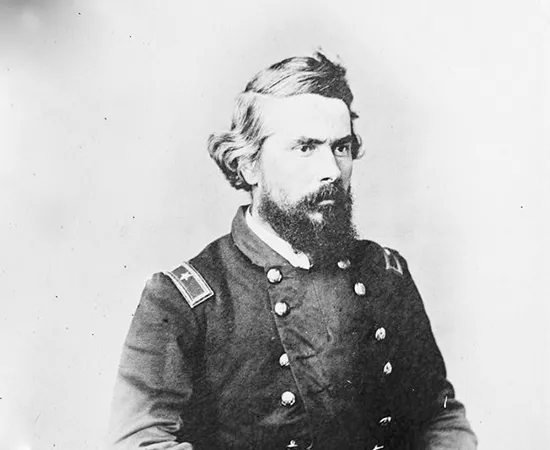

Throughout the Civil War, Florida supplied the Confederacy with beef to feed troops and with salt to preserve it. In 1864, the Union Army, which controlled Forts Taylor and Jefferson in the Gulf, sought to extend its control over the peninsula inland from the Atlantic coast and cut off Confederate supply lines that ran from the Tampa Bay area through north-central Florida to Georgia rail lines. Major Quincy Gillmore, commander of the U.S. Department of the South, wanted to use a mix of black and white troops in the expedition for control of Florida. In addition to cutting Confederate transportation and supply routes, Gillmore aimed to recruit freed slaves into the Union Army and to facilitate the export of cotton and timber to the North. Gillmore selected Brigadier General Truman Seymore, the new commander of the District of Florida, for the operation.

The Union army’s mission was important, not only to disrupting Confederate supply lines, but also to boost support for the war in the North, which was flagging as the 1864 elections approached. Several Republicans even thought that Union military success could potentially move Florida to rejoin the Union. Republicans believed that this campaign could bolster Unionist sentiment that was apparent to varying degrees throughout Florida, inspiring the state to return to the Union under President Abraham Lincoln’s December 1863 Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which required ten-percent of 1860 voters to take the oath of allegiance to gain readmission. If this happened, Florida could then send delegates to the 1864 Republican presidential convention.

Gilmore’s plan to recruit freed slaves represented one of the broader objectives of the Union cause. The Emancipation Proclamation, which went into effect on January 1, 1863, not only freed slaves in states that were in rebellion but also increased efforts to recruit freed slaves “of suitable condition” to the “armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” Black troops were thus crucial to Union military efforts in Florida.

Federal troops under Seymour at Union-controlled Jacksonville were set to march west from the coast in mid-February 1864. Seymour commanded approximately 5,500 troops, including several regiments of black troops: One brigade under the command of Colonel Joseph R. Hawley included the 8th U.S. Colored Infantry commanded by Colonel Charles W. Fribley and numbering 21 officers and 544 enlisted men who were mostly free blacks from Pennsylvania. The other brigade was under the command of Colonel James Montgomery, a radical abolitionist. It included the 2nd South Carolina Colored Volunteers, comprised of free blacks and former slaves from locations like South Carolina and Key West, Florida. The 1st North Carolina Colored Volunteers, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William N. Reed, mustered at New Bern, North Carolina, and Portsmouth, Virginia, and comprised almost entirely of former slaves. And the 54th Massachusetts, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Edward N. Hallowell, who succeeded Colonel Robert Gould Shaw after he was killed at the Union assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. The 54th was comprised of free blacks from Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, and had 13 officers and 480 enlisted men.

Of these black troops, only the 54th Massachusetts had experienced combat. One of its Sergeants, William H. Carney, became the first African American to win the Medal of Honor for his bravery leading troops during the assault on Fort Wagner where he was wounded twice. The other units were green – the 8th U.S. Colored Infantry hadn’t yet completed their training. Regardless, these men knew that an opportunity to prove their bravery under fire loomed, and hopes were high for additional recruitment of black soldiers.

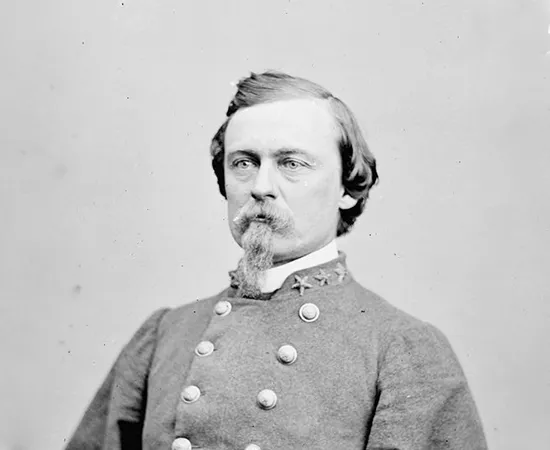

Before marching west, Seymour’s troops at Jacksonville engaged in several raids into Florida’s interior beginning in early February. These actions unnerved Confederate Brigadier General Joseph Finegan, commander of the District of East Florida. Finegan had only approximately 1,500 troops to defend Florida’s crucial supply lines and called for reinforcements. General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard obliged and dispatched reinforcements from Georgia, which made Finegan’s force comparable to the Federals at approximately 5,000, including 4,600 infantry, less than 600 cavalry, and three batteries of 12 cannon. Seymour’s men quickly established a defensive line east of Lake City, Florida, which included Olustee, and anxiously awaited the Union army’s next move.

Generals Gillmore and Seymour, however, had difficulties reconciling their opposing views of both the political and military situation in Florida. Seymour believed that Unionist sentiment was less significant than other Federal officials, and undoubtedly northern Republicans, believed it to be. Arguably, history was on his side. When the Civil War broke out, Lincoln and many other Republicans advanced the “deluded masses” theory, thinking that many white Southerners were duped into secession and war by the slave-owning planter class and that Unionism was latent throughout Confederate territory. This prediction did not come to fruition, and Union strategy changed accordingly. These same beliefs influenced Seymour’s plans. He did not think that an advance on Lake City was possible and feared bolstering Confederate resolve in Florida. Gillmore, upon a visit to Florida, ordered Seymore to bolster Union defenses and to only advance upon his orders. Seymore, however, soon shifted his belief and became an optimist. He proposed marching to the Suwannee River since its railroad bridge was key to Confederate supply. Gillmore objected and dispatched an officer to stop Seymour’s advance, but the message came too late and could not prevent what would become the Battle of Olustee, also known as Ocean Pond.

Seymour and his men set out from Jacksonville towards Camp Finegan, about eight miles west of town, on February 7 and reached Baldwin on February 9. Meanwhile, Finegan’s Confederates constructed earthworks across the Florida, Atlantic, & Gulf Central Railroad east of Olustee Station. The Federals advanced along the railway and a nearby pike, passing Sanderson at mid-day, but the movement stalled when advance Union cavalry encountered Confederate outposts. Union skirmishers from the 7th Connecticut marched towards Confederate entrenchments at Olustee through the open pine forests and swamps of north-central Florida. Confederate cavalry and the 64th Georgia Infantry and 32nd Georgia Infantry, which Finegan ordered to support the cavalry, met the Federal advance, and the Battle of Olustee commenced at about 2:00p.m on February 20, 1864.

Finegan ordered most of his troops out of their trenches, with two Georgians, Gen. Alfred H. Colquitt, and Col. George Paul Harrison, leading the right and left wings, respectively. While the 7th Connecticut heeded orders to fall back, the 7th New Hampshire advanced in confusion having misunderstood orders from Hawley and Confederates unleashed heavy fire on the unit on the Union right. The New Hampshire men broke and ran, contributing to the Union right being crushed. Soldiers in the 8th U.S. Colored Infantry were now at the front on the Union left and the collapse of the Union right left them vulnerable to the brunt of the Confederate attack. The 8th stood firm for a few short minutes, but ultimately fell back under Fribley’s orders having lost approximately 300 out of 500 of its men, killed or wounded, including Fribley. Colonel William Barton’s three New York regiments advanced to the right of the 8th U.S.C.T. after the 7th New Hampshire broke, and the 54th Massachusetts arrived on the field to try to hold the Union line as its band played the “Star Spangled Banner,” temporarily boosting morale. Seymour also ordered the 1st N.C. to the right of Barton’s New Yorkers. They tried to hold the line, but to no avail. An advance was impossible as the unit withstood heavy fire.

By 4:30 p.m., after six hours of fighting, firing halted as the sun began to set. The 54th Massachusetts, 1st N.C. Colored Troops, and 7th Connecticut formed a rear guard as the Union army retreated east. The battered Federals retreated towards Jacksonville having lost 1,861 men killed, wounded, or missing, compared with Confederate losses, which totaled 946. The 8th U.S.C.T. withstood the heaviest casualties of all black troops that fought at Olustee: The unit lost 49 killed, 188 wounded, 73 missing in addition to a national flag. The 1st N.C. suffered 22 killed, 131 wounded, and 77 missing, and the 54th Massachusetts lost 13 killed, 65 wounded, and 8 missing. Federal troops also lost 5 field guns, 1,600 small arms, and 400 sets of accouterments, which Confederate soldiers seized and put to use.

At the beginning of the battle, black Union soldiers feared that, if the Union lost, the dead and wounded might be left on the field, and this fear came to fruition. After Union troops had marched all night in retreat, several black troops were ordered back towards the battleground to help remove wounded Union soldiers who had gotten stuck on the railroad tracks on train cars. Soldiers used horses to pull the railcars since no engine was available, and then sent 300 wounded soldiers, black and white, to Beaufort, South Carolina, on the steamer Cosmopolitan. Soldiers who fell into Confederate hands suffered varying fates: Confederate troops did not massacre wounded black prisoners, but they killed a few black wounded soldiers, as men of the U.S.C.T. had feared. Confederates took approximately 70 black soldiers prisoner. They were first sent to Tallahassee. In mid-March, Confederate authorities sent the prisoners to Andersonville, where several black prisoners were placed on work details burying Union prisoners who died in the stockade’s horrid conditions.

Union troops recruited some black soldiers, took 8 cannon and several Confederate prisoners, and damaged and captured Confederate supplies, including cotton, lumber, timber, turpentine, forage, live stock, and clothing worth over $1,000,000. Florida’s government did not rejoin the Union based on Lincoln’s plans for reconstruction. Union troops still occupied Jacksonville, however, and a delegation of east-Florida Unionists attended the Republican convention in Baltimore in June 1864. Despite the Union defeat, soldiers of the United States Colored Troops again proved their grit and determination under fire as they had at previous engagements like Fort Wagner, Milliken’s Bend, and Port Hudson.

Further Reading:

The Battle of Olustee, 1864: The Final Union Attempt to Seize Florida By: Robert P. Broadwater