The Battle of Third Winchester

Krissy Dunn

Retaining control of the Shenandoah Valley was a critical task for the Confederate army throughout the Civil War. Known as the breadbasket of the Confederacy, the fertile farmlands of the Shenandoah Valley furnished a substantial amount of food to Southern soldiers and civilians. Many residents in the Valley were pacifist Quakers or Dunkers who did not join the fight. This meant that the Shenandoah Valley enjoyed continued agricultural production, unlike other areas in the South that lost labor to the war effort and the eroding slave system. Additionally, the Valley had tremendous strategic importance for the Confederate army. The Shenandoah Valley stretches approximately 165 mile from Lexington, Virginia to the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers at Harpers Ferry. Troops and supplies moving through the Valley were screened from enemy view by concealing mountain ranges. Utilizing the Valley, Confederate troops could be sent directly into positions that threatened the Federal capital at Washington.

Due to its agricultural and strategic importance, the Shenandoah Valley was a region of contention during the war and it was the scene of three major campaigns. General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson led the first Valley Campaign in 1862. In a series of six major engagements and several skirmishes that lasted from March 23 to June 9, Jackson and his 17,000 Confederates defeated a total of 64,000 Federal troops on five different occasions - one of which was the First Battle of Winchester on May 25. In addition to severely embarrassing Union officers, Jackson's Valley Campaign engaged Federal troops that otherwise could have been used to assist General George McClellan in his assault on Richmond.

In 1863, the Valley provided a major staging ground for General Robert E. Lee's Gettysburg Campaign. In June, several battles - including the Second Battle of Winchester (June 13 - 15) - cleared the Valley of the small Union presence and allowed Lee to move stealthily northward into Pennsylvania, a move that culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg. After the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, Lee used the Valley to retreat back through Virginia.

Tensions proved to be highest in the Shenandoah Valley during 1864. In May, Union General Ulysses S. Grant ordered General Franz Sigel to disrupt communications in the Valley. After a Union defeat at New Market on May 15, Grant replaced Sigel with General David Hunter. Crushing the disorganized Confederate army in the Valley, Hunter proceeded on a mission of destruction, burning the Virginia Military Institute, mills, barns, and other public buildings. Lee decided to send General Jubal Early to drive Hunter back to West Virginia, which he successfully accomplished on June 17. Seizing an opportunity, Early marched his troops northward into Maryland and Pennsylvania. After seeking retaliation for Hunter's plundering of the Valley by burning Chambersburg, Pa., Early moved to threaten Washington. Unsuccessful, Early retreated to the Shenandoah Valley, yet his outrageous maneuvers distressed the Union army.

During 1864, the upcoming presidential election greatly affected Union army strategy. Abraham Lincoln's Republican administration met a severe threat from the Democrats, led by General George McClellan. The Democrats argued that the war was not being properly fought and some even advocated allowing the Confederate states to secede in order to achieve peace. Lincoln understood that the future of his administration and the future of the country both rested in the hands of his military commanders. The war was progressing slowly in the east as Grant's Army of the Potomac was mired in a stalemate with Lee's Army of Northern Virginia around Petersburg. Grant was under political pressure from Washington to generate Union victories without taking major risks. Grant, however, felt that the continual Confederate threat in the Shenandoah Valley needed to be neutralized despite the political ramifications of possible defeat.

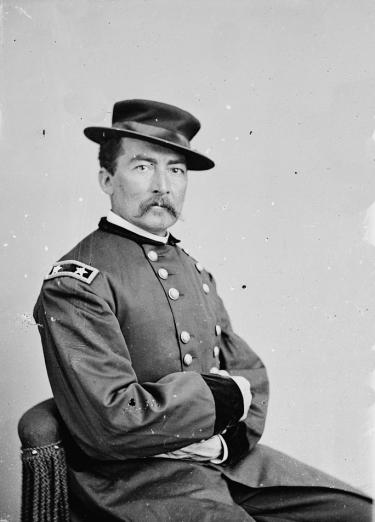

On August 6, Grant placed General Philip Sheridan in charge of the Union Sixth and Nineteenth Corps as well as two divisions of cavalry. Grant ordered Sheridan to decisively drive the Confederates out of the Valley. Initially, Sheridan moved cautiously, performing reconnaissance missions and creating espionage networks among local Unionists. His patience was rewarded on September 16. Rebecca Wright, a Quaker schoolteacher, sent Sheridan an important message delivered by Tom Laws, a freedman. Wright revealed that Early's army was "much smaller than represented." With this latest information, Sheridan met Grant in Charleston, West Virginia on the following day to discuss attacking the Confederates at Newton. Frustrated with Sheridan's inaction, Grant had already decided to meet directly with Sheridan prior to the Wright message in order to discuss battle plans and to bypass sending a message through Washington. As Grant later explained his unusual visit, "I had reason to believe that the administration was a little afraid to have a decisive battle fought at that time, for fear it might go against us and have a bad effect on the November elections." Impressed with Sheridan's plan of attack, Grant headed back to his headquarters at City Point. On September 18, Sheridan learned that Early had sent General Robert Rodes's and General John B. Gordon's divisions towards Martinsburg. Sheridan quickly changed his plan to attack the Confederates at Winchester instead of Newton.

Early had made a tremendous error in believing that Sheridan was another overly cautious Union commander. In the face of 40,000 enemy soldiers, Early had split his severely outnumbered 12,500 troops in order to move more rapidly and to appear larger. Early's forces comprised the veteran Second Corps and 4,000 cavalry. On August 6, Lee made the controversial decision to send 3,500 troops, artillery, and cavalry to Early in the Valley, instead of using them to thwart William T. Sherman's Federals in Georgia. By mid-August, however, Lee decided to recall these reinforcements due to inaction in the Valley. In her September 16 communication, Wright alerted Sheridan to this departure.

Sheridan planned to attack up the Berryville Road towards Winchester, striking first General Stephen Ramseur's division, then the forces of Generals John C. Breckinridge, Rodes, and Gordon. He hoped to quickly decimate Early's troops in detail. However, forces were already at work to undermine Sheridan's plans. Early, alerted to Grant and Sheridan's meeting, raced to re-concentrate his forces. The Third Battle of Winchester - or the Battle of Opequon, as it is sometimes called - occurred in four phases: Berryville Canyon (dawn to 11 a.m.), Red Bud Run and Middle Field (11:40 a.m. to 1 p.m.), Red Bud Run and Hackwood Farm (late afternoon), and finally the action at Fort Collier and the Star Fort (dusk).

At 1 a.m. on September 19, the morning call rang throughout the Army of the Shenandoah. By 4:30 a.m., the Union army encountered its first major hurdle of the day. After crossing Opequon Creek, the Berryville Road passes through the two-mile narrow Berryville Canyon. General Horatio Wright's Sixth Corps encountered heavy resistance when it finally exited the canyon. Additionally, Wright had ordered that the slow-moving wagon trains accompany the soldiers into the canyon. Soon, the narrow canyon became clogged with infantrymen pushing forward, wagon trains laden with supplies, and the wounded filtering back to makeshift hospitals. General William Emory, leading the Nineteenth Corps, incensed by Wright's incompetence, ignored Wright's orders and directed his men to circumvent the wagons. Soldiers of the Nineteenth Corps climbed along the sides of the hills and trampled over the wounded, seriously affecting their morale before even seeing the enemy, and delaying their arrival on the field. Early later wrote about Winchester, "When I look back to this battle, I can but attribute my escape from utter annihilation to the incapacity of my opponent." Sheridan's attempt to squeeze 20,000 troops through the narrow canyon was a tactical blunder that eliminated any possibility of destroying Early in detail.

At 11:40 a.m., cannon on the Federal line signaled for the second phase of battle to commence. Colonel Jacob Sharpe's and Brigadier General Henry Birge's Union brigades of the Nineteenth Corps advanced from the First Woods, located to the southwest of Red Bud Run. Rifle fire by Confederates in the Second Woods, 600 yards away, and pounding artillery from Major James Breathed's six cannon created a deadly crossfire. The Union line began to falter, but a drunken staff officer in Birge's brigade ordered a bayonet charge. The 31st Georgia Infantry ordered a countercharge and struggled in hand-to-hand combat with the Federals in the Second Woods. Unable to withstand the onslaught, the Georgians retreated. Seven of Lieutenant Colonel Carter Braxton's cannon, loaded with shot canister, halted the pursuing Federals. With reinforcements from two of Gordon's brigades, the Confederates countercharged and pushed the Federals back into the First Woods. During this fighting, the Federals suffered the loss of every regimental commander and 1,500 casualties. Union reinforcements attempted to charge across the Middle Field, but they never came closer than 200 yards to the Second Woods.

In tandem with the charge of the Nineteenth Corps, the Sixth Corps advanced and Ramseur's left flank crumbled under the pressure. During the Union advance, however, a gap developed between the two corps. Rodes launched a counterattack into the gap. After shouting, "Charge them, boys! Charge them!" Rodes was killed instantly from an exploding shell. A valiant countercharge by Brigadier General Emory Upton broke Rodes's division. Wright would later refer to Upton's charge as "the turning point of the conflict." Both sides were exhausted from the bloody combat and the fighting slackened around 1 p.m.

Around 12:30 in the afternoon, Sheridan ordered General George Crook's Eighth Corps to extend the Nineteenth Corps' line and to attack Early's left flank. Sometime after 3 p.m., Colonel Isaac Duval's division crossed Red Bud Run and flanked Gordon's division. In the meantime, Colonel Joseph Thoburn's division crossed the Middle Field for a frontal attack on Gordon. The two-pronged assault forced Gordon to retreat to the main body of Confederates, which had formed into an L shape.

By 5 p.m., the Confederates had formed a tight interior line position anchored at Star Fort, passing through Fort Collier, bending at Gordon's line to the west of the Second Woods, and ending near the Senseny Road. In a remarkable maneuver, two Union cavalry brigades charged against the Confederate infantry around Fort Collier. One Confederate remarked, "I never saw such a sight in my life as the tremendous force, the flying banners, sparkling bayonets, and flashing sabers moving from the north and east upon the left flank and rear of our army." Subsequently, Brigadier General George Custer's men added to the melee, breaking the Confederate right flank. The Confederate line rapidly began to crumble. Luckily for Early, Ramseur and Brigadier General Bryan Grimes organized a last stand at Mount Hebron Cemetery in order to allow the Confederates to retreat through the town of Winchester. Additionally, Colonel Thomas Munford's cavalry at the Star Fort slowed the advancing Union horsemen. Early retreated without further molestation to Fisher's Hill, where he would engage the enemy again on September 21.

Total casualties for the Union and Confederacy numbered about 9,000. The Middle Field alone accounted for a third of that number, mostly men from the Union Nineteenth Corps, which sustained forty percent casualties.

After the Third Battle of Winchester, the Confederacy's domination of the Shenandoah Valley would soon come to an end. During the 1864 Valley Campaign, the Confederacy suffered a series of four major defeats over a thirty-day period, including the devastating loss at Cedar Creek on October 19. Early was forced to leave the Valley and rejoin Lee near Petersburg. The last campaign to control the Shenandoah Valley had ended and the Union army had gained a major strategic victory. When the last Confederates marched out of Winchester after twelve hours of fighting, they had begun the final Confederate retreat from the Valley. As one veteran poetically wrote, "As the sun was slowly approaching the horizon, the last Confederate army ever in Winchester passed out."

Although the siege at Petersburg still bogged down the Army of the Potomac, General William T. Sherman's capture of Atlanta on September 2 revived Northern hopes. Union victories in Georgia and in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley breathed new life into the Lincoln administration. Northerners were now determined to see the conflict through and resoundingly voted Lincoln back into office for a second term.

Related Battles

5,020

3,610