The Third Battle of Winchester

Garry Adelman, for Hallowed Ground

WITH RICH FARMLAND THAT EARNED IT THE NAME "THE BREADBASKET OF the Confederacy" Virginia's Shenandoah Valley formed a natural travel corridor for the Union and Confederate armies in the Civil War. Winchester, Virginia and its environs at the mouth of the Valley were often frequented by these armies. In addition to changing hands dozens of times, Winchester experienced intense battles in 1862, 1863, and 1864.

1864 was an election year for the Northern states. Republican President Abraham Lincoln vied against Democratic presidential candidate (and general) George McClellan. Lincoln's largest military force, the Army of the Potomac, was mired in a siege against Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Petersburg, Virginia. In an effort to seize the initiative, Lee sent Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early and his Army of the Valley on a campaign. through the Shenandoah Valley — with the option of a possible raid on Washington, D.C. Lee hoped General Ulysses S. Grant would divide his Union army to meet the new threat.

Early's campaign was wildly successful at first. He advanced down the Valley (in the Shenandoah, traveling north was "down" while south was "up") and, overcoming a Union force at the Battle of Monocacy, reached the outskirts of Washington in mid-July. Grant responded by sending the veteran Sixth Corps from Petersburg to the Capital just in time to thwart Early's attack on the city. Confronted by superior numbers and Washington's extensive fortifications, Early retired back to the safety of the Valley.

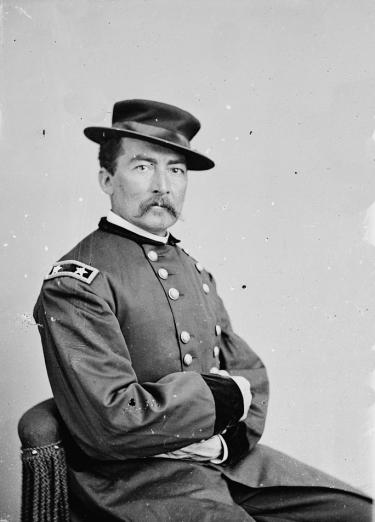

Grant had had enough of Confederates using the Valley to their advantage. He made Philip Sheridan commander of the new Army of the Shenandoah and set him the task of rendering the Valley useless to Confederates. On September 19, 1864, Early and Sheridan clashed at the Third Battle of Winchester, also called the Battle of Opequon.

At Winchester, Early's Army of the Valley consisted of four infantry divisions and two divisions of cavalry for a total of 14,000 soldiers. Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah was much larger with three infantry corps and three powerful cavalry divisions for a total of 39,000 officers and men. Both armies had ample artillery in the field but, as usual, the Yankees had more cannon, more horses, and more artillerymen.

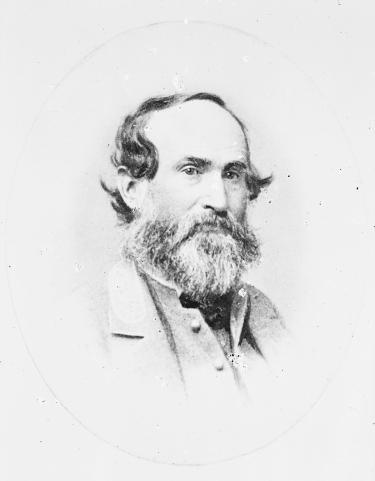

Believing that Sheridan would act like other cautious Union commanders, Early spread his smaller army over a wide front. As dawn broke on September 19, Early's forces were arrayed north from Winchester. Sheridan moved to bring his army against Major General Stephen D. Ramseur's division (that portion of Early's force at Winchester). When Early got word of the impending attack, he raced to concentrate the rest of his army at the city.

At 1 a.m. on September 19, reveille sounded throughout the Army of the Shenandoah. By 4:30 a.m., Sheridan's forces, advancing on the Berryville Pike through a narrow canyon, encountered their first hurdle of the day. Formed west of the canyon's exit, Ramseur's Confederates engaged the lead elements of Sheridan's army, slowing the passage of the rest of the Union troops. Clogged with soldiers, wagon trains, and — soon enough — Union wounded, the canyon became a choke point for Sheridan's advance.

Ramseur's men fought hard and by the time they fell back, Early's army was well on the way to concentrating at Winchester. It was nearly midday before Sheridan was ready for his assault At first, he threw his Sixth and Nineteenth Corps against the Confederate position and kept his Eighth Corps, also known as the Army of West Virginia, in reserve. He used his cavalry to probe around the flanks of the Rebels.

The Confederates were ready. By late morning, divisions under Major Generals Robert E. Rodes and John B. Gordon joined Ramseur's men. While many of Sheridan's troops were untested and under inexperienced commanders, Early's were seasoned veterans from Alabama, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, and Virginia. The veterans took position in woodlots (the eastern of which was soon to be known as the Second Woods) and amp slight ridges, guarding their flanks with artillery and cavalry.

At 11:40 a.m., the Sixth Corps, under Major General Horatio G. Wright, and the Nineteenth Corps, under Brigadier General William "Old Bricktop" Emory, advanced from a woodlot now known as the First Woods. Union Brigadier General Cuvier Grovers Second Division, Nineteenth Corps was to move across the field (now known as the Middle Field) in two lines of battle, advancing with the Sixth Corps to their left. The Sixth Corps was ordered to follow the Berryville Pike. However, unknown to Sheridan, the road veered southward taking Grover's men away from the Confederate flank and out of position. This movement, along with difficult terrain, disconnected the brigades of the Sixth and Nineteenth Corps and rendered them vulnerable to counterattack Furthermore, the Union advance was subject to intense artillery fire the entire way — especially from a battery of horse artillery beyond the Union right flank One Confederate remembered, "Our cannoneers made their battery roar, sending their death-dealing messengers with a precision and constancy that made the earth around them seem to tremble ... A more murderous fire I never witnessed than was plunged into this heterogeneous mass."

Recognizing the danger, Grover tried in vain to halt and realign his troops, but the advance would not stop until it penetrated the Confederate position. Brigadier General Henry Birge, whose brigade advanced across the Middle Field, described the situation:

"We...crossed this field under an artillery and infantry fire from the enemy in position in a belt of woods in front and extending to the right, and when within 200 yards charged with fixed bayonets at double quick. We broke his line on the entire front of the brigade and drove him through and out of the woods. As the troops entered the woods I was ordered by Gen. Grover to halt and hold that position and not to go farther into the woods, but the charge was so rapid and impetuous and the men so much excited by the sight of the enemy in fill retreat before them that it was impossible to execute the order, and the whole line pressed forward to the extreme edge of the timber."

Some of Gordon's Georgians broke and fell back — the first time they had ever done so without orders. A part of Ramseur's flank caved in as well. Union jubilation did not last long, however, as Confederate Generals Gordon and Rodes organized a swift and powerful counterattack into the disjointed Union commands. Instantly after reportedly shouting, "Charge them boys! Charge them," Rodes was killed by an exploding shell. But the attack continued, spearheaded by Brigadier General Cullen A. Battle's Alabama brigade, which plunged into a particularly weak point in the Union line Gordon's reformed men and the rest of Rodes's division joined the Alabamians and pushed the Union troops out of the woods and across the Middle Field. Seeing his men retreating and subject to intense rifle and artillery fire, "Old Bricktop" exclaimed "My God! ... This is a perfect slaughterhouse." Grover's division alone suffered 1,500 casualties in less than one hour.

The Confederates pushed on, determined to split Sheridan's army in two, and they might have done so but for reserve divisions of the Sixth and Nineteenth Corps moving up to blunt the Confederate attack. Brigadier General William Dwight, commanding the First Division, Nineteenth Corps, recalled that his men were barely in position when the Second Division "came back ... flying over the open ground between the two woods in the greatest disorder." Dwight's Division joined the action while Emory and Sheridan rallied the fleeing troops. Further to the left, the reserve division of the Sixth Corps, under Brigadier General David A. Russell, advanced to meet the attack. Russell's fate was similar to Rodes's — an exploding shell killed him instantly just as his attack got under way. As was also the case with Rodes's men, his troops advanced without him and soon slowed, then halted the onrushing Confederates who retreated to the edge of the Second Woods. For the next two hours both sides exchanged long range fire.

Realizing the armies were in a stalemate, Sheridan called for his reserves — Brigadier General George Crook's Army of West Virginia. After a hurried march, Crook's men arrived on the battlefield at roughly 1 . 30 p.m. and moved to attack on both sides of Red Bud Run. Crook's First Division, under Colonel Joseph Thoburn, moved into position in the First Woods. Crook's other division, under Colonel Isaac Duval, moved on the north side of Red Bud Run around the Confederate left flank. Crook sent word to Sheridan that he would attack immediately, and requested that the entire Union line advance in support.

Moving forward at roughly 3 o'clock in the afternoon, Duval's men charged down the steep northern bank of Red Bud Run. Duval was shot in the thigh during the charge and future President Rutherford B. Hayes assumed command of the division. The Yankees immediately came under fire from Confederate soldiers near the stately Hackwood House. As they trudged through the waist-deep water, Union troops sank into the marshy flood plain. Hayes wrote, "to stop was death. To go on was probably the same; but on we started again ... the rear and front lines and different regiments of the same line mingled together and reached the rebel side of the creek with lines and organizations broken; but all seemed inspired by the right spirit, and charged the rebel works pell-mell in the most determined manner."

As Hayes' men crossed Red Bud Run, Crook's other division, under Thoburn, advanced along with elements of the Nineteenth and Sixth Corps in support. "For thirty minutes the battle that ensued was perfectly terrific," recalled one participant, "but then the forces in our front gave way, and in an instant we were over their works, and after them with yells and shouts of victory." The combined thrust was too much for the outnumbered Southerners. The divisions of Gordon, Rodes, and Ramseur all fell back to positions closer to Winchester.

After the successful attack of Crook's Eighth Corps, it was only a matter of time before the Confederates lost the battle. As Early consolidated his lines closer and closer to Winchester, his men faced coordinated infantry attacks. Worse still, powerful Union cavalry forces fought their way south up the Valley Pike, threatening to surround Early. Although the Southerners offered stubborn resistance at Fort Collier, Star Fort, and from every fence line and barricade they could find, Early had to choose between retreat or the destruction of his army. By nightfall, the city of Winchester was in Union hands.

The Third Battle of Winchester was the bloodiest battle ever fought in the Shenandoah Valley, producing more casualties than the entire 1862 Valley Campaign. Sheridan lost 12 percent of his army with 5,000 of 39,000 soldiers killed, wounded and missing. Early suffered fewer casualties but he lost 25 percent of his army.

The dead and wounded were everywhere. One soldier of the 12th Connecticut recalled, "the Rebel dead lay thickly in the fields beyond, and were piled upon each other in the yard of a large stone mansion [Hackwood] ... A ghastly row of gray-clad corpses lay along a wall, behind which some Rebel brigade had evidently found shelter; and the fields and hillsides as far as Winchester were dotted with the fallen."

The dead were buried where they fell. Many were later moved to the nearby Winchester National Cemetery or the Stonewall Cemetery. Some 8,000 Union and Confederate soldiers from the many battles around Winchester rest in these cemeteries today. The wounded were treated in a variety of field hospitals until better facilities were established. Captain Ira B. Gardner of the 14th Maine, wounded in the arm in the Second Woods, walked back across the Middle Field to a field hospital on Red Bud Run. He soon joined some 300 wounded men at the nearby home of Charles L. Wood where his arm was amputated near the shoulder, wrapped in cloth, placed in a box, and buried in the yard. Thirty years later Gardner returned and was told that Mr. Wood had unearthed his arm and reburied it in the Winchester National Cemetery.

After the battle, Early's men retreated twenty miles south to Fisher's Hill. On September 22, they were outflanked from their position and forced to retreat again. A Confederate cavalry force was beaten at Tom's Brook, but on October 19 Early struck back one last time and nearly defeated the Army of the Shenandoah at Cedar Creek. As Union forces reeled from Early's onslaught, Sheridan organized a powerful counterattack, which reversed the tide and practically destroyed the Army of the Valley. Never again would the Confederates control or even conduct substantial operations in the Shenandoah Valley.

Related Battles

5,020

3,610