The young Continental Army soldiers who marched across the frozen ground at Princeton on the morning of Jan. 3, 1777, were comrades in a ragged fighting force cobbled together from all walks of colonial life, from New Jersey farmers to Massachusetts factory workers to the hardy longshoremen who loaded and unloaded the ships spanning New England’s storied harbors.

Alongside them, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with their white brethren, were untold numbers of African-American men — some free, and some fighting to attain freedom through self-emancipation — who shared the patriotic fervor of their fellow soldiers. As George Washington himself would say at the end of the American Revolution, this disparate group of men, “strongly disposed . . . to despise and quarrel with each other, would instantly become but one patriotic band of Brothers.” 1

Black and white soldiers together endured, Washington added, “almost every possible suffering and discouragement” with a level of perseverance that “was little short of a standing miracle.” 2

It is all but certain that blacks and whites fought side-by-side at Princeton, charging across the frozen ground of Maxwell’s Field to rout the British army in a crucial counterattack on hallowed ground — the same ground where the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) intends to build its faculty housing.

So diverse was the Continental Army at the time that a French staff officer referred to the American fighting force as “speckled”. Sadly, this would change soon after the Revolution, and 170 years would pass before America would again fight with such an integrated fighting force at the outset of the Korean War. 3

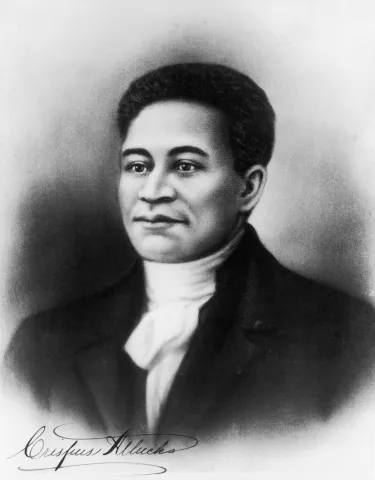

Among the first Americans to take up the cause of freedom were the dockworkers of Boston, whose ranks included men of many colors. Crispus Attucks, a black Bostonian employed in the maritime industries, was the first patriot to die during our country’s foundational conflict, shot down with others at the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770.

After the Revolution began, New England regiments enlisted African Americans as fighters. The most conspicuous example was the 14th Continental regiment organized by John Glover, which was made up of New England fishermen, including many of color.4 The 16th Continental regiment also counted black soldiers in its ranks.5 Likewise, African Americans almost certainly served in the 11th Continental regiment from Rhode Island. Later in the war, the regiment was transformed into the 1st Rhode Island regiment — and became what is considered the first all-black regiment in American history.

The 14th Continentals manned the boats famously used by Washington to cross the Delaware River on Christmas Day, 1776, and African-American soldiers fought in Washington’s spectacular victory at Trenton the following day.

Determining exactly who fought at Princeton is difficult, as with the end of 1776 came the end of enlistments for many soldiers, who would then have been free to abandon the many hardships of the Continental Army and return home.

After pleas from their officers — including Washington himself — to stay, many agreed to do so for six more weeks. Washington considered this a personal favor, and did not officially re-enlist the men, leaving no official record of who departed and who remained to fight at Princeton.6

But many New Englanders heeded Washington’s call, including almost all of the 11th Continentals. And at least two black Marines — “Isaac Walker” and “Orange” — are listed on muster rolls for Dec. 1, 1776 through April 1, 1777, in a unit that participated in the Battle of Princeton.7

Washington was on the verge of losing the battle after the left side of his line buckled under a British assault. But the arrival of more American regiments, including the 11th Continentals, set the stage for the counterattack that Washington personally led from the saddle of a battle-nervous white horse. The victory helped turn the tide of the Revolution.8

African-American participation in the war, to be sure, was fraught with contradictions and uncertainties rooted in racism. Washington and the Continental Congress, for example, initially considered blacks unfit for military service. The need for more soldiers soon eliminated those objections. Promised their freedom in exchange for their enlistment, hundreds of enslaved men fought on both sides, only to remain in bondage after the war.9

But African-American service in the Revolution was far more extensive than most people realize, with black soldiers and sailors numbering upwards of 5,000. A Continental Army roster now among Washington’s papers lists 755 black soldiers in 15 different brigades of Washington’s main force at White Plains, N.Y., in the summer of 1778.10

Three years later, Baron Ludwig von Closen, a foreign officer serving with the French forces assisting the Continental Army, wrote of how highly he regarded American soldiers — a quarter of whom, he said, were black. “I admire the American troops tremendously!” von Closen exclaimed. “It is incredible that soldiers composed of men and every age, even children of 15, of whites and blacks, almost naked, unpaid, and rather poorly fed, can march so well and withstand fire so steadfastly.”

References:

1 George Washington, “Farewell Orders to Continental Army,” Nov. 2, 1783. [link]

2 Ibid.

3 Lloyd Dobyns, “Fighting. . . Maybe for Freedom, but probably not,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Autumn 2007. [link]

4 David Hackett Fischer, “Washington’s Crossing,” (Oxford University Press), page 22

5 David Hackett Fischer, “Washington’s Crossing,” (Oxford University Press), page 252

6 David Hackett Fischer, “Washington’s Crossing,” (Oxford University Press), page 272-273

7 Michael Lee Lanning, “African Americans in the Revolutionary War,” (Citadel Press, 2005), page 96. [link]

8 David Hackett Fischer, “Washington’s Crossing,” (Oxford University Press), page 335-338

9 John U. Rees, “’They were good soldiers.’ African-Americans Serving in the Continental Army.” [link]

10 Ibid.

Related Battles

75

270