In the Bloody Cornfield, Pvt. Howard Left Behind a Widow and Three Children

Ancestry and Fold3 have been helping people understand their ancestors and why they fought for causes large and small for decades. Now, Ancestry and Fold3 are joining forces with the American Battlefield Trust, so that you can find the veterans in your family's past and understand their stories and the impact on the generations that followed. You can learn more at https: www.fold3.com/projectregiment.

In addition to this recurring Hallowed Ground column, this partnership has resulted in an exclusive discount for Trust members to subscribe to Ancestry and Fold3! Check your email for this exclusive offer.

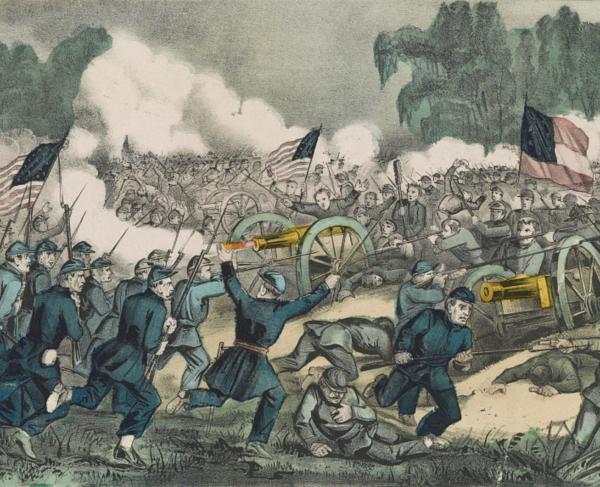

The Battle of Antietam still looms large in the American consciousness. It was the Union victory upon which President Abraham Lincoln pinned his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The pictures captured by Alexander Gardner and his team of photographers changed how Americans looked at war, bringing home its tragedy with images of the dead on the battlefield. The vast number of casualties made medical teams rethink procedures for triage and battlefield surgery in ways that echo into the 21st century. But for the families and loved ones of the more than 22,000 men killed, wounded or captured at Antietam, it was a personal experience. And their lives were never the same.

The S.G. Elliott Burial Map for Antietam records more than 50 specific field burials by name. These are the stories of some of those individuals.

The Irish Immigrant

Miles Casey and his wife Jane were both born in Ireland. She was a widow with four children when they married and settled in Rochester, N.Y. They had one son together, also named Miles, who was about two when his father left for the war. No stranger to war, having fought in Crimea for the British Army, Casey volunteered to fight for his new country, and his fellow soldiers honored him by making him a color bearer— one who carries the flag.

Casey enlisted in Company K of the 108th New York volunteers on August 8, 1862. A little more than a month later, his regiment saw in its first battle at Charleston, W.V. Four days later, when the regiment took fire from Confederates defending a Sunken Road near Sharpsburg, Md., Casey took a bullet in the left leg.

Col. Oliver Hazard Palmer of the 108th wrote to his cousin: “The action commenced about 7½ o’clock in the morning. My command remained in line and continued in position – firing with great rapidity and energy in the face of deadly fire of the enemy, where were stationed in the cornfield and rifle-pits, not more than twenty or thirty rods distant, until about half past 12 o’clock in the afternoon.

During the action a charge was made up on the rifle pits, and my command took 159 rebel privates, and non-commissioned officers, three rebel captains and six rebel lieutenants, also one stand of the Reg’t Colors of the 14th North Carolina Reg’t. These colors were taken by Henry Niles, in Co. K.”

The severely wounded Casey was found by his fellow soldiers later in a frame house near the Bloody Lane. A bullet passed within two feet of Casey as his comrades checked on him, but he was not concerned, reporting: “I’m used to them.” Carried a few miles to a hospital in the rear, Casey’s left leg was amputated, but it was not enough to save him, and he died the day of the battle. As the Sisters of Mercy were helping to bury him, Maj. Gen. George McClellan and his staff rode by, and they waited as his remains were lowered. The gesture of respect was cold comfort to Jane, twice a widow with five children to raise alone.

The Planter’s Son

Richard L. Nobles was the son of Jesse Nobles, a planter in Pitt County, N.C., who owned many acres of land and 34 enslaved people to work them. Nobles came from a small family; his mother and older sister had died a few years before the war, leaving only him and his younger sister living with his father. Nobles enlisted in Company A of the 27th North Carolina Infantry as a private on August 19, 1861. They first saw real action on March 12, 1862, at New Bern in Craven County, N.C., where Nobles’s conduct supported his election to lieutenant the following month. The 27th saw more fighting in the passes of South Mountain in the summer of 1862, as the Confederate army moved north into Maryland.

Assigned to Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s right wing, in Brig. Gen. James Walker’s division, the 27th and the other regiments of Col. Van Manning’s brigade participated in some of the early fighting at the Battle of Antietam. Around 9:30 a.m., the 27th North Carolina and 3rd Arkansas were sent to plug the gap between the West Woods and the Sunken Road. They continued driving forward until Union troops began an endless barrage, wounding Manning and causing the brigade to retreat.

The record does not definitively state that this is where the 22-year-old Nobles was shot in the leg, but it is likely. In the confusion of battle, his fellow soldiers believed that he had been captured and taken prisoner. And he may have been a prisoner for a few hours, but that status changed swiftly. Service records tell us that Nobles died at the Otho J. Smith Farm, which is supported by the location of his grave on S.G. Elliot’s map.

The Mystery Casualty: Wounded, Deserted or Dead?

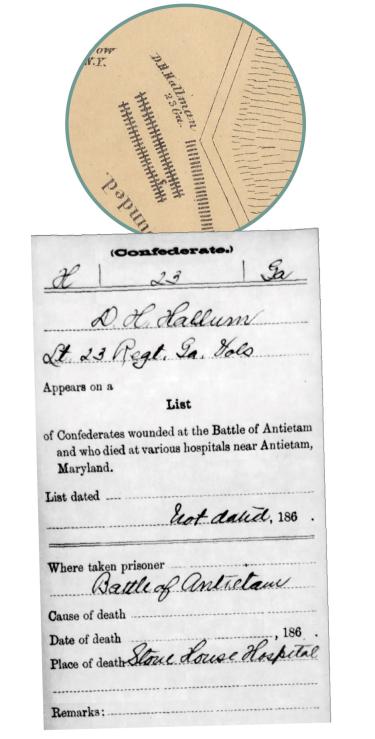

Vincent Hallum, the son of a miller, grew up in Yahoola, Ga. He married Sara Bradley around 1855, and she soon bore him three children — all under the age of four when he enlisted in Company D, 23rd Georgia Infantry on August 31, 1861. The 23rd began its Civil War experience with the Siege of Yorktown. They fought at Williamsburg, Seven Pines, Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill. As the Confederate army moved into Maryland, Hallum was elected second lieutenant on August 24, 1862.

On September 14, the 23rd saw action in the Battle of South Mountain, holding Turner’s Gap alongside the 27th Georgia. They were met with stiff resistance from the 7th Wisconsin and other Union troops, who had superior numbers, but the Confederates delivered a “terrific musketry … this gave them a sudden check … they made still another effort to advance, but were kept back by the steady fire of our men.” Col. Alfred H. Colquitt, commanding the brigade, claimed his men never yielded an inch of ground, but they exhausted their ammunition and retreated from their position.

Hallum survived the day and was with the 23rd at Antietam. At some point during the fighting on September 17, he suffered a compound fracture in the right leg, and the wound swiftly proved mortal. Most likely, given that Elliott records a burial for a D.H. Hallum west of the Smoketown Road, he fell around 8:15 a.m., when Colquitt’s men were sent into Miller’s Cornfield to relieve the men in Col. Rosewell Ripley’s brigade, who had fought to exhaustion.

Hallum’s service records specify that he died in the Stone House hospital; other records say that he was killed in battle. Given that records detail his leg injury, the hospital scenario is likely. His wife, Sarah, filed a claim in January 1863 and received $138.69 for Hallum’s service and death.

In most cases, the story would end there. But Hallum’s service record isn’t so straightforward. On September 25, 1862, a V.H. Hallum, second lieutenant of Company D, 23rd Georgia Infantry, was paroled by the Union army in the aftermath of the Battle of Antietam, pledging to not take up arms against the United States once released. If Hallum was buried on the field, who was paroled under his name? Did someone impersonate him, or did the real man use the chaos of battle to disappear? Hallum’s family believed he had perished, and was able to convince the Confederate government this was true. His widow Sarah married Thomas Langford, a veteran of the 32nd Georgia Infantry, and remained in Georgia.

The Tammany Regiment

In dozens of other instances, the Elliott Map identifies burial groups — masses of crosses or tick marks driving home the battle’s enormous human cost — by regiment, confirming for historians where a unit was engaged.

One of these large groups is located in the West Woods, identified as the dead of the 42nd New York, which suffered a brutal day on September 17, 1862: Of the 345 men who entered the fight, 41 were killed, 127 were wounded and 13 were reported missing in action.

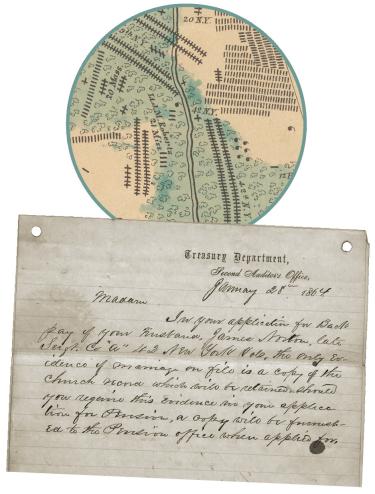

But who were the men of the 42nd? Many were immigrants who had left Ireland during the potato famine. John Duffy was a day laborer with a wife and two young sons when he joined at age 42. Timothy McEvoy, 35, another immigrant, left his wife and three young children to join up. James Norton was working at a foundry when he left his young family to join the Union cause. All three lost their lives on the field at Antietam, leaving their families with very little.

Originally known as the Jackson Guards, they renamed themselves the Tammany Regiment. Many of the enlistees came from Long Island and the neighboring area, except for Company H, which was made up of men from Boston — they chose to fight under the New York banner, as Massachusetts was not raising regiments at that point in the summer of 1861.

By the time they reached Antietam, the men of the 42nd had seen their fair share of battles, including Ball’s Bluff, Seven Pines and Chantilly. When they reached the battlefield, they were part of Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick’s Division. They approached the East Woods around 8:45 a.m., and crossed the Cornfield and Hagerstown Pike north of Dunker Church before proceeding into the West Woods. They stopped to reform their ranks, and their commanders mistakenly identified nearby troops as friendly. They were quickly disabused of that notion when the rebels launched volley after volley at them, a wall of fire what brigade commander Brig. Gen. Napoleon J.T. Dana called “the most terrific I ever witnessed.” Dana’s command saw about 900 casualties during the morning’s intense action, including a severe wound for the brigade’s leader.

Sons of Stoughton: Company I, 12th Massachusetts Infantry

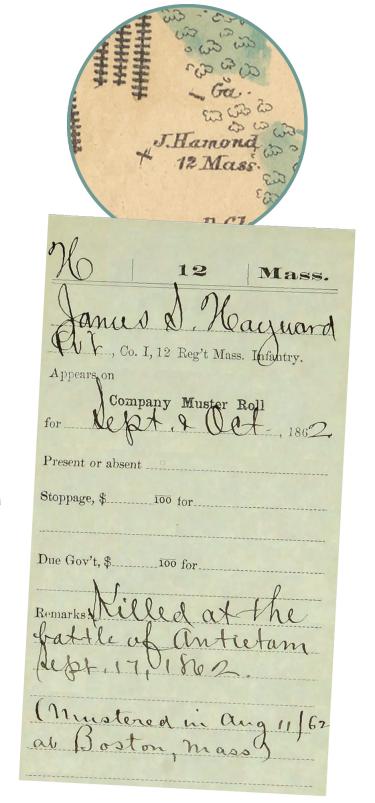

In 1860, Stoughton, Mass., was town of about 4,200 people made up of approximately 1,300 families. And on June 26, 1861, 46 of Stoughton’s young men volunteered and joined the 12th Massachusetts Infantry Company I, which was later designated the color company.

The regiment was originally commanded by Fletcher Webster, son of U.S. Se. Daniel Webster, until he was killed in action at Second Manassas. After reorganization, the 12th was made part of Brig. Gen. George Hartstuff’s brigade. The regiment had fought in multiple battles before Antietam, including Ball’s Bluff, Gaines’ Mill and Cedar Mountain. In May 1862, the men enjoyed a brief trip home, as reported in the Fall River Daily Evening News: “They brought away with them numerous relics of secessia, and declare themselves fully convinced that Virginia — the scene of their labors — is a thoroughly cursed country. They were encamped near the spot where John Brown was hung and relished the idea that a spot so memorable should be overrun by Massachusetts men.”

After returning to action, they emerged from the fighting at South Mountain on September 14 relatively unscathed. But on September 17, the 12th Massachusetts suffered the highest percentage of casualties among Union troops at Antietam: more than two-thirds of its strength reported killed wounded, captured or missing. These were the victims of fighting in Miller’s Cornfield, or the Bloody Cornfield, and of the 334 men who started the battle, 74 of whom died on the battlefield or not long after.

From The Citizen Soldier, we find this account: “Early Monday morning we move down the west side of the mountain … tired, ragged and dirty. We capture a picket-line in the darkness, among them a captain of the 1st Texas, a lawyer of Austin … after this little affair is over, we lie down on our arms in a cornfield and this captain … tells us to our surprise that the whole rebel army is in front of us.

“Company I had the colors. Forward in the line of the battle: the fogs lifts, and in an instant a rebel battery on our right opens on us, with rather poor range at first, but they soon get it closer; and by command down we go, our faces in the dust. Onward and upward. Through the field to the heavy fence that bordered the memorable cornfield, where later in the day, the dead were literally piled up.

“Onward into the cornfield. Ah, there they are! A long line of graybacks is seen filing out on our left and front. ‘Give it to them, boys!’ Still those dreadful shot and shell plough through Company I.”

Company I’s Capt. John Ripley of Stoughton was wounded that day. He eventually returned to duty, only to be mortally wounded at Fredericksburg. Lt. Warren Thompson and Henry W. Ripley were both taken prisoner. Thompson was released, only to be captured again at Gettysburg, but later was able to rejoin his regiment a second time.

On the S.G. Elliot Map, only a J. Hammond is marked with a little cross. He is most likely James S. Hayward, a boot maker from Stoughton, who left behind a wife, two daughters and one-year-old son. Unmarked on the map, but probably buried close by, are James Austin, Harvey Darling, Randall Holbrook and Charles Johnson. Six other men from Company I were wounded, George Henry mortally so.

In many ways the Civil War was fought by communities, especially since companies were raised in particular towns and neighborhoods. The Battle of Antietam left the little town of Stoughton, more than 400 miles away, forever changed.