Book: What the Yankees Did to Us

Stephen Davis's recent book, What the Yankees Did to Us: Sherman's Bombardment and Wrecking of Atlanta explores one of the saddest chapters of the Civil War: the end of the Atlanta campaign and the devastation of the City of Atlanta. The Trust recently had a chance to talk with Davis about his work.

Civil War Trust: First of all, this is a pretty provocative title. How did you come up with it?

Stephen Davis: A product of much rumination. One of the benefits of taking a long time to write a book is that an author can reflect on just what it is he wishes to say. I think that telegraphing one’s intent to prospective readers is appreciated by them (and by the publisher, who tends to like catchy titles).

More fundamentally, I'm an Atlantan, and when I speak of "us" I really mean the physical city of 1864 as much as the people who lived in it. Our city’s seal continues to show a phoenix rising from the fires of the Civil War. The Yankees’ devastation is thus a permanent part of our city’s history. I wanted to convey that we down here still think about this, and that the story still matters.

Your work really focuses on the civilian experience of the Atlanta Campaign. How did the residents of Atlanta deal with the prospect of war coming to their doorstep?

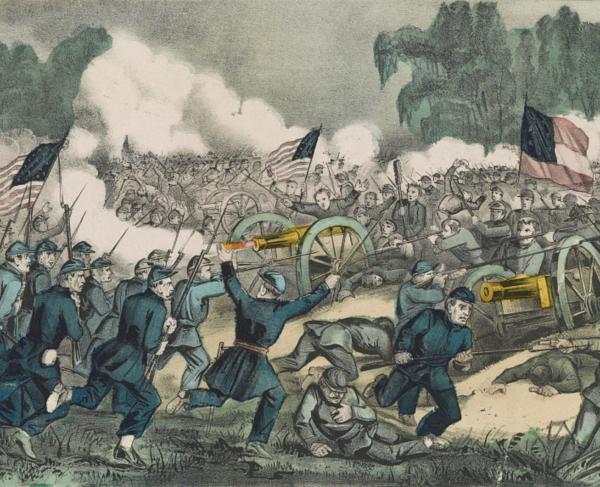

SD: Most Southerners in 1861 did not foresee the hard hand of war visiting them, and we here in Georgia didn’t either. No one would have predicted that Confederate engineers would have to construct a perimeter of fortifications around Atlanta to keep the Yankees out, much less that our city would someday fall to them.

What was Atlanta like at the time of the Civil War?

SD: A "city on the make" is the way I term it in my work. With a population of 10,000, it was the third largest in Georgia, and not yet the capital. But it boasted industry, rail connections, and enterprise, such that some civic leaders even pitched it as a possible site for the Confederate capital.

In your view, when did the destruction of Atlanta begin?

SD: I cite different stages of property damage. Confederates themselves cleared forests and leveled buildings in constructing their fortified lines in the city’s suburbs. Work began in the summer of 1863; property owners had to be paid by the government in compensation.

Then came the Federal bombardment of July 20-August 25, 1864. The Yankees' fortified lines outside Atlanta also ruined buildings. They burned the Troup Hurt house in late July when a shift in their position left the house out in no-man's-land. They cleared away huts and outbuildings behind their lines too for firewood; Augustus Hurt, Troup's brother, was angry to his dying day that his house had been dismantled behind Federal lines during their semi-siege.

Confederates' detonation of the artillery train on the night of the evacuation (September 1, 1864) created explosions that left the surrounding area a virtual moonscape, as shown in George Barnard's famous photograph. Some Federals alleged that the retreating Rebels also burned some structures in the city containing ordnance or supplies.

During the occupation, September 2-November 16, after Sherman expelled most of the populace, soldiers tore down buildings for the wood to make their shanties. They weren't shy about this; Frank Leslie’s carried a front-page illustration of soldiers tearing down a house and loading its doors on a wagon. Sherman's Chief Engineer, Captain Orlando Poe, oversaw the tearing down of more buildings during October when Sherman ordered him to dig a new, shorter, fortified line well within the city limits. This included a three-story girls’ school, which came down on October 23.

A chief cause of damage was the intentional destruction by Sherman's engineers and pioneers of railroad roundhouses, factory buildings, and other structures in the days before they left for Savannah. What has thrown me all of these years is why they wanted to burn the unoffending storefront district along Whitehall and Peachtree Streets. I found the answer: several officers record that Sherman wanted everything brick in the city to be leveled.

Finally, of course, were the Union soldiers’ unauthorized fires of November 11-15. When they saw the engineers knocking down the railroad buildings, then setting fire to the rubble, the men joined in by setting fires of their own.

How much of Atlanta was destroyed?

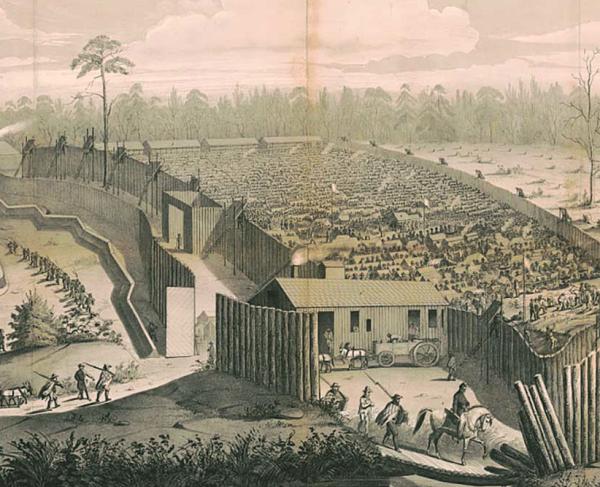

SD: We'll never know with certainty. The Yankees, of course, lowballed their estimates: 25% (Major Henry Hitchcock of Sherman's staff); 37% (Captain Poe, though I don't know how he got that figure). For Confederates, the highest estimate comes from Georgia militia general William P. Howard, who told Governor Joe Brown that 3,200 houses inside the city limits were gone. Adding suburban homes, Howard came up with a figure that equates to 11/12, or 92% of the city gone.

I tend to think Howard’s number is too high, especially as I found several newspaper reports from eyewitnesses who described Atlanta after Sherman left. They seemed to confine the burned areas to major thoroughfares such as Marietta Street, which would have been the main route used by Union soldiers marching into the city from the northwest. One thing is clear: percentages may merely be gradations of hell. The war did a number on Atlanta.

Was Sherman's decision to destroy civilian property merely an act of cruelty or one of military necessity? Was it both?

SD: Both, in ways that I bet even Sherman couldn’t have explained.

I have cats, and we feline-lovers like to joke about figuring out how the cat brain works. Same thing with Cump Sherman. Military ethicists are still pondering the moral dimensions of his theory of hard war, which he never expounded upon (though we have some of his pithy quotes). Sometimes I take the position that by strict standards he violated the laws and usages of war, but that’s almost beside the point. My feeling is that he associated the wrecking of Rebels’ property as just retribution for their having started a war that wrecked the peace and order of the republic (recall John Marszalek’s biography, A Soldier’s Passion for Order). I cite Major Hitchcock’s recording of his conversation with Sherman on November 13 as they watched the burning of houses in Marietta, Georgia; Sherman said, "I say Jeff. Davis burnt them." Even my cats wouldn’t come up with such tortuous, convoluted reasoning!

Couldn't the extent to which private property was stolen or destroyed be attributed to Union soldiers taking matters into their own hands? How much of a role did Sherman himself play in the wrecking of Atlanta?

SD: I say that Sherman never ordered his soldiers to set fires in the city because he didn’t have to. Earlier in February '64, he had led the Fifteenth Corps across the Mississippi from Vicksburg to Meridian, tearing things up and burning things down, so Sherman’s boys knew that this was what the general wanted. Moreover, during the second week of November, the Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Seventeenth Corps were marching with Sherman from northwest Georgia back to Atlanta, from whence they would begin their march to the sea. Along the way, they burned parts of Rome, Cartersville, Marietta, and other towns, and they saw Sherman look the other way. When they began to march into Atlanta, they said that the pioneers were having all the fun (an actual quote), and they started setting their own fires.

One of the points I make is how Sherman changed his mind on who would do the work. The late Professor Tom Dyer found Col. William Cogswell's papers at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, and from them we know that at first Sherman assigned the wrecking and burning to the three regiments of provost guards in the city. But then (according to Major Hitchcock) he changed his mind and assigned the work to Captain Poe's engineers; they knew how to knock things down without using fire until the last moment—Sherman’s orders. My point is that Sherman didn't care if Atlanta burned; he just didn’t want the burning to be carried out by undisciplined, riotous (and possibly drunken) soldiers running loose in the city before he intended to set out for the sea.

With all the devastation in Atlanta, one would think it would be difficult to get Southerners’ perspective on how events transpired. How were you able to reconstruct the civilian experience in such detail?

SD: I just kept finding sources with more information, and my publisher kindly and generously let me keep adding it to my text. (My thanks go to Dr. Marc Jolley and Mercer University Press for a great partnership.) Example: we were working on the penultimate set of proofs when I found at Emory the manuscript diary of Lt. William Armor, Brig. Gen. John Geary’s aide. From it I learned when Geary moved into Edward Rawson's house, "The Terraces," which he had been eyeing as his possible quarters since he entered the city. My publisher let me add this detail—the kind I like to think adds richness to the story of What the Yankees Did to Us.

I used Confederate newspapers a lot, too, in a way that I think contributes to the literature. The Atlanta/Macon Intelligencer and Memphis/Atlanta Appeal carried daily columns on "the city," especially on the damage being done by Sherman's shells. I plumbed them extensively, in the belief that our (Atlanta's) story had not been told as fully as possible because previous writers hadn't worked at extracting the papers’ valuable material.

Is there anything left of Civil War Atlanta? What can visitors see today?

SD: The city, of course, has sprawled over the wartime earthworks and suburban battlefields. On my tours of the Peachtree Creek "battlefield," our bus literally whizzes by roadside historical markers, though topographical features such as "the Ravine" still exist.

On the other hand, there are a few landmarks important to note. Architecturally, the antebellum home of Capt. Lemuel P. Grant, who supervised the city's fortification, is still preserved for tours and visits. Fort Walker in Grant Park (Lemuel, not Ulysses) is the best known extant earthwork inside the perimeter highway, but there's a well-preserved Confederate artillery redoubt off of Cascade Road. And downtown, in Underground Atlanta, stands the iron lamppost which, during the bombardment, was struck by a Northern shell. A fragment hit Solomon Luckie, a free African-American barber, who died despite medical care. I think it is ironic that Atlanta's best documented bombardment victim was an African-American.

Is there one story from the book that you’re particularly interested in?

SD: The Willis bombproof. In the early 1930s Wilbur Kurtz—the guardian angel of Atlanta’s Civil War past—was reading Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox's memoir and learned that near Cox's line there had been a big underground bomb shelter on the property of one Joseph Willis. Kurtz got in his car, drove out to Cascade Heights, and started asking around about the Willis property. Lo and behold, he met Elizabeth Herren, Willis’ daughter. She had been born just after the war, but remembered well her parents talking about the bombproof and how it sheltered not only her family, but neighbors’. Mrs. Herren showed Kurtz where it had been dug and told him how it had been built. She even remembered the names of 21 people who had regularly sought refuge there. Kurtz drew the bombproof based on Cox’s description and Mrs. Herren’s recollection, then wrote a great article about it for the newspaper. And thank heavens he did. A few months later, Mrs. Herren, 65 years of age, was kicked by a cow and died of surgical complications. If it had not been for Wilbur Kurtz, the story of the Willis bombproof would have been lost for all time!

(By the way, I think I'm the first student to put this story into the literature of wartime Atlanta. I thank the Atlanta History Center for helping me print Kurtz’s drawing, too.)

What is the one thing you hope readers will take away from your book?

SD: I gave a talk on my work this past summer at Gettysburg, and afterward a very cordial couple asked me this question: "We're from New York. What would you have us take away from your talk today, and share with our friends and neighbors?" I recalled with them Robert Penn Warren’s observation that the Civil War is, for many Americans, our only "felt" history. I told them that I am married to a wonderful woman born and raised in New York, who always tells me that when she was taught American history in school, they never thought about the Civil War up there.

"Well," I said, "please tell your friends and neighbors that they might not think about the war up there, but down where I come from, we think about it every day."

Buy the Book: "What the Yankees Did To Us" is available from our Civil War Trust-Amazon Bookstore

Stephen Davis of Atlanta earned a PhD in American Studies, an MA from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and a BA from Emory University. His hobby since the fourth grade has been the Civil War, on which he has written more than 100 articles. For over 20 years, he served as book review editor for Blue & Gray Magazine. His book, Atlanta Will Fall: Sherman, Joe Johnston, and the Yankee Heavy Battalions, was published in 2001.