A Brief Overview of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 brought the United States onto the world's stage in a conflict that ranged throughout the American Northeast, Midwest, and Southeast, into Canada, and onto the high seas and Great Lakes.

The United States went to war against Great Britain. The British were already waging a global war against France, one which had been raging since 1793. Canada, then under British rule, became the primary battleground between the young republic and the old empire.

The seeds of war were sown in many places. Since their war had broken out, Britain and France had both tried to restrict international trade. The United States was put in an awkward position, unable to trade with either world power without incurring the wrath of the other. In response, Congress passed a series of non-importation acts and embargos, each time trying to force the European powers to feel the sting of losing access to American markets. Europe was largely unmoved, and the United States fell into an economic depression.

During this time, the British were also doing several other things that Americans considered to be insulting. They rejected America's claim to neutrality in the global war, effectively dismissing the former colony's national legitimacy. They stopped American ships at sea and "impressed" American sailors—forcibly recruiting them into the Royal Navy on the spot. They also armed Native American tribes that preyed on frontier settlers.

From 1783-1812, the British Parliament issued twelve "Orders in Council," which declared that any merchant ship bound for a French port was subject to search and seizure. Because the United States traded regularly with France, the Orders put a heavy strain on Anglo-American relations. The Orders in Council of 1807 led to the ill-conceived Embargo Act, signed by Thomas Jefferson, which closed all American ports to international trade and plunged the American economy into a depression. In many ways the brewing war would be for freedom of the seas. A century later, the United States would once more go to war for the same cause, this time against Imperial Germany.

When James Madison was elected to the presidency in 1808, he instructed Congress to prepare for war with Britain. On June 18, 1812, buoyed by the arrival of "war hawk" representatives, the United States formally declared war for the first time in the nation's history. Citizens in the Northeast opposed the idea, but many others were enthusiastic about the nation's "Second War of Independence" from British oppression.

Ironically, the British Parliament was already planning to repeal its trade restrictions. By the time the ship carrying news of the declaration of war reached Great Britain, almost a month and a half after war had been declared, the restrictions had been repealed. The British, however, after hearing of the declaration, chose to wait and see how the Americans would react to the repeal. The Americans, after hearing of the repeal, were still unsure how Great Britain would react to the declaration of war. Thus, although one of the main causes for war had vanished, fighting began anyway.

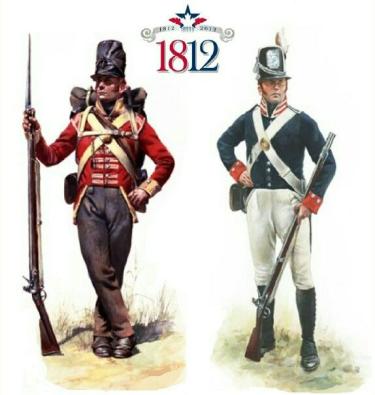

The poorly trained U.S. army, numbering roughly 6,700 men, now faced an experienced adversary fielding over 240,000 soldiers spread across the globe. America's military fleet was large, but Britain's was much larger.

The United States entered the war seeking to secure commercial rights and uphold national honor. The American strategy was to quickly bring Great Britain to the negotiating table on these issues by invading Canada. Captured Canadian territory could be used as a powerful bargaining chip against the crown.

The invasion of Canada, which began in the summer of 1812, ended in disaster. By the end of the year 1812, American forces had been routed at the Battle of Queenston Heights on the Niagara River, a thrust into modern-day Québec had been turned back after advancing fewer than a dozen miles, and Detroit had been surrendered to the Canadians. Meanwhile, British-allied Native Americans continued their raids in Indiana and Illinois, massacring many settlers.

The Americans performed better at sea. Although the British were able to set a semi-tight blockade along the Atlantic seaboard, American ships won several battles against British warships and captured a number of British trade vessels. The Americans continued to ably combat the formidable Royal Navy throughout the war.

American fortunes fared little better through most of 1813. An attempt to retake Detroit failed near Frenchtown, Michigan, though the resulting massacre of American prisoners at the hands of Native Americans on January 23, 1813, inspired Kentucky soldiers to enlist, heeding the new rally cry "Remember the River Raisin!" Continued attempts at capturing Canada resulted in only temporary footholds at York and Fort George along the Niagara front. The Battles of Chateauguay and Crysler's Farm again prevented American forces from advancing on Montréal.

The only considerable American successes occurred in September, with Oliver Hazard Perry winning a major naval battle on Lake Erie, and in October when the Tecumseh's Confederacy of northwestern Native American tribes was crushed at the Battle of the Thames.

Towards the end of 1813, a war among the Creek nations erupted in the Southeast between factions influenced by Tecumseh's nativism and those who sought to adopt white culture. The opposition faction, known as the Red Sticks, attacked American outposts including Fort Mims, Alabama.

Andrew Jackson organized a force of militia over the winter of 1813-1814 and defeated the Red Sticks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend on May 24, 1814. Through the Treaty of Fort Jackson, he forced both sides of the Creek Nation, even those allied to him, to cede nearly 23 million acres of what would become Alabama and portions of Georgia.

In 1814, the newly promoted Brigadier General Winfield Scott implemented a plan of strict drill for American troops on the Canadian border. They advanced into Upper Canada and scored a decisive victory at the Battle of Chippawa on July 5, 1814, but were forced to withdraw weeks later after the bloody Battle of Lundy’s Lane near Niagara Falls.

In April, a brief peace broke out in Europe as Napoleon was forced into his first exile. Great Britain was able to shift more resources to the North American theater. The tone of the war changed as Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin described, "We should have to fight hereafter not for 'free Trade and sailors rights,' not for the Conquest of the Canadas, but for our national existence." At the same time, however, the British began the process of repealing their policies of impressment and trade strangulation.

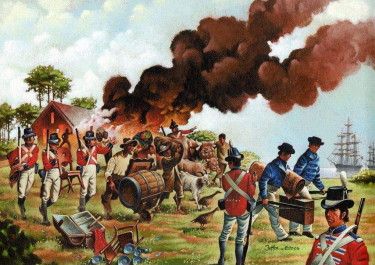

On August 19, 1814, an expeditionary force of 4,500 hardened British veterans under the command of General Robert Ross landed at Benedict, Maryland and began a lightning campaign. After routing Maryland militia at the Battle of Bladensburg, Ross's men captured and burned the public buildings in Washington, D.C., including the White House. That month, peace negotiations began in the European city of Ghent.

On September 12, Ross and his force attempted to take Baltimore with the support of the Royal Navy. Maryland militia held off the land assault at the Battle of North Point, killing Ross. Fort McHenry repulsed the British ships in a 25-hour battle that inspired the American national anthem. The British abandoned their designs on Baltimore, but soon launched another invasion of the Gulf Coast.

On December 24, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent was signed and peace was agreed upon. Word was again slow to travel, however, and on January 8, 1815, Andrew Jackson engaged a British force outside of New Orleans, resulting in a stunning but ultimately pointless victory. On February 18, 1815, the Treaty of Ghent was officially ratified by President Madison, and the nation ended the War of 1812 with "less a shout of triumph than a sigh of relief." 15,000 Americans died during the war.

The terms of the peace were status quo antebellum, "the way things were before the war." All land reverted back to its original owners. British agents stopped supporting Native American raiders. The British trade restrictions and impressment policies had already been repealed. America had fought its old master to an honorable draw, and Britain had avoided disaster in North America while defeating the French in Europe. Canada gained a proud military heritage. The War of 1812 is somewhat paradoxical in that relations between the warring factions generally improved after the war.

The Native Americans, however, were the worst losers of the war. Many of them had fought in the hopes that Great Britain would insist upon a recognized Native nation in North America as part of the peace, but the British quickly abandoned the claim during the peace negotiations. Additionally, without British money and weaponry, the Native Americans lost the ability to defend their lands and attack U.S. settlements, increasing the rate of U.S. expansion.

In America, the war was followed by a half-decade now called the "Era of Good Feelings." The coming of world peace spurred an economic revival, and the collapse of the Federalist Party, which had bitterly opposed the war, removed much of the rancor from American politics. However, this was only an era, not an eternity. Having won its "second independence," the United States would soon have to confront its first sin—slavery.

Further Reading

- The War of 1812 in the Age of Napoleon By: Jeremy Black

- The Burning of the White House: James and Dolley Madison and the War of 1812 By: Jane Hampton Cook

- The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict By: Donald R. Hickey

- Privateering: Patriots and Profits in the War of 1812 By: Faye M. Kert

- The Naval War of 1812: A Complete History By: Theodore Roosevelt

- The Slaves' Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812 By: Gene Allen Smith

- The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies By: Alan Taylor

Related Battles

1,105

128

123

440

853

878

200

250

62

2,034