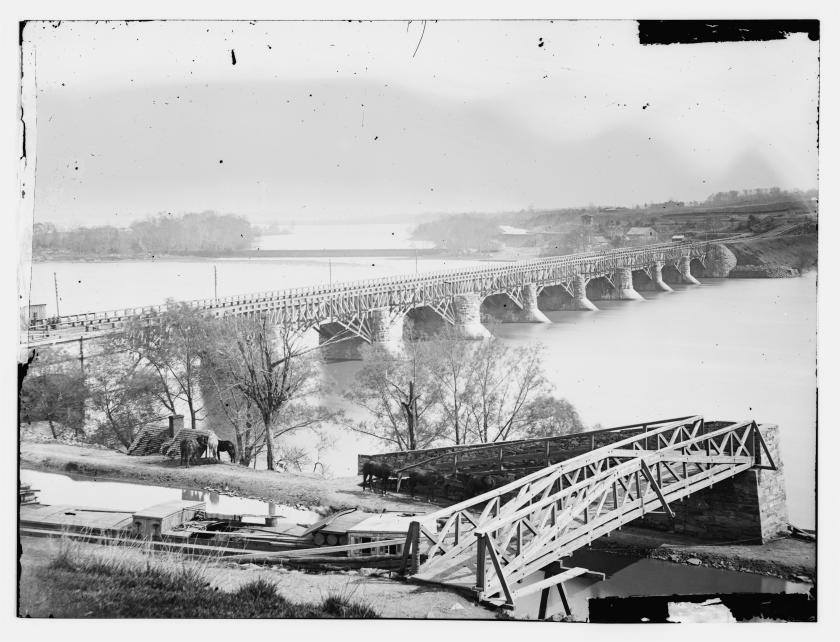

"Washington, D.C. Closer view of Aqueduct Bridge, with Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in foreground." by George N. Barnard, 1862-65.

After the United States won the War of 1812, Americans wanted to develop a domestic economy. Domestic manufacturing and improved transportation would benefit American entrepreneurs and the overall U.S. economy and would decrease reliance on European powers, particularly the British, for finished products. Americans on the eastern seaboard also wanted to move west to states in the Northwest Territory, like Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, but needed a more efficient way to travel. Dirt roads were limited in length, required travel by horse, mule, or ox-drawn wagon, and were subject to hazards like fallen trees or mud following rain. Perhaps most significantly, travelers could not easily bridge elevation changes traveling on foot, nor could wagons easily transport goods beyond local markets.

Canal construction was the solution to these problems, though the canals themselves were not without challenges, such as stalled traffic during winter freezes. These artificial waterways brought settlers to the west and, during the Civil War, states like New York and Ohio, which canals helped transform, contributed a significant number of volunteers to the Union Army. Canals, like New York’s Erie Canal and Ohio’s Ohio & Erie Canal, facilitated a domestic economy, while canals like the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, which followed the Potomac River between Washington, D.C. and Cumberland, Maryland, got caught in the crosshairs of the Civil War.

The Erie Canal was fully completed on October 26, 1825, after eight years of construction. It made New York Governor DeWitt Clinton’s vision of traversing the state between the Hudson River and Lake Erie a reality as it carved a path across upstate New York. The canal, sometimes doubted and ridiculed as “Clinton’s Ditch,” contributed to the economic importance of New York City and the state, in general. It was also an impressive engineering feat: The Erie Canal, with a water depth of 4 feet in a bed 40 feet wide, stretched 363 miles across the state, boasted 18 aqueducts to bridge ravines and rivers, and included 83 locks that enabled canal boats to navigate elevation changes. Canal boats could carry 30 tons of freight and were towed by a team of mules on a 10-foot-wide towpath. These freighter boats typically moved at approximately 4 miles per hour to prevent erosion of the canal banks. Once the Erie Canal was completed, it indeed bound the Union together as its promoters had promised. Western farmers shipped agricultural staples east, while eastern manufacturers shipped finished products west.

The domestic trade that the Erie Canal made possible impacted the loyalty of western settlers in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Given their reliance on and fondness for goods from New England, these western residents favored the Union. Since canal traffic boomed after the Erie Canal’s completion, the state of New York enlarged the canal. The project began in 1836 and was completed in 1862 as the Civil War entered its second year. The enlarged canal stretched 350.5 miles, had a water depth of 7 feet in a bed 70 feet wide, had the number of locks reduced to 72, and could accommodate boats carrying 240 tons of freight. During the Civil War, the canal played a significant role in transporting supplies for the Union war effort, despite the development of railroads, which traveled at approximately 35 miles per hour.

The Erie Canal solidified Ohio politicians’ desire to complete a canal that would stretch from Lake Erie to the Ohio River. Plans for such a canal dated back to George Washington’s survey of the Ohio Territory in the late 1700s. In 1786, Washington wondered about the practicality of cutting a canal between the Cuyahoga River, which empties into Lake Erie, and either the Big Beaver (Mahoning) River (near Youngstown) or the Muskingum River (near Zanesville) and expressed a desire to connect Lake Erie to the Ohio River to facilitate the region’s fur trade. Once Ohio gained statehood in 1803, it remained impoverished and its farmers in the Cleveland area had no way to get their crops to market. Proposals originated in the Ohio legislature in 1807 and 1808 to construct a canal that would enable Ohio’s farmers to ship their crops either across Lake Erie to the east, or south to the Ohio River to markets in Kentucky, or further, to the Mississippi River to points south.

The War of 1812 delayed construction, but once Americans emerged victorious, state legislators resurrected the canal proposal and passed the Canal Act on February 4, 1825. On July 4, 1825, New York’s Governor DeWitt Clinton arrived at Licking Summit near Columbus and, with a golden shovel, ceremoniously lifted the first shovel of dirt commencing construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal. The first section of the canal, which stretched from Cleveland to Akron opened on July 4, 1827. In just one year, Cleveland’s wheat market exploded. The number of bushels of wheat that farmers sold to Buffalo increased from 1,000 to 250,000.

The entire Ohio & Erie Canal, which stretched from Cleveland on Lake Erie to Portsmouth on the Ohio River, was 308 miles long with 146 lift locks. The canal bed was 40 feet wide at the top and 26 feet wide at the bottom, with a depth of water at 4 feet to accommodate canal boats which were towed by a team of mules on a 10-foot-wide towpath. Irish and German immigrants, many the same men who dug the Erie Canal, followed the artificial waterways to maintain employment. They worked 12-15 hours a day in harsh conditions: Laborers dug the canal with picks and shovels, felled trees with axes, hauled dirt away with wheelbarrows and were subject to diseases such as malaria. The pay was temporary housing, $5 per month, and a daily ration of a jigger (approximately 1.5 ounces) of whiskey. Job conditions and the whiskey ration contributed to a rough male culture, but supervisors looked the other way – they assumed that fighting was normal for these immigrant laborers who did not fit the white, middle-class norms of respectability. Operators of canal boats, particularly freighters, also fell short of middle-class norms. They lived on the boats year-round with their children, who often drove the mules with a “sophisticated” vocabulary. They also housed an additional team of mules in case of injury or illness to the working team.

The hard labor of lower-class immigrants contributed to a booming economy. Engineers planned spillways that stretched from nearby rivers and streams to the canal to maintain the 4-foot water depth. Mills – grist, saw, and woolen – were established on these offshoots, further contributing to domestic manufacturing. Dry docks for boat building, once concentrated on the Atlantic seaboard, now dotted the interior providing skilled jobs. Warehouses for surplus goods were located at towns that sprung up near-lock sites. There, each individual boat took approximately twenty minutes in the lock to enable passage either up or downstream and could be loaded with cargo while awaiting its turn through the lock.

Despite competition from railroads, the Ohio & Erie Canal peaked in 1851, but its usefulness declined during the Civil War. In the 1860s, expenditures began to outpace revenues because of increased maintenance costs. By 1863, intense competition from railroads caused the Ohio & Erie Canal to fall into disuse. Flooding also contributed to the canal’s downfall starting in 1861. The state of Ohio leased the canal to private owners to relieve itself of the financial burden. Private owners earned revenue from dwindling boat operation and the sale of water to factories and towns until the state resumed ownership of the canal in 1879, but the surrounding lands were sold illegally to private owners. Finally, in 1913, the Great Dayton Flood put an end to the Ohio & Erie Canal’s use.

The Erie Canal and the Ohio & Erie Canal were removed from battlefield conflict during the Civil War, but the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal sat on the dividing line between North and South as it followed the Potomac River’s Maryland shore. Construction commenced on July 4, 1828, and lasted until 1850. Once complete, the canal stretched 185 miles from Washington, D.C. to Cumberland, Maryland and remained in operation until 1924.

When the Civil War broke out, its workers reflected the sectional tensions that tore the nation apart, and Union and Confederate troops vied for control of the strategic waterway. Boatmen loyal to the Union hoped that Union soldiers would protect them from Confederate raiders who wanted to disrupt the flow of supplies, troops, and coal transported on the canal to U.S. soldiers and sailors. Union soldiers, however, sometimes took these boats to make floating pontoon bridges which, in addition to Union and Confederate soldiers potentially stealing mules or sinking boats to stall traffic, damaged their livelihoods.

Initially, Confederate troops near Harpers Ferry were reluctant to target the canal since they did not want to risk generating Union sympathy among Maryland residents and left the canal alone. By December 1861, however, General Stonewall Jackson’s Confederates tried to destroy one of the dams which were key to the canal’s operation, but Union soldiers helped canal workers repair the dam after the Confederate withdrawal which allowed the canal to reopen and boatmen to get paid. Later in the war, the canal saw additional action: Confederate cavalry under J.E.B. Stuart and John Singleton Mosby raided the canal. Union and Confederate soldiers continued to take mules for their respective war efforts, and the armies crossed over the canal during the Antietam and Gettysburg campaigns.

After the war, the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal’s revenues declined which, like the Ohio & Erie Canal, eventually led to its closing. Railroads offered more efficient transportation and a massive flood in 1889 required $1 million in repairs and halted operations for a year and half. Finally, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad line purchased the canal and operated it, despite insufficient revenue, until 1924 when another flood halted its use for good.

Canals are now a relic of the past, but those curious about the canal era can walk the footsteps of mule-drivers who traversed the towpaths of the Erie, Ohio & Erie, and Chesapeake & Ohio Canals, walks that can inspire thoughts on how the canals boosted agricultural and industrial production, improved settlers’ quality of life, knit the nation together between the War of 1812 and the Civil War, and became embroiled in this war that temporarily tore the nation apart.

Further Reading:

- The Grand Idea: George Washington’s Potomac and the Race to the West By Joel Achenbach

- The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817-1862 By Carol Sheriff

- Ohio’s Grand Canal: A Brief History of the Ohio & Erie Canal By Terry K. Woods