By Kara E. Kozikowski

Throughout the American Civil War, as vast armies in blue and gray clashed on conventional battlefields, a drastically different kind of conflict was raging as well: a bloody guerrilla war that erupted in the South in response to Federal invasion. Characterized by ambushes, surprise raids, and irregular styles of combat, this guerrilla war became savage, chaotic, and often disorganized. The guerrilla war, as waged by both Confederate guerrillas and Unionists in the South, gathered in intensity between 1861 and 1865 and had a profound impact on the outcome of the war.

As soon as the Civil War broke out in April 1861, guerrilla warfare emerged as a popular alternative to enlistment in the Confederate army. Fearful of the imminent Federal invasion, secessionist civilians throughout the Midwest, upper South, and Deep South wasted no time organizing themselves into guerrilla bands to independently resist Yankee occupation. Fighting as a guerrilla was attractive: it would allow men more freedom than they would enjoy in the regular army, and most importantly, would allow them to remain at home to defend their families and communities.

Several different kinds of guerrillas emerged during the Civil War. The majority of Civil War guerrillas were called bushwhackers, so named because of their tendency to hide behind foliage and forest lines, what Union soldiers referred to as "the bush," and attack their foes. Bushwhackers were un-uniformed civilian resisters, who had no affiliation with the Confederate army, and were a source of constant confusion for the Union army who had no way of distinguishing a peaceful Southern civilian from one who would attack them later. Partisan rangers arose as a more legitimate kind of guerrilla in 1862 when they were sanctioned by the Confederate Congress’ passage of the Partisan Ranger Act, an act which allowed men to enlist for service in a partisan corps rather than the regular army. Partisans were groups of men who, like the bushwhackers, operated independently and with irregular tactics, yet they wore Confederate uniforms, had leaders who held Confederate commissions, and were responsible for reporting to a superior in the Confederate army.

Owing to the large difference between bushwhackers and partisan rangers, the Union Army was initially unsure of how they should deal with guerrillas. In 1862, Gen. Henry Halleck issued the Lieber Code, which was written by philosopher Dr. Francis Lieber and issued to Union commanders as General Orders No. 100. The Lieber Code detailed the differences between bushwhackers and partisans, and stated that bushwhackers were illegal combatants, and could be shot if captured. Since partisans belonged, however loosely, to the Confederate Army, they had to be treated as prisoners of war.

The Civil War has often been characterized as a brother’s war in which neighbor fought against neighbor, and this interpretation certainly applies to the war’s guerrilla element. Throughout the South, Unionist sympathizers organized in small numbers as guerrillas to defend themselves against secessionist members of their communities. Typically referred to as Jayhawkers in the Midwest and Buffaloes in the East, these Unionist guerillas took up arms against the bushwhackers. Although they would play a relatively minor role throughout the war, their Confederate guerrilla counterparts would significantly impact the Civil War in nearly every Southern state.

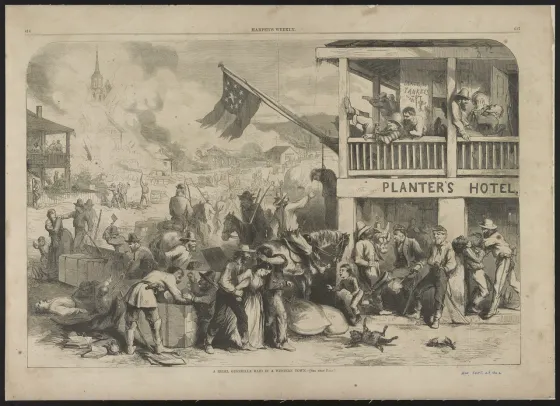

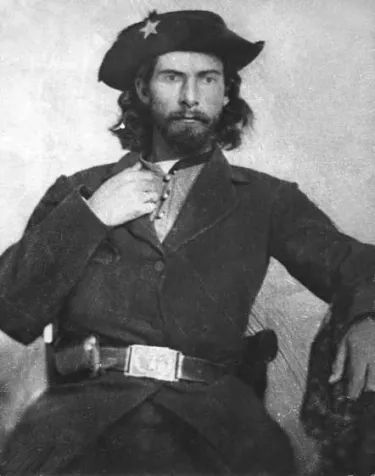

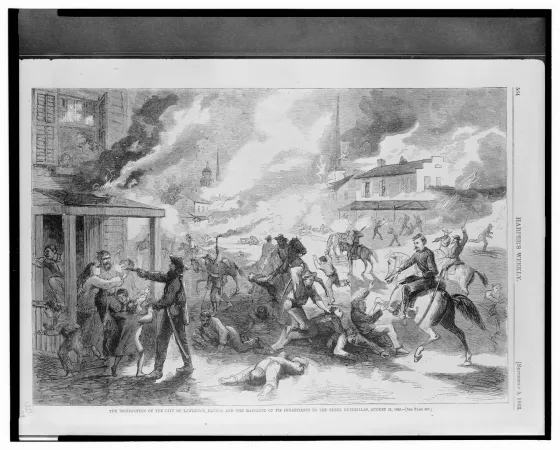

In every section of the Confederacy, the guerrilla war took on its own shade and character. It emerged early on at its most intense in the Midwest, exploding in early 1861 in Missouri. It immediately became savage and barbaric, fought mainly by bushwhackers who behaved more like outlaws. Men such as William Clarke Quantrill and William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson carried out raids which amounted to little more than murder sprees. In 1863, Quantrill killed 200 men and boys in the Unionist town of Lawrence, Kansas, and in 1864, Anderson led the famous Centralia Massacre, in which his men – including a young Jesse James – pulled 24 unarmed Union soldiers off a train and executed them. Unionist Jayhawkers would post an equal threat to Midwestern society as they preyed on secessionist families and attempted to wipe out the Confederate bushwhackers.

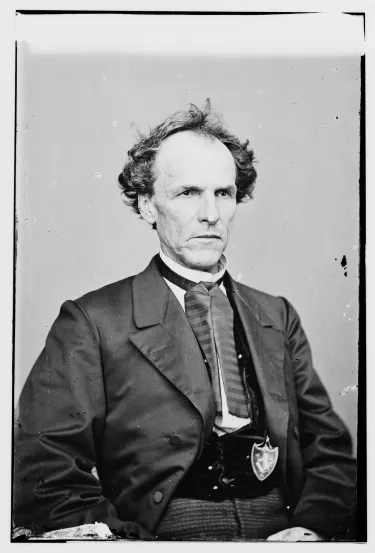

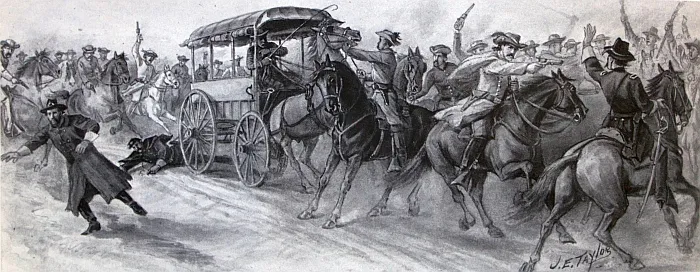

Guerrillas and partisan rangers in the east, however, focused their attention on harassing the Yankee invaders, and soon emerged as a real and constant threat to the Union army. These irregulars attacked Union pickets and small, vulnerable groups of Union men. They intercepted Union supplies, cut communication lines, destroyed rail cars and railroad track, carried out surprise raids, and often donned blue uniforms to invade Yankee camps. These tactics frightened and demoralized Union soldiers, a phenomenon which came to a head in 1863 with the formation of Col. John Singleton Mosby’s 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry, a partisan ranger band. Known as the Gray Ghost, Mosby defied Union troops stationed in Virginia for two years. So incapable were the Federals at putting a stop to Mosby’s activities that by the end of 1863 Northern Virginia and the Shenandoah Valley became known as “Mosby’s Confederacy.”

The efforts of guerrillas to antagonize the Union army were undeniably successful. In response, Union commanders tried sending out scouting parties to capture the guerrillas. These attempts, however, accomplished little. Guerrillas, who had the advantage of surprise and knowledge of the territory, were nearly impossible to catch and efforts to capture them only distracted soldiers from fighting the Confederate army. Their inability to stop the guerrillas who continued to destroy Union supplies and kill Union men encouraged a growing dislike among Northern soldiers for the Southern population from which the guerrillas came. By late 1862, the Union Army, overwhelmed by fighting a conventional army in their front and a guerrilla threat from all sides, began to meet guerrilla action with “hard war” policies. Union commanders began to hold civilians responsible for the actions of guerrillas, often by burning homes and communities, arresting civilian non-combatants, and in some cases evacuating entire counties. By 1865, the guerrilla war throughout the South had become confused, bloody, and disorganized. The Union Army had ceased to tolerate guerrillas, and met their attacks unhesitatingly with retaliation. Civilians, exhausted by the violence in their communities and hopeful of preventing Federal retaliation against their homes, lost their support for the guerrilla movement and it soon began to die out.

Despite the significant role that guerrillas played during the war, academically they have received very little attention. Early Civil War historians characterized guerrillas as interesting yet irrelevant, and as a result the importance of guerrillas during the Civil War has been largely understated. Today, however, historians are beginning to recognize the role that guerrillas played in shaping both the outcome of the war and wartime society. Guerrillas, whether they fought as bushwhackers, jayhawkers, or partisan rangers, influenced both the Confederate home front and Union military policy, and proved to be important, if slightly overlooked, figures in the American Civil War.

Sources:

Ash, Stephen V. When the Yankees Came: Conflict and Chaos in the Occupied South, 1861-1865. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Grimsley, Mark. The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy toward Southern Civilians, 1861-1865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Mackey, Robert R. The UnCivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865. Norman: The University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Sutherland, Daniel E. A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Learn More: Logistics of the Civil War