The Parker’s Ferry Battlefield retrains an air of mystery suitable to the legend and legacy of the Swamp Fox.

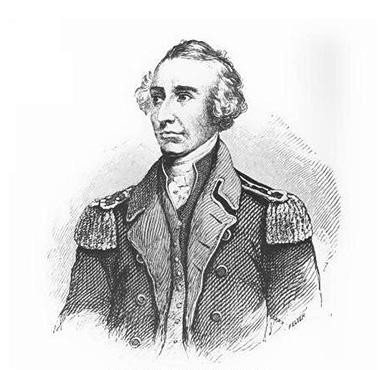

By the time of the Revolutionary War, Francis Marion, best known to history as the Swamp Fox, was acquainted with both conventional and irregular warfare. By then a trained Continental officer who had helped repulse the British at Fort Sullivan alongside Colonel William Moultrie, Marion had initially been recruited into service during the French and Indian War at age 24 by Captain John Postell in 1757, and then participated in South Carolina’s 1759–61 attacks into Cherokee lands.

Marion was a student of Major Robert Rogers’s 28 Rules of Ranging, and in his long military career, Marion formulated, practiced and executed his own particular modes of “maneuvering.” The United States Marine Corps’ modern doctrinal manual, Warfighting, defines maneuver warfare as “a state of mind bent on shattering the enemy morally and physically by paralyzing and confounding him, by avoiding his strength, by quickly and aggressively exploiting his vulnerabilities, and by striking him in a way that will hurt him most.” The sentiment certainly applies to Marion’s approach.

By the time of the Revolutionary War’s Southern Campaigns of 1780–1782, enterprising 48-year-old Patriot partisan General Francis Marion did everything in his power to effectuate Rogers’s concepts in the Carolinas following the surrender of Charleston. His philosophy, as described by the Harvard Business Review in a description of how the practice can be adapted beyond the battlefield, amounted to “not … destroy[ing] the adversary’s forces but … render[ing] them unable to fight as an effective, coordinated whole.… Instead of attacking enemy defense positions, maneuver warfare practitioners [to] bypass those positions, capture the enemy’s command-and-control center in the rear, and cut off supply lines. Moreover, maneuver warfare doesn’t aim to avoid or resist the uncertainty and disorder that inevitably shape armed conflict; it embraces them as keys to vanquishing the foe.”

Ultimately, as a result of Marion’s simpler, straightforward execution of innovative techniques, guerrilla tactics, interdiction and irregular warfare, liberty was slowly won blow by blow in South Carolina combat. The hand of fate was also in play for Marion’s success. First, he escaped the surrender of Charleston because he was recuperating from a broken ankle away from the city. Then, days before the Battle of Camden, Marion and two dozen men rode into General Horatio Gates’s camp offering assistance. These men were scruffy, backcountry Williamsburg District militia. Colonel Otho Holland Williams, adjutant general, asserted that Gates was “glad of an opportunity of detaching” the “burlesque” Marion away into the South Carolina interior. Whatever the reason, by August 15, 1780, Gates ordered Marion to “go Down the Country to Destroy all boats & Craft of any kind” to prevent British troops from escaping Camden. The dismissal spared Marion being captured or killed in that devastating Patriot loss.

The Rise of the Swamp Fox

After Camden, un-civil warfare magnified on both sides, exacerbated by civil strife and other forms of violence, igniting an epistolary barrage amongst Patriot and British commanders. Marion was particularly upset after his old friend Captain John Postell was captured by the British while under a white flag of truce in March 1781. “The hanging of men taken prisoners, and the violation of my flag will be retaliated, if a stop is not put to such proceedings, which are disgraceful to all civilized nations. All of your officers and men who have fallen in my hands have been treated with humanity and tenderness; and I wish sincerely, that I may not be obliged to act contrary to my inclinations, but such treatments as my unhappy followers whom the chance of war have thrown in my enemies’ hands meet with such, such must those experience who fall in my hands,” wrote Marion.

As 1780 wore on, the Williamsburg District was transformed by Marion’s emergence, seemingly mocking the British claim to have subdued South Carolina. Major General Charles, Lord Cornwallis assigned the destruction of Marion’s Brigade to that rapid-riding, hard-charging British Legion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton. Marion set out to ambush the small troop then escorting Tarleton, who had descended upon Colonel Richard Richardson’s plantation, stripped his house and set it afire. In turn, Marion realized that the British were also on their way to seize him. On November 8, Tarleton vigorously pursued Marion from Jack’s Creek northwest of Nelson’s Ferry for 20-plus miles east to Ox Swamp. Marion’s men galloped through the swamp’s watery morass along trails that few could have followed. With dogged determination equal to Marion’s, Tarleton drove his men forward until they reached the Woodyard. Tarleton’s Legion could not cross that swamp in the dark, resting at its edge for the night.

Marion would not retreat indefinitely, deciding to make a stand near Benbow’s Ferry. With felled trees blockading paths and swamps protecting their rear and flanks, Marion’s marksmen awaited the man whom Patriots called the “Butcher.” Tarleton’s men swung around the swamp’s edge, hoping to again pick up Marion’s trail on its opposite side. For seven hours, the British officer drove Legion calvary, wagons and two artillery pieces at a pace that made his horses drop in their tracks. Riders who lost their mounts were left to trot along exhaustedly. Tarleton’s scouts reported that the route headed into miry Ox Swamp. Unable to discover a trail across or through it, Tarleton despaired after intensely chasing so long through the swampy morass to no avail.

Tarleton is credited with declaring, “Come my boys. Let us go back, and we’ll soon find the Gamecock [Thomas Sumter]. But as for this damned old Fox, the devil himself could not catch him!” This earned moniker struck true and spread quickly. Incredibly daring, the great guerrilla fighter terrorized the British Army in South Carolina, swiftly striking, then vanishing ghost-like from fields into swamps.

The Exemplar Victory

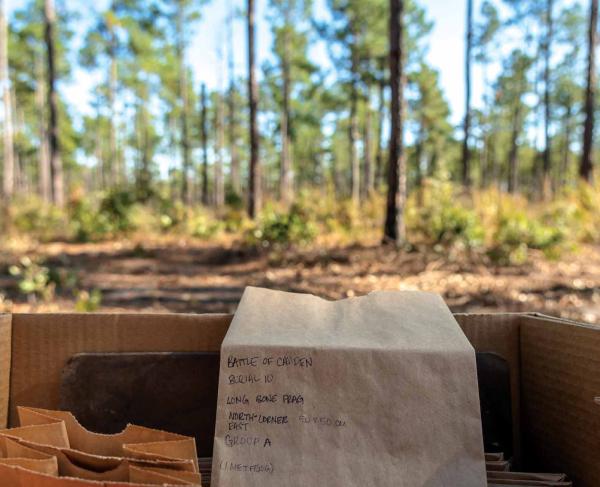

Parker’s Ferry was a major thoroughfare crossing the Pon Pon River (Edisto River) about 33 miles west of Charleston. Here, Brigadier General Francis Marion planned a famously successful ambush. British and Loyalist troops were operating in the summer of 1781 throughout the Low Country around Charleston, foraging for provisions and attempting to suppress the Patriot militia. On August 10, 1781, Major General Nathanael Greene dispatched Marion to assist Colonel William Harden’s Patriot militia. Marion learned that a Loyalist force of 100 troops, commanded by William “Bloody Bill” Cunningham, was at the Pon Pon River to join a larger force of British regulars, Hessians and other Loyalist militia.

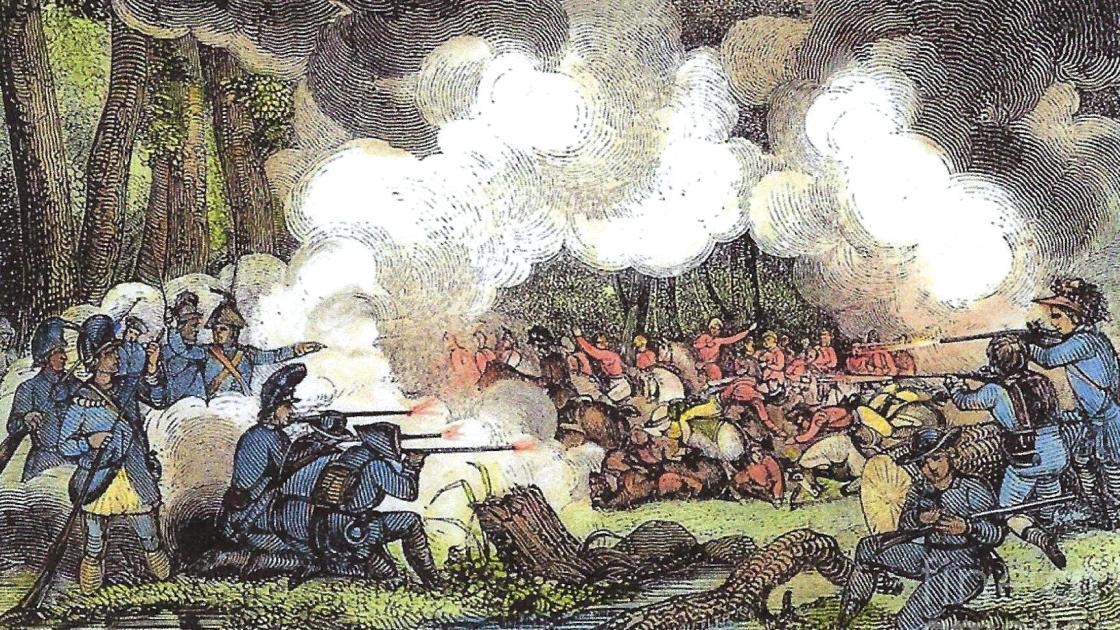

Marion placed his 445 troops in the thick woods about the causeway leading to Parker’s Ferry, a mile away. Several dragoons galloped forward to entice the more than 600 Loyalist, British and German troops into a Patriot trap. As shots were fired, British Lieutenant Colonel Ernest Leopold von Borck ordered Major Thomas Fraser and his dragoons to charge to the scene. Fraser’s troops galloped blindly into the “gauntlet” that Marion had set for them.

Harden’s men moved back 100 yards from the ambush line so they could be used as reserves. Major Samuel Cooper’s 60 swordsmen were told to attack the rear of the enemy after the ambush was initiated. They then waited for the British, as von Borck left camp in midafternoon with his infantry, accompanied by two pieces of artillery in front of the column and Fraser’s mounted South Carolina Royalists in the rear. It was almost dark when they stumbled into a firefight between Marion’s men and Loyalists who had just discovered them. Fraser sent Lieutenant Stephen Jarvis charging forward while he placed three other divisions on the road and to the left and right of the road. Mounted Patriots charged Jarvis, who reversed course quickly. Fraser believed these to be Harden’s men and ordered his cavalry in full gallop to intercept them. Marion now had the British right where he wanted them, and instantly Fraser’s horsemen were surprised. At 40 yards, the Patriots opened with buckshot and downed the British dragoons. Fraser rallied and tried to charge, but the Patriots delivered a second and a third volley. There was no way for Fraser to attack into the thick trees and nearby swamp, so he withdrew down the causeway, down the full length of the ambush. British Captain Archibald Campbell was wounded twice, and Fraser was badly bruised when his horse was killed, and the rest of his cavalry rode over him as he lay in the road.

British casualties, at 125 killed and 80 wounded, were heavy, while Marion suffered only one man killed and three wounded. Marion’s victory at Parker’s Ferry on August 30 directly impacted the Battle of Eutaw Springs nine days later by depriving British of horses not available to fight there on September 8. Marion maneuvered through enemy territory back to the Santee River and joined Greene to command that battle’s right militia line at Eutaw Springs. Parker’s Ferry is the exemplar of Marion’s guerilla warfare tactics.

Avenue of the Cedars August 29, 1782

Almost exactly one year later, Marion participated in his final battle, Avenue of the Cedars, on August 29, 1782. British Major Thomas Fraser’s Royalists were dispatched to get needed meat for the British in Charleston. They crossed the Cooper River to surprise the Patriot guards at Biggin Bridge and Strawberry Ferry. Marion had finished with Georgetown, returning to his post at the old Sir John Colleton plantation house on the south side of the Wadboo Creek. When Marion learned of the approaching foraging party, his cavalry patrolled down the Wadboo looking for British galleys. He sent Captain Gavin Witherspoon to find Fraser. Part of Marion’s troops were positioned to the side of a cedar-lined avenue, ready for ambush. The rest were placed in and around nearby slave cabins. Joining Marion for the first time was Major Micajah Gainey’s 40 men, all who had recently “converted” from Loyalist to Patriot.

Fraser approached, capturing some of Marion’s pickets. He detected and charged Witherspoon in the woods. Witherspoon and his men turned back toward the plantation house at a full gallop. They fell behind in the ambush kill zone to let the Loyalist cavalry catch up. Fraser’s more than 100 British dragoons confidently charged the Patriot infantry and cavalry force. As Fraser’s dragoons came within 30 yards of the ambush site, Marion’s hidden men simultaneously cheered and fired a volley. Fraser tried to rally his men as they were being cut down on both sides of the road. During the skirmish, a Patriot wagon full of ammunition was lost. Too low on ammunition, Marion retreated to the Santee River. The British lost one captain and between three-eight enlisted men, several were wounded and one was captured. Marion had no casualties in his last combat.

For all his maneuvering, machinations, menace and manpower, General Nathanael Greene best condensed Marion’s characterization in a letter written the day before the Hobkirk Hill debacle in April 1781. “When I consider how much you have done and suffered, and under what difficulties you have maintained your ground, I am at a loss which to admire most, your courage and fortitude or your address and management. Certain it is, no man has a better claim to the public thanks than you. History affords no instance where an officer has kept possession of a country under so many disadvantages as you have. Surrounded on every side with a superior force, hunted from every quarter with veteran troops, you have found means to elude their attempts, and to keep alive the expiring hopes of an oppressed militia, when all succor seemed to be cut off. To fight the enemy bravely with the prospect of victory, is nothing; but to fight with intrepidity under the constant impression of defeat, and inspire irregular troops to do it, is a talent peculiar to yourself. Nothing will give me greater pleasure than to do justice to your merit, and I shall miss no opportunity of declaring to Congress, to the commander-in-chief of the American army, and to the world, the great sense I have of your merit and your services.”

Legends aside, Francis Marion’s daring leadership diminished British control in the South. The best revelation of the intensity and enormity of Francis Marion’s revolutionary maneuvering is in visiting the South Carolina swamps and fields where his men trekked to arms for liberty.

Related Battles

1,900

324

579

882

4

205