Each items is carefully cataloged and labeled before removal from the site.

Just north of Camden, South Carolina, the landscape transitions from bustling urbanity to scattered homesteads and expansive longleaf pine forests. On August 16, 1780, this region on the edge of the prehistoric Atlantic Ocean now known as the Sandhills was the setting for the turning point of the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution, the Battle of Camden.

After Charleston fell to the British on May 12, 1780, the hero of Saratoga, Major General Horatio Gates, arrived in the South with plans to replicate his victorious campaign in the North. Gates marched for Camden to capture the outpost there. Meanwhile, Major General Baron de Kalb and more than 1,000 Maryland and Delaware Continentals were marching south from Morristown, New Jersey, on orders from General George Washington. Things were about to get serious in Camden and Gates’ troops were severely compromised. Food rations were nearly non-existent. His soldiers foraged on green corn and green peaches, a decision that caused them to be “breaking the ranks all night [as they] were certainly much debilitated…”

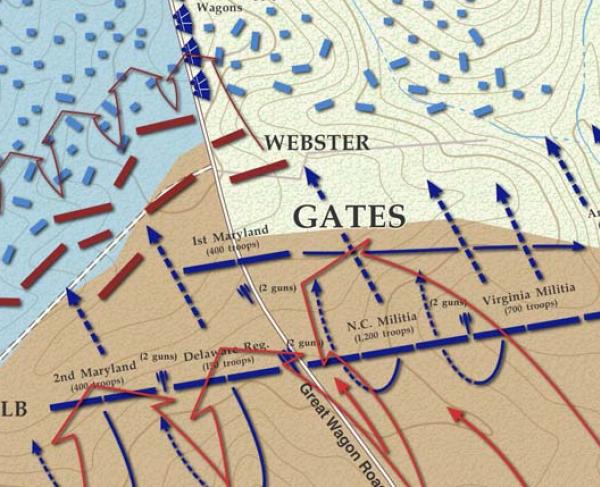

In the early hours of August 16, Lord Cornwallis’s 2,335 troops and Gates’s approximately 3,500 Patriots literally ran into each other on the Waxhaw’s Road, eight miles north of Camden. After a short skirmish, both sides fell back to regroup. At early morning light, the two armies faced each other in earnest, separated by about 200 yards of longleaf pine forest. Although, on paper, the Americans enjoyed numerical superiority, all but about 1,250 of their number were inexperienced new Virginia and North Carolina militia. Cornwallis’s forces were a mix of Loyalists and veterans with Simon Fraser’s Highlanders, known officially as the 71st Regiment of Foot.

“The battle, of course ended up being a total disaster,” commented James Legg, public archaeologist for the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology (SCIAA). “The American Army was destroyed for the second time in four months.” Legg has spent decades researching the battle and thousands of hours on the battlefield. He described a setting where musket fire at close range continued for 45 minutes or more before the British outflanked the Patriots and claimed victory.

We may never know how many soldiers lost their lives at Camden. When faced with charging bayonets, many Patriot soldiers fled to the north and west. Some were captured. Others were left dead or wounded where they fell. Burials were unceremonious affairs in shallow single or mass graves. Historical records indicate that many others remained on the surface, their remains removed by wolves and other scavengers. Legg continues, “No one was ever removed. They didn’t get up and go home. They are still right where they fell.”

In the years following the battle, the landscape remained remarkedly intact. The site was not developed or paved over; however, shallow graves left the soldiers’ remains vulnerable to the impacts of logging and agriculture. The Hobkirk Hill chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, who preserved the first two acres, moved to have the battlefield listed on the National Register of Historic Places in January 1961. The Palmetto Conservation Foundation acquired a large portion of the battlefield and provided the initial light interpretation. In 2017, ownership of the battlefield was transferred to the Historic Camden Foundation. In 2018, the American Battlefield Trust and the South Carolina Battleground Trust, through their Liberty Trail initiative, acquired and preserved an additional 294 acres of the battlefield. All 770 acres of the battlefield are now protected under a conservation easement held by the Katawba Valley Land Trust and enjoyed by visitors using the The Liberty Trail app.

Legg describes Camden as a “featureless battlefield.” The site is a pine forest with no structures such as fortifications or trenches – the only evidence comes in the form of artifacts. Much of the early research conducted by Dr. Steven Smith, a research professor affiliated with SCIAA since 1986, involved the identification of artifacts, located either by interviewing relic hunters or utilizing systematic metal detecting. Research conducted throughout the early 2000s yielded dense concentrations of arms-related artifacts such as lead shot and musket balls, and clothing artifacts such as buttons and clothing clasps, all within six to 18 inches of the surface. The artifacts were catalogued, and the locations were mapped for later work. In 2020, Legg finally confirmed that the collections of buttons marked burials.

South Carolina Battleground Trust CEO, Doug Bostick worked closely with Legg and Smith over the years. He knew that the remains were vulnerable, felt strongly that America’s first veterans deserved a permanent resting place that honored their service and protected their remains and set a course to achieve that. “The soldiers who fell at Camden fought a vicious, bloody battle for the liberties we enjoy today,” Bostick remarked. “They are heroes who deserve to be remembered as such.” In the Fall of 2022, he contracted with SCIAA for the excavation of the remains of five to six soldiers and assembled a steering committee to begin the planning for reinterment ceremonies in April 2023.

A cross-disciplinary team of archaeologists from SCIAA and the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources and biological pathologists from the Richland County Coroner’s Office under the leadership of Smith and Legg began the work to recover the soldiers over an estimated timeline of four weeks. As the archaeological units were opened, however, graves believed to hold one individual were found to hold several, and the timeline extended from four weeks to eight.

John Michael Fisher, an archaeologist for SCIAA, has personal connections to Camden and served his country in the U.S. Army Reserves. “My grandfather used to take me on rides throughout the state to see battlefields or historic sites. Camden was always important to him. We had a family member who fought in the Revolution and disappeared at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.” He continued, “As a veteran, I felt humbled to be there. I’m a combat veteran, so seeing these guys who marched all the way from Maryland exhausted, and then died and were thrown into mass graves, made me personally attached to this project.”

Fisher and his colleagues worked with excruciating care to remove soil from the remains with a collection of wooden spoons, chopsticks and small brushes. They relied on the biological pathologists from the Richland County Coroner’s Office to lead the final removal in a manner that would not cause additional harm to the fragile bones. Deputy Coroner Bill Stevens has extensive experience in the recovery of remains. “We treat remains with dignity, especially those who have died in a conflict. That was the case for me working in Guatemala, and later in Cyprus, in the Mediterranean, and here at Richland County, where we provide services for homeless veterans, dealing directly with Fort Jackson to provide them burial with full military honors.”

The recovery of Revolutionary War soldier remains is rare. The manner of their burials, coupled with human or animal disturbance, weather, and soil chemistry, often results in the loss of these individuals and their stories. Stevens credits the partnership of experts in developing field protocols that will provide additional insight into these heroes and provide an opportunity to ensure they are forever remembered. “The project allowed us to develop a lot of different protocols using each others’ expertise. The Department of Natural Resources, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina and the Richland County Coroner’s Office all have different skill sets for dealing with remains and material culture artifacts, knowledge about the soil, about the conditions of burial and historical knowledge to identify individuals. It’s been a great melding of experts that allowed us to carry out the field recovery as we did and continues into the lab analysis.”

Camden’s material artifacts are helping to shed light on the soldiers’ stories. Unique buttons lying among the remains helped researchers identify the remains as 12 Continentals, one Loyalist militiaman, and one British soldier from the 71st Regiment of Foot. Continental buttons prominently featured the letters “USA” in an overlapping design. The soldier of the 71st was found with 22 uniform buttons with a decorative border and the numbers 7-1. The careful excavation also provided insight on the manner of death for many of the soldiers: a musket ball lodged in the spine or in the skull paints a clear picture.

The manner of burial was one of the most emotionally challenging finds for those who worked daily on the battlefield. While the Fraser’s Highlander was presumed to be carefully and respectfully buried, face up with his arms across his chest, the Continentals were found in a much different condition. Four graves were single burials, and three were multiple burials. South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Archaeologist Tariq Gaffar described his experience. “I’ve done disinterment before both of large cemeteries and individuals, but this would be different because this is the first time I’ve dealt with individuals who have died by violent means.” He continued, “There was a tremendously callous and brutal treatment of their bodies. They were not carefully or lovingly buried. They weren’t marked. So I feel as though my role here is not so much as a doctor or healer, but as a rescuer. I’m glad that they are going to finally get the military honors that they have deserved for hundreds of years.”

That sentiment was common among the team, resulting in the creation of a short informal ceremony before and during the final removal of the soldiers. Bostick described those moments, “They were carefully removed. Each body was wrapped, boxed. Someone would say a few words. Another would offer a prayer. The flag-draped box of remains was then carried to the coroner’s van by a member of the team who was also a veteran.”

The Richland County Coroner’s Office is studying the soldiers’ remains to learn more about where they came from, their diets, their ages and stature. DNA samples are also being collected, and once this work is complete, staff will prepare the remains to be placed in handcrafted replica 18th-century coffins and to be returned to Camden for two days of reinterment ceremonies. At the conclusion of the ceremonies, the coffins will be placed in sealed vaults, in the precise location where the remains were initially recovered, and the graves will be marked.

“This will be a one-of-a-kind event. The opportunity to respectfully bury these soldiers who did not have the opportunity to be respectfully buried in 1780,” Bostick reflected. “We invite you to come to Camden to immerse yourself in the Revolutionary War. This is going to be a ceremony that none of us will see in our lifetime again. To do so, with full military honors is what these soldiers deserve.”

Related Battles

1,900

324