The Governor's Palace, Williamsburg, Va.

One of the prevailing myths of the American Revolution is that the Southern colonies were pro-British. Though Great Britain was able to create Provincial and Loyalist units in the South, the majority of inhabitants of Virginia, North and South Carolina were either Patriots or indifferent to either side. The South had a lasting impact on the Patriotic cause through its political, geographical, and military influence. Many of the war’s first military actions occurred in the South and some of the earliest movements towards independence originated in the very same space.

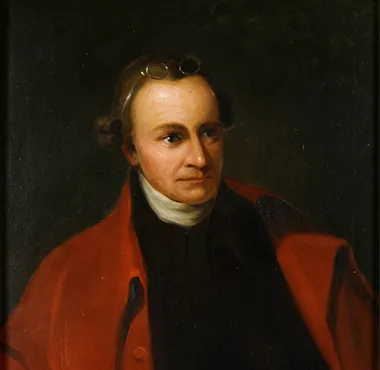

In 1776, Virginia was considered the lynchpin of the new states. One of the largest and richest, Virginia boasted great political leaders with significant influence. As the war started in the spring of 1775, Virginia Royal Governor John Murray, Earl of Dunmore underestimated the revolutionary fervor in his colony. Leaders such as Peyton Randolph and the fiery Patrick Henry were seen as leaders for both Virginia and American independence. By June 1775, Dunmore fled Williamsburg for a warship to find a way to defeat the upstart Virginians on the battlefield. At that time, the Virginia Convention acted as Virginia’s government, and the duties of the executive were entrusted to an eleven-man Committee Safety (also chaired by Edmund Pendleton). In May 1776, the Committee fully endorsed independence and the Virginia Convention directed Richard Henry Lee to propose independence at the Second Continental Congress.

Virginia’s newly established General Assembly elected Patrick Henry as its first state governor on July 5, 1776, under a new state constitution. Henry was a proponent of independence and was one of the main authors of the May legislation asking for Congress to declare independence. Henry oversaw a new state government that attempted to supply the Continental armies in the field. During his tenure, Henry observed the weakness of Virginia’s Navy and militia in comparison to the Royal Navy, a forerunner to a much larger incursion that Governor Thomas Jefferson witnessed a year later.

Virginia Governors Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson grappled with how to defend Virginia. With its several hundred miles of coastline a and several navigable rivers, the British Navy was advantageously positioned to strike. Jefferson worried about Virginia’s lack of defenses and manpower. Virginia sent thousands of men via Continental and militia service north to serve in Washington’s army. Virginia also served as a supply source for Washington’s armies.

In North Carolina, Royal Governor Josiah Martin watched cautiously at the local forces formed outside of his home at Tryon Palace. On April 24, 1775, Martin was forced out of his home and sought shelter in a sloop of war. Martin tried to establish a stronghold on the Cape Fear River, but by July Martin was back on a ship off the North Carolina coast.

North Carolina’s shift towards independence was first declared on May 20, 1775, in the Mecklenburg Resolves. These resolves called for the vacation of all British laws and authority. A year later, the North Carolina Provincial Congress passed the Halifax Resolves, which called on the Continental Congress to declare independence. Much like Virginia, North Carolina’s legislature created a Council of Safety that acted as the executive branch of the new government. With a new state constitution, the state legislature annually chose a Governor who could serve up to three out of every six years. The first Governor under the new state constitution was Richard Caswell. Caswell was a popular choice as he served in the Continental Congress and acted as commander of Patriot forces at Moore’s Creek Bridge. Caswell was a popular governor, but as his term came to an end, the British were knocking on the door of Charleston, SC which triggered Patriots to act throughout the South. The next Governor, Abner Nash, appointed Caswell Major General of the North Carolina militia and state troops.

By the time South Carolina Royal Governor Lord William Campbell arrived in Charleston, things were quickly progressing towards independence. In January 1775, Charleston leaders from the former colonial legislature created an extralegal Provincial Congress to attempt to govern the colony. Campbell endeavored to play on the divisions between the low and back countries by playing them against each other. But by June 1775, events progressed too far and by September he fled the city. Sadly, Campbell was wounded in the Battle of Sullivan’s Island the following June and he died two years later.

The natural leader for South Carolina to choose to lead through this transition was John Rutledge, an experienced leader that served on the First and Second Continental Congresses. He resigned in March 1776 when the new South Carolina state assembly elected him “President” of South Carolina for a two year term. Laurens supported independence but did not have the time to focus on politics as the area increasingly became the target of British military conflict. By June 1776, the British determined to attack and capture the south’s largest and most important city, Charleston.

In 1780, when the British captured Charleston (and most of the Virginia Continental line) Virginia was called upon to provide supplies and men for a new southern army. Major General Horatio Gates grew very frustrated with the lack of support Virginia provided his new southern army then encamped in North Carolina. A few months after the American disaster at Camden, Jefferson, and the Virginia government, were in full flight from Richmond due to Benedict Arnold’s raid on Virginia. Though Washington sent Lafayette and Baron von Steuben to combat the British, Arnold and other British forces moved easily around Virginia.

Consequently, the defeat at Charleston and Waxhaws a few weeks later left South Carolina with no organized force to defend itself. The British planned to establish outposts and rely on what they believed would be a large turnout of Loyalist militia. Governor Rutledge escaped Charleston and governed the state from various sanctuaries. Though Washington was sending more men under Maj. Gen. Baron de Kalb and then Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, Rutledge looked to two places to help defend his state. Partisans and North Carolina.

Governor Rutledge also worked hard to fight the British with partisans such as Thomas Sumter and Francis Marion to raid British outposts and supply lines while buying time for neighboring states to send help. North Carolina’s former governor, now militia general Richard Caswell, was working on gathering a large militia force to threaten the British in South Carolina and defend North Carolina. This force was located near the North and South Carolina border and by August 1780 it consisted of over 2,000 militiamen. Caswell decided to move south into South Carolina and await the arrival of Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. This force unfortunately was part of the force routed at Camden on August 16, 1780.

Southern governors, contrary to popularly held perception, were under constant pressure from British incursions. Most popular histories of the American Revolution portray the South as a pro-British region that did not get involved in the war until 1780. Evidence suggests the southern citizenry and leaders supported the revolution and independence with fervor. Even with the surrender of Charleston and the disaster at Camden, the Patriots were able to rebound and within weeks be back in the field under arms. The war in the South was truly a violent civil war between neighbors and families. It took strong leadership from its leaders to stay the course and be a deciding factor in winning independence.

Related Battles

5,506

258

316

17

1,900

324

579

882