Shortly after the pro-Southern Missouri Guerrillas sacked the Kansas Jayhawker capital at Lawrence in August 1863, a New York Daily Times correspondent attached to the federal cavalry reflected on the Guerrillas’ knowledge of local geography, tactics and strategy. Under the command of notorious chieftain Capt. William Quantrill, the Guerrillas, he wrote, “follow the hog-paths through the woods, knowing every foot of ground, and [are] able to evade us at every mile they traverse.”

Unlike many of the larger armies of the Eastern and Western Theaters of war, frontier units on both sides — such as the Missouri Guerrillas, Kansas Jayhawkers and Cherokee Mounted Rifle regiments, as well as Rebels under Meriwether Jeff Thompson — had a remarkable knowledge and understanding of the geography of the land in which they operated, which led to their repeated successes on the battlefields of the Trans-Mississippi West.

Antebellum Atrocities

For the young United States, the frontier had been a fluid boundary between society and the wilderness. As the country expanded westward throughout the early to mid-19th century, so did the frontier. Americans across all classes were motivated to live and work across this transformative region, which included the area from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River and beyond.

In times of warfare, the frontier played an essential role in American victory, but conflict there was vastly different than the traditional battles fought near strategic centers of gravity. Typically, war on the frontier consisted of irregular combat, marked by local resistance and irregular strategies and tactics, as well as guerrilla troops.

These guerrillas fought using nontraditional combat methods. Their small-unit tactics and understanding of local terrain and communities gave them an advantage that ultimately made up for the superior numbers of their enemy. However, with the guerrilla war much closer to home and hearth for these rural settlers, society and ideology on the frontier were torn apart within a short period of time. With the line between combatants and civilians blurred, war crimes helped consistently fuel the irregular units resisting the enemy. The increase in resistance by local combatants, who understood the local geography and population, gave the irregulars a significant advantage over their enemy.

As the new country approached the 80th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, it rapidly degenerated into armed conflict over the divisive issue of slavery’s expansion westward. This outbreak of violence was concentrated along the border of Missouri and the Kansas Territory, giving the period the notorious name of “Bleeding Kansas.”

At that time, pro-slavery and abolitionist irregular fighters each took the law into their own hands, with the hope of impacting the statehood election for the Kansas Territory. By targeting the homes and communities of their rival faction, these vigilantes set the tone of warfare on the border for the next two decades, and escalated the level of violence by the time civil war erupted in 1861. Many rural border communities — like Lawrence and Osawatomie — were the sites of horrific massacres between the two factions in these pre-Civil War days. Such feats were only feasible through an undeniable attention to terrain and intelligence. By 1861, however, the Border War — defined by guerrilla warfare — deteriorated into a brutal, seemingly unending conflict for those on the frontier.

A Tradition of Irregular Operations

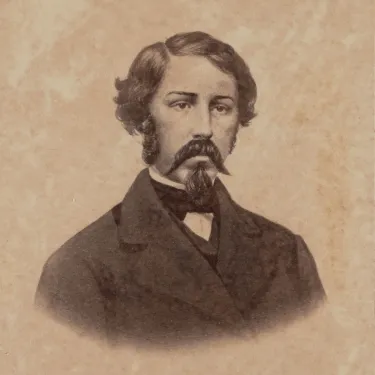

On September 23, 1861, James H. Lane, a U.S. senator from Kansas and future Union brigadier general, led his 1,200-man brigade of Jayhawkers across the border into Missouri and ransacked, plundered and burned the town of Osceola. Two months later, when the pro-Confederate Missouri State Guard entered town, one member, John W. Fisher, reflected, “It is enough to make a man’s blood boil … Men are anxious to go to Kansas and retaliate.”

The aggressive and infamous Col. Charles “Doc” Jennison also continued his jay hawking war against Missouri by forming the 7th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, known as “Jennison’s Jayhawkers.” The numerous attacks by Jayhawkers turned even more Missourians against them, which soon led to the formation of the infamous Quantrill’s Raiders, named after the unit’s commander and namesake Capt. William Quantrill.

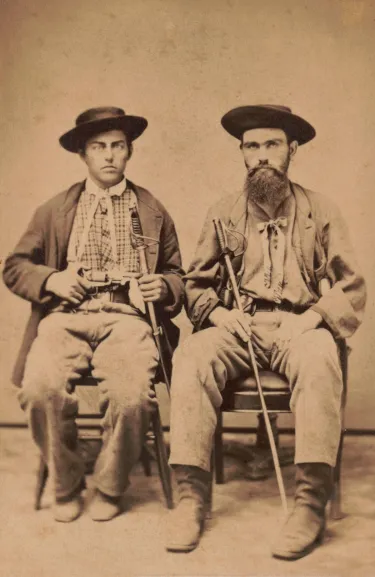

Quantrill’s Raiders, also known simply as the Missouri Guerrillas, were fueled by personal desire for revenge against Kansans, Jayhawkers, Union troopers and authority more broadly. Each member was a local citizen of Missouri’s Western Border and had personally experienced the wrath of the Border War, which allowed them to familiarize themselves with their area of operations. In fact, many were Missourians who had fled into the brush to fight Union authorities through ambushes, harassment, robberies and hit-and-run attacks.

In this, they were following in the footsteps of other American forces who had fought on the periphery of earlier conflicts, including the Revolutionary War Overmountain Men of Appalachia, who traversed hard country to triumph at the Battle of King’s Mountain. They also echoed the South Carolina Low Country irregulars under the “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion. Missouri Guerrillas strategically utilized the area they knew so well by relying on loyal civilians, lesser-used roads and trails and creeks to remain concealed and move throughout both Missouri and Kansas undetected. In fact, the Missourians’ guerrilla-like tactics and firm understanding of the terrain around them led to their infamous nickname, the “Bushwhackers,” as they seemed to blend into the landscape itself, evading capture.

Bushwhacker Country

There are countless examples of the Bushwhackers utilizing their local knowledge of their area of operations, including a raid on Olathe that was one of their greatest victories early in the war. Because of their “ravines, hills, and hollows,” as well as their infestation of creepy critters, the Sniabar Hills of the western Missouri backcountry were Quantrill’s preferred hideout location — and a place no Federal trooper dared to enter. In the late evening of September 6, 1862, the Bushwhackers moved west through the “Sni” and crossed the border into Kansas completely undetected by Federals. Swiftly and quietly, they moved through eastern Kansas and captured three Jayhawkers. Entering their camp, the Guerrillas dragged the Jayhawkers from their beds and murdered them. Their knowledge of the land and their quick movements allowed them to advance straight into the Kansas town of Olathe, which they soon ransacked and plundered. As one Kansas soldier wrote about Quantrill’s men after that raid, “They were familiar with every cow-path, knew every farmer.”

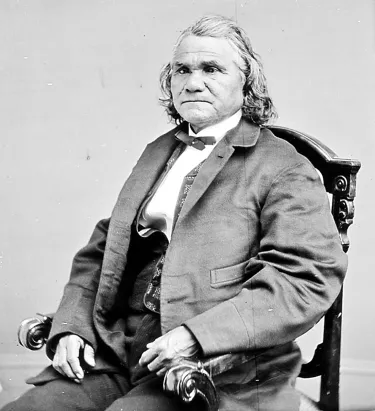

Numerous bands of irregulars operated across Missouri, and these smaller units also resisted Union occupation. Early in the war, Brig. Gen. Meriwether Jeff Thompson commanded the First Division of the Missouri State Guard, which was based out of the southeastern “Bootheel” region of the state. Unable to join the main body, the unit remained in its home area and exploited the Bootheel extensive swamps to its advantage. Like Quantrill’s Raiders and the Kansas Jayhawkers, Thompson’s men were locals who knew the swamps and region very well. Their repeated success in using the swamps to surprise Federal troops led to their commander’s legendary nickname: the “Swamp Fox of the Confederacy” in tribute to Marion.

In the fall of 1861, Brig. Gen. Ulysses Grant, commander of the District of Southeast Missouri, was repeatedly forced to deal with the nuisance of Thompson’s men. On October 2, 1861, Grant deployed more than 1,000 men to intercept these irregulars, but they remained elusive. It was not until later that month, when the irregulars were far north of their native “Bootheel” region and completely outnumbered, that Thompson was defeated.

Native American Units

Also utilizing local knowledge to their advantage were the Confederate units of the Five Civilized Tribes. Though the First and Second Cherokee Mounted Rifles are the most well-known of the units — and Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, the most well-known Native American Confederate general — there were units from each of the five tribes: Cherokee, Seminole, Choctaw, Creek and Chickasaw. Like many other Confederate units on the frontier, these Native American units did not venture far from familiar areas, operating primarily within their own territories in present-day Oklahoma or using these areas as launch points to conduct partisan operations.

The Native American mounted infantry and cavalry regiments’ irregular style of warfare bore fruit in their 1864 raids into Kansas and Missouri, and the successful capture of Federal supplies at Cabin Creek. At the Second Battle of Cabin Creek on September 19, 1864, Confederate Choctaw and Cherokee troopers united in attacking a Federal wagon train filled with more than $1 million-worth of supplies. Their success was part of a larger effort of raiding Federal supplies throughout the Indian Territory and Kansas, a result of the Cherokee Nation’s remarkable knowledge of the region’s geography and rail systems. It was one example of the Cherokee Nation’s successful exploitation of the advantage offered by operating within its own territory.

The American Civil War may have lasted four bloody years, but the war between Rebel irregulars and Union authorities continued far longer than anyone could have imagined. For years after the Civil War, many of these frontier irregulars continued their personal war against authority, as seen with the James and Younger Brothers. Indeed, the strategies of the guerrilla fighters on and off the battlefield have been at the center of American military strategy due to the military’s increasing interest in counterinsurgency operations. Since before the country’s entry into the War on Terror in 2001, the American military has studied frontier irregulars like Quantrill, Jennison, Lane, Thompson and Watie to learn how best to fight modern-day terrorists. Simultaneously adored and despised, but universally respected, these frontier irregular fighters from the Civil War — through their use of geography, terrain, civilians and small unit tactics — have shaped the way the United States has waged war ever since.