At the outset of the Civil War, it was immediately clear that the mapping resources available to commanders on both sides were woefully insufficient. In most cases, state legislatures issued medium-format maps of their territories at a scale of five miles to one inch, meaning they lacked necessary detail. Moreover, although they had been updated by state governments in the 1850s, the base maps might be decades old; the state maps of Maryland and Virginia — the most likely theater of war, given the location of the warring sides’ capitals at Richmond and Washington, D.C. — originally dated to 1841 and 1826, respectively.

Commercially produced county-level maps, often at the far better scale of one inch to a mile, were snatched up by commanders whenever the opportunity presented itself, including through confiscation or subterfuge, as the Confederate army did when it plotted its 1863 invasion of Pennsylvania.

Despite the lack of existing maps that plagued both sides, the Union war effort was at a material advantage, in that it had infrastructure in place that could be mustered toward the challenge. Swiftly, the U.S. Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers and Corps of Engineers, the Treasury Department’s Coast Survey and the navy’s Hydrographic Office took on greater roles and significance than ever before. Under the direction of Maj. Gen. John G. Barnard — ultimately the chief engineer for all Union armies in the field — maps of unprecedented detail were produced for the region around Washington, D.C., to aid in its defenses. As mapping projects moved into Virginia and other enemy territories, professional survey and reconnaissance teams from the various branches worked cooperatively to inform precise finished products for both land and naval operations.

Reconnaissance and Rendering

Unable to rely on existing entities in the way their counterparts in Washington were, authorities in Richmond faced a very serious quandary with regard to mapping. Describing the untenable situation faced by his fellows during the Seven Days’ Battles of 1862, Confederate Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor recalled, “The Confederate commanders knew no more about the topography of the country than they did about Central Africa.” Assuming command of the Army of Northern Virginia in the midst of the campaign, Gen. Robert E. Lee, who had been trained as a military engineer, swiftly set about rectifying the situation, appointing a new head of the Topographical Department five days into his tenure and sending field parties out almost immediately.

Perhaps, then, it is unsurprising that the most famous Confederate mapmaker of the war — Jedediah Hotchkiss, whom Stonewall Jackson famously commanded to “Make me a map of the Valley” — was a schoolteacher by trade and had no formal cartographic training. Instead, it was his keen observation and survey work in the field that bred success.

As any army moved through the field, topographical engineers and cartographers were forced to keep pace, often working under pressure to provide maps on short notice in a variety of formats. For example, maps rendered on washable muslin were particularly sought after by the cavalry, as they could survive hard service. Areas of repeated campaigning became increasingly well mapped, but when a force prepared to launch an incursion into new territory, fresh challenges presented themselves.

Take the Atlanta Campaign, when Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s command was operating so far from Washington that it was forced to put into place mechanisms and staff not only to research and construct maps, but also to print and distribute them. To craft useful and usable maps for the army, engineers began by taking the best available map and enlarging it proportionally via the scale. Then came critical additions made via any and all means of intelligence possible, including engineers’ own expeditions into the field, other spies and scouts, refugees and local civilians and prisoners of war. In his History of the Army of the Cumberland, Thomas B. Van Horne recalled that “the best illustration of the value of this method is the fact that Snake Creek Gap, through which our whole army turned the strong positions at Dalton and Buzzard Roost Gap, was not to be found on any printed map that we could get” but was attested to by those with local knowledge.

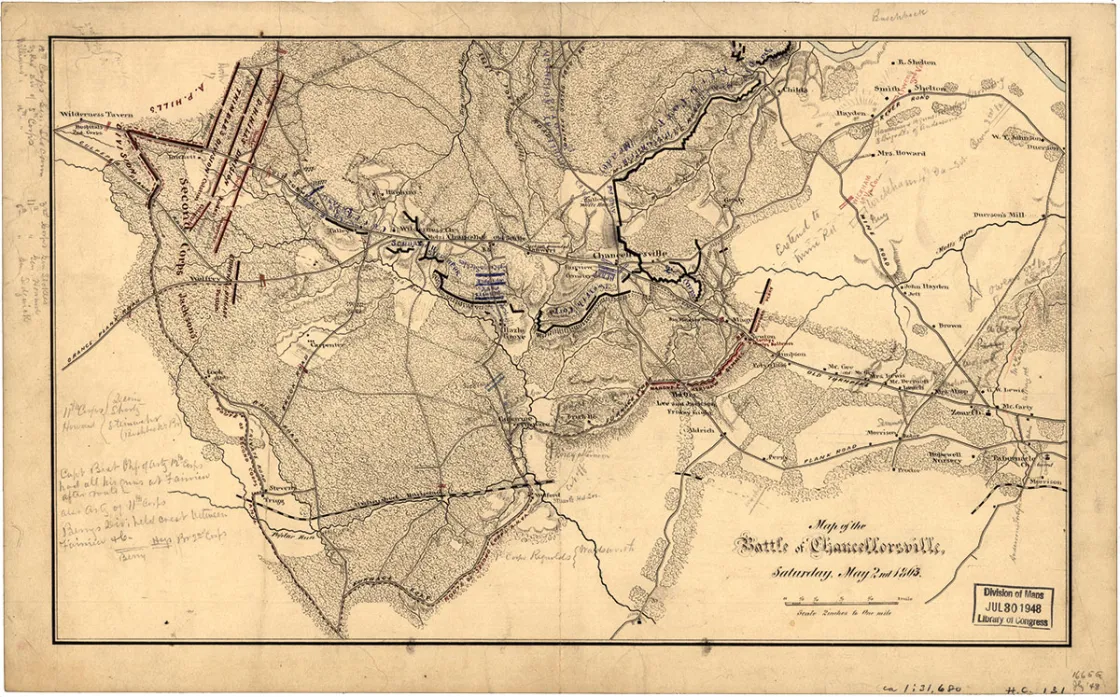

When they were not busy producing new maps for every brigade commander and higher officer — reproduced in sections to be of manageable size when folded, and mounted with cardboard covers to protect the valuable document from the elements — topographical engineers were further tasked with creating accurate maps of the action that took place during battles. Engineers were issued small-scale maps when they made field reconnaissance alongside the army, marking additional features and positions as they encountered them. These data could then be integrated into updated regional maps, as well as maps made to record instances of combat that were filed with official reports.

After the war, these cartographical resources created by both Northern and Southern armies were consulted for the U.S. War Department’s Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. This monumental undertaking is remarkably thorough and, with 178 plates of images, remains the most detailed atlas of the Civil War — a resource still reprinted in new editions and consulted by historians of all stripes.

Printing and Reproduction

As important as thorough reconnaissance of terrain and accurate recording of these details onto an authoritative map may be, it is just as critical to sufficiently reproduce and distribute that information.

The tried-and-true method for mass production of maps in the field, used for centuries after Johannes Gutenberg debuted his groundbreaking technology, was transferring the information onto a copper engraving and using a traditional printing press. The process required significant time and skill, as well as a steady hand and the patience to engrave an entire map in reverse.

Then, in the 19th century, the reproduction process was revolutionized with the advent of lithographic printing, which enabled significantly more detail to be included and expedited the process. The desired images were drawn, in reverse, onto large, flat slabs of limestone and then chemically etched so that ink could be applied. When care was taken to line them up properly, multiple stones could be prepared for layering colors to better convey detailed information, approximating the delicate watercolors employed on the originals.

Refinements to the process came with the advent of the transfer method, which allowed cartographers to draw their work in the “positive” on pretreated paper that could, through chemical reactions, transfer the image onto stone. In either case, lithographic printing was speedier and more forgiving than printing from plated engravings, but it required cumbersome equipment — large presses and heavy stones. Still, many topographical engineering units maintained both options in their headquarters.

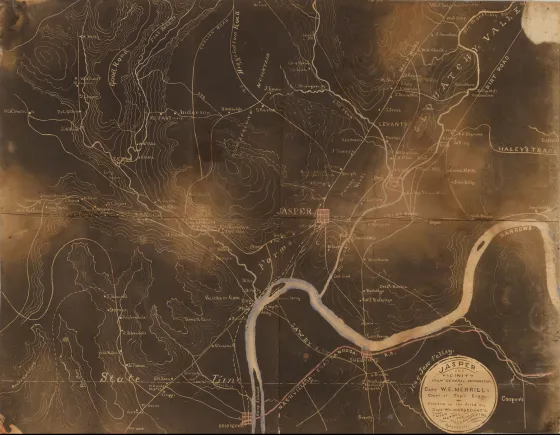

During the Civil War, however, another technological advance — photography — offered tantalizing promise as a way to efficiently reproduce maps for distribution. Photographic techniques of the time allowed images to be captured in great detail on large glass plates. Multiple prints could be made on paper treated with a solution of dissolved table salt using the same plate. But, as with any emerging technology, the price was steep, and printing results required significant refinement. According to a report by Capt. W. E. Merrill of the federal Army of the Cumberland, early-war prints were suboptimal on several counts: the borders might distort and sections not join properly, prints were prone to fading in sunlight and the process itself was weather-dependent.

Capt. William Margedant of the 9th Ohio, who had worked in photography before the war, developed a groundbreaking technique for map reproduction. His “black maps” — named so because the information appeared in white on a black background — were swift to reproduce, meaning that amended versions could be distributed as new information was gathered. Equipment requirements were minimal and eminently portable, albeit expensive. This technique was used to great effect in the later part of the war, particularly in the Western Theater.