Slaughter Pen Farm, Fredericksburg Battlefield, Va.

Fredericksburg, December 1862

Has Google Maps ever led you astray at work? Your boss describes your destination for the big meeting as one place, but Google Maps tells you something else entirely? And it always happens at the worst possible moment. There is, perhaps, no better example of the 19th-century version of Google Maps setting an army on the wrong path than the Battle of Fredericksburg.

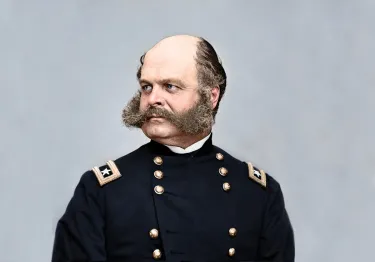

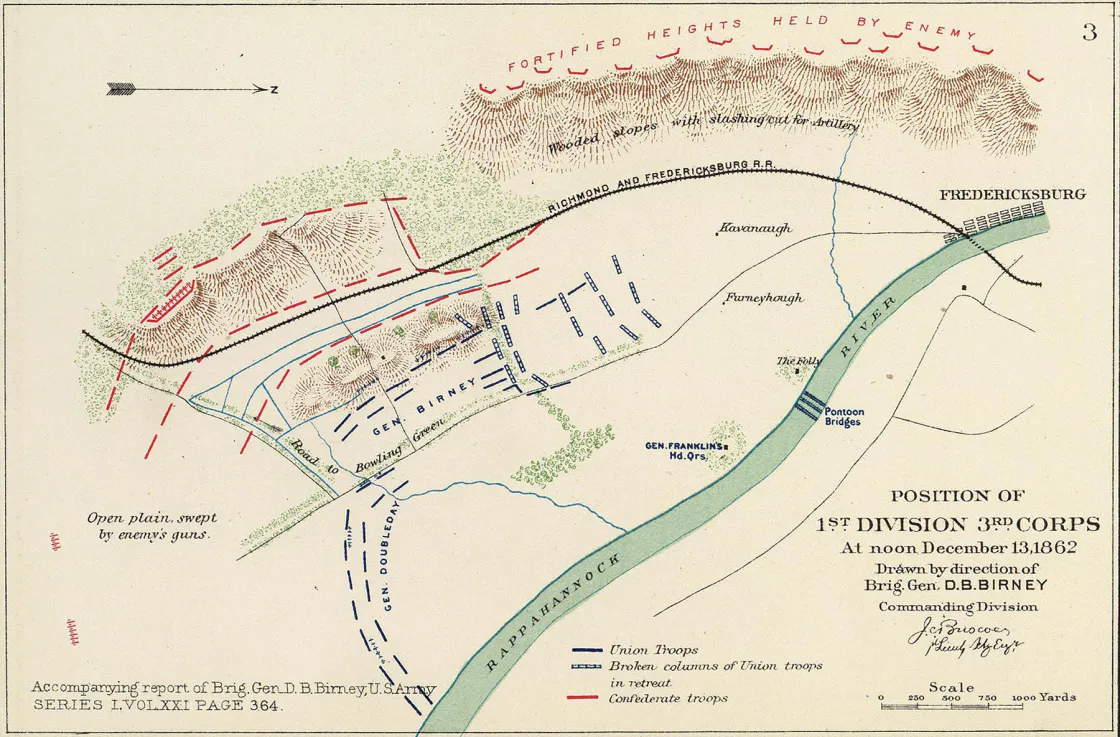

On the morning of December 13, 1862, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside set into motion a two-pronged assault against the Confederate lines. The northern prong targeted the now infamous Marye’s Heights sector. The southern prong, Burnside’s more powerful thrust, targeted the “the heights near Captain Hamilton’s.”

Some 60,000 Federal soldiers stood poised to “seize” the heights. The commanding general’s orders seemed clear, at least to him. Left Grand Division commander Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin was “to send at once a column of attack … composed of a division at least, in the lead, well supported and to keep his whole command in readiness to move down the old Richmond road.” Burnside hoped that Franklin’s men would get “in the rear of the enemy’s line on the crest.”

Thus, Old Burn thought that he had just ordered one-half of his army to attack and cut off the Confederate left flank from its direct line of retreat to Richmond. There were two major flaws in Burnside’s plan, however. The first was that he used an incorrect term in his orders. He should have ordered Franklin to “carry” the heights, not “seize” the heights. The former term carries more weight in military parlance. The second flaw was with Burnside’s map of the battlefield.

The high command’s map showed the Old Richmond Stage Road running parallel to the Rappahannonck River. Which it does. But, Burnside’s map also showed the road taking a sharp, 90-degree turn westward about two miles south of the city. This abrupt turn should have led the Federals toward the enemy, the heights and their objective. Sadly for the Federals, the road did no such thing: Their map was utterly incorrect.

Instead, the road meandered south, away from the Confederate position, rather than decisively turning west. Franklin, who was stationed on the west bank of the river, knew that the road actually led away from the Confederate position. But rather than being proactive and asking his commanding officer for clarification, Franklin blindly followed his orders. Baffled as to why Burnside would order his men due south, Franklin just assumed that his wing would not spearhead the major Federal offensive as had been outlined the night before in a meeting of senior officers.

Instead, Franklin halfheartedly attacked. His blind obedience and an inaccurate map led to one of the worst defeats in the history of the Army of the Potomac, including a needless bloodbath at Marye’s Heights.

Spotsylvania Court House, May 1864

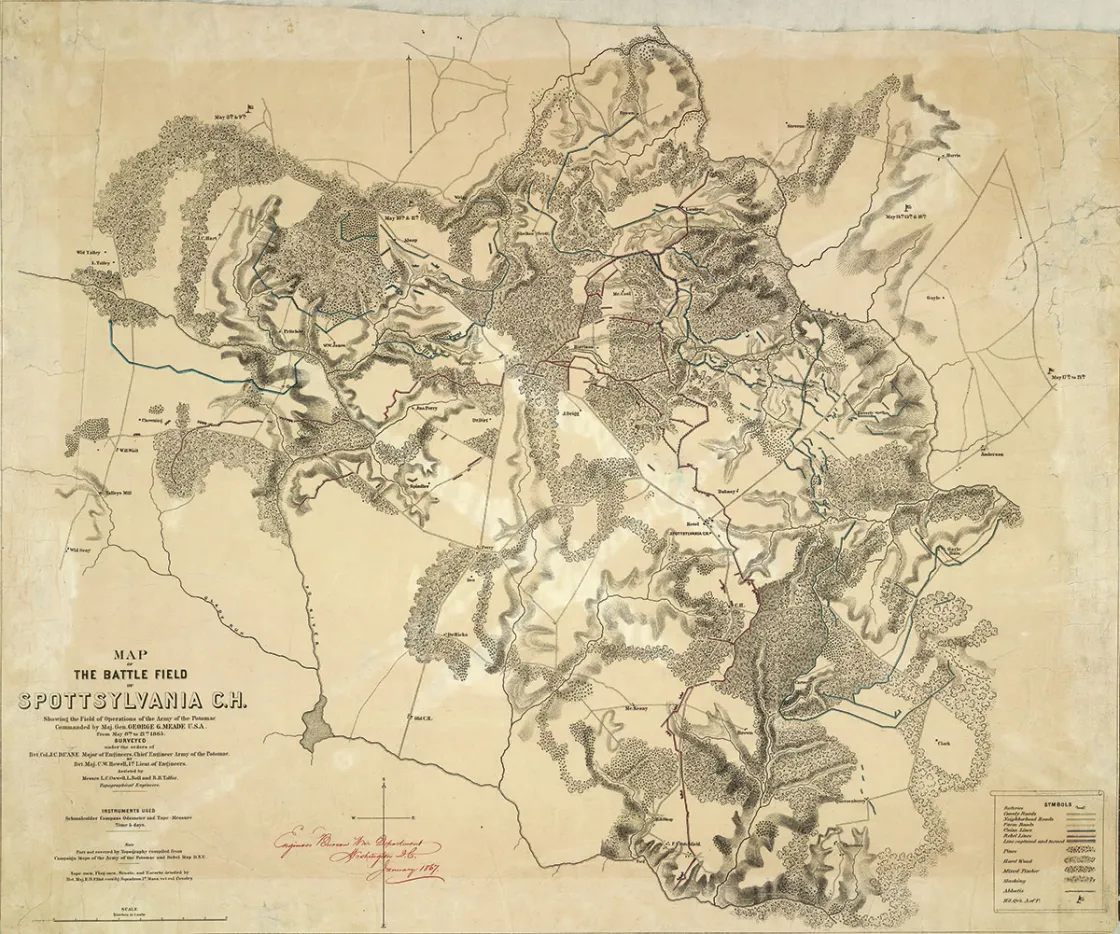

Proper maps and the identification of critical landmarks are vital to a commander. An erroneous map, remembered Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, an aide de camp to Maj. Gen. George Meade, could “utterly bewilder and discourage the officers who used it, and who spent precious time in trying to understand the incomprehensible.” Plagued by faulty maps, the Union army barely averted catastrophe in the opening days of the Overland Campaign.

Following a two-day stalemate in the Wilderness, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered Meade’s Army of the Potomac to Spotsylvania Court House. Grant hoped to reach the crossroads and seize the inside route to Richmond ahead of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. While the bulk of the army moved along a north-south axis, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps was to march east through Chancellorsville and then proceed to Spotsylvania via the Fredericksburg Road. Grant directed Burnside not to advance farther than an area identified as the “Gate” on a headquarters map. Unfortunately, the landmark did not appear on the map in Burnside’s possession.

Once again, Burnside fell victim to poor and inaccurate maps. The same obstacle led to a misunderstanding when, at the head of the Army of the Potomac during the Battle of Fredericksburg, he issued orders to his subordinates based on faulty understanding of the terrain, contributing to the devastating Union defeat. Removed from command and relegated to lead a corps instead of an army, Burnside now found himself on the receiving end of a similar situation.

On the morning of May 9, 1864, one of Burnside’s divisions, under Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox, reached a driveway leading to the Gayle House, some four miles northeast of Spotsylvania. Willcox believed he had reached the “Gate” indicated by Grant, when, in fact, he was well south of the actual location. Unknowingly in the wrong place, Willcox was soon drawn into an engagement.

Directly to his front and across the Ni River were troopers from Brig. Gen. Williams C. Wickham’s Confederate cavalry brigade. Rather than hold his position, Willcox pushed forward regiments from Col. Benjamin Christ’s brigade. Christ’s men drove off Wickham’s troopers and took control of the south bank.

As other brigades crossed, Willcox placed himself in a precarious position. His was Burnside’s only division over the Ni River. Without support, Willcox was isolated and vulnerable to an assault. Later that day, Brig. Gen. Robert Johnston’s North Carolinians attacked Willcox. Although the assault was initially successful, Willcox rallied and repelled his attackers. The destruction of an entire division would have seriously impacted the Union army during this critical juncture in the campaign. And the situation would have been made worse by the knowledge that the outcome had been avoidable, if only the high command had possessed accurate maps.