Cedar Creek: Then & Now

The Civil War Trust sat down with park historian Eric Campbell to discuss this important Shenandoah Valley battle.

Civil War Trust: Set the stage for us. Where does Cedar Creek fit into the overall picture of the war in the east?

Eric Cambell: With the Army of Northern Virginia pinned to the entrenchments of Richmond and Petersburg and slowly dwindling away, Robert E. Lee was desperate for some type of victory that might reverse Confederate fortunes and possibly influence the outcome of the upcoming presidential election in early November. Unable to maneuver his own army without risking the fall of the Confederate capitol, it seemed that Lee’s only real choice was Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Army of the Valley in the Shenandoah. Of course, even that appeared impossible, as Early’s forces had recently been defeated in a series of battles by Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah in September and early October (3rd Winchester, Fisher’s Hill and Tom’s Brook). Following those disasters, and to add insult to injury, Early’s men had little choice but to watch helplessly as the Union army then systematically destroyed the Valley’s agricultural resources during a two-week period know since simply as “The Burning.”

From all appearances then, in early October, 1864 Early’s army was defeated and the campaign in the Shenandoah Valley was over. To the Union high command it was simply a matter of what should be done with Sheridan’s forces? For Robert E. Lee, however, the Valley offered his only real hope. Therefore, in addition to sending 3,000 more men from his already beleaguered army at Richmond, Lee urged is Valley commander to make one more effort to regain the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy.”

Although he had almost 2-to-1 odds against him, Early ordered one of the most risky and audacious attacks attempted during the Civil War. It was a tremendous gamble, which ultimately came very close to succeeding.

Can you compare and contrast the two armies and the two commanders?

EC: The Union Army of the Shenandoah numbered approximately 32,000 officers and men at Cedar Creek and was organized into three infantry corps (Sixth, Eighth and Nineteenth) and three divisions of cavalry. All of these soldiers were veterans before the 1864 Valley Campaign, but were only fighting together as an army for the first time.

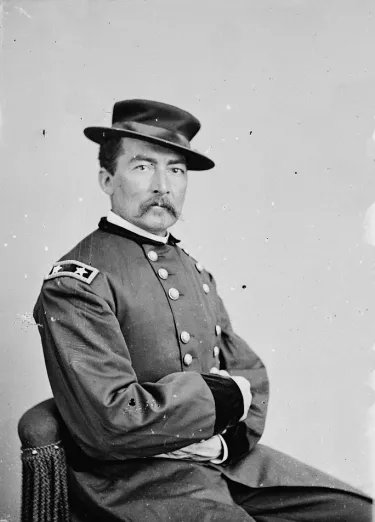

When U.S. Grant picked Sheridan to command all of the Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley that August, it became his responsibility to merge these divergent units together into an efficient army. Being only 33, and never having held an independent command, many (including Abraham Lincoln) doubted whether Sheridan was the right choice. Although it took him over a month to organize the Army of the Shenandoah, the subsequent results of the campaign proved that Sheridan was more than capable of commanding an army.

Although small in stature (5’5”) Sheridan more than made up for his size in personal leadership and courage. When he took command of the army even much of the rank-and-file doubted his ability. It soon became evident; however, that their new commander knew what he was doing, could lead men in battle, and always seemed to look out for their best welfare. By the end of the campaign, especially following the morning disaster at Cedar Creek, the mere sight of “Little Phil” could, and did, instantly lift his men’s morale.

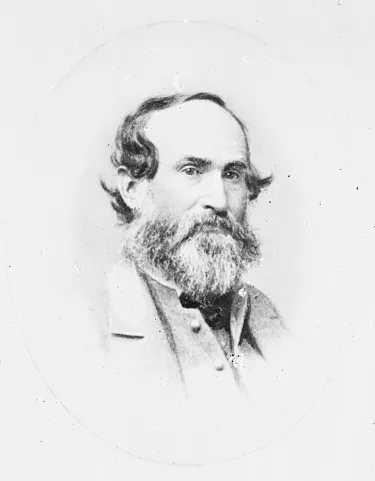

At 47, Jubal Anderson Early (“Old Jube” to his men) was older than his Union counterpart at Cedar Creek, although arthritis and his graying beard made him appear even older. He was also a more experienced commander. Early took command of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Second Corps in the midst of the Overland Campaign in May, 1864 and led it into the Valley as an independent command just one month later. By mid-July Early and his men were on the outskirts of Washington, DC. It was this raid, of course, that eventually brought Sheridan and most of his troops to the Valley that August. Overall, Early was an excellent commander. Preeminent southern historian Douglas Southall Freeman considered him to be “second only to Jackson himself.”

Early’s Army of the Valley consisted mostly of his own Second Corps, supplemented by various units that were attached to it throughout the campaign. Although battle-tested and hardened veterans, these Southern soldiers faced long odds during the Valley Campaign. Constantly under-supplied and ill-fed, they also were constantly outnumbered by their opponent. At Cedar Creek they only numbered around 14,000. Yet, through it all these men followed their hard-bitten commander to Cedar Creek, and to the verge of an incredible victory during the morning hours of October 19, 1864.

What is Cedar Creek like? What are some of the terrain features and how did they affect the campaign and battle?

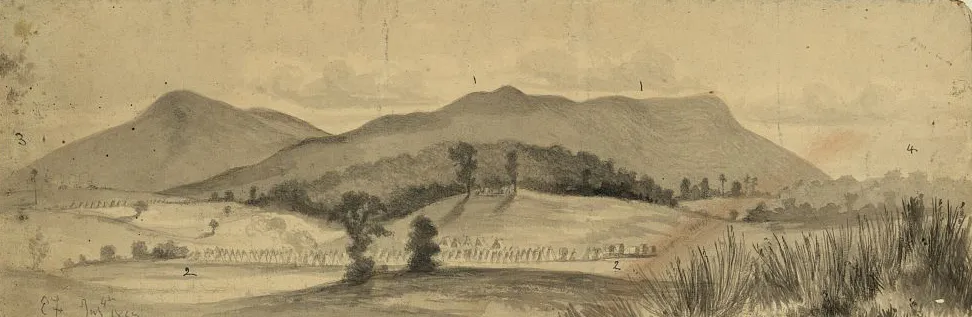

EC: Located in the Lower Shenandoah Valley, the Cedar Creek battlefield lies within three counties (Frederick, Warren and Shenandoah) and in the shadow of the most prominent terrain feature associated with the battle; Signal Knob, the highest peak on the northern end of the Massanutten Mountain. Signal Knob played a central role in the events leading up to the battle, for it was from that peak that several Confederate officers (among them Maj. Gen. John Gordon and Maj. Jedediah Hotchkiss) scouted the Union army on October 17, and created their bold attack plan which worked so successfully two days later.

The battlefield itself is a long, yet narrow corridor that runs southwest to northeast, from Strasburg to Middletown, and to the rolling fields beyond. Bisecting the axis of this corridor was the macadamized Valley Pike (modern U.S. Route 11), which had to be held by the Union army, as it was their principal line of communication, supply and possible retreat. The battle’s namesake is, of course, Cedar Creek, which cuts a torturous twisting route through the south-central section of the battlefield before emptying into the North Fork of the Shenandoah River at the base of the Massanutten, along the battlefield’s southeast corner.

From Signal Knob, Gen. John B. Gordon spotted a narrow avenue of approach along the base of the Massanutten which would allow nearly half of the Confederate army to position itself opposite the Union left and rear. The approach march itself was made by three divisions (approximately 6,000 men) under Gordon, and was conducted on the night of October 18-19. The route was approximately 8 miles long and involved two crossings of the waist deep Shenandoah River. Adding to the difficulty was that the path at the base of the Massanutten was so narrow and rutted in that the men referred to it as a “pig path” and they had to pass along sections of it in single file. Lastly, upmost silence had to be maintained in order to conceal their approach. Despite all of these difficulties, Gordon was able put his men into position just before dawn on October 19. Completing their surprise was a dense fog that settled over the area just before first light.

It seems that the Confederates were all but counted out at this point. Why?

EC: As I stated before, because of the earlier, almost crushing defeats Early had suffered in the Valley (at 3rd Winchester, Fisher’s Hill and Tom’s Brook), it appeared that the Valley Campaign was over and that the Confederate Army of the Valley was finished as a fighting force. Besides being outnumbered over 2 to 1, Early’s men were also poorly equipped, clothed and supplied and, with “The Burning” devastating the Valley’s rich agricultural resources, they had no hope of supplying or feeding themselves off the land. Indeed, the Confederate cause in the Valley seemed hopeless.

It was natural for the Union leadership (and rank-and-file) to assume that the Confederates were also demoralized and therefore poised no real threat. This situation made it easy for Philip Sheridan to leave his army on October 15 for a council of war with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and others in the Union high command in Washington, DC. Sheridan left the army in the capable hands of Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright with no fear that anything of significance would happen before his return.

What was General Early’s main goal at Cedar Creek? Was he only delaying the inevitable?

EC: At its simplest, Early’s main goal was to crush Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah and send it reeling northward to the Potomac River and thus out of the Valley. Early was attempting to inflict a crushing defeat on his enemy in order to regain the Valley for the Confederacy. This in turn might cost Abraham Lincoln the election in November. A victory by a Peace Democrat at the polls, of course, could possibly result in a political settlement and ultimately Confederate independence.

If nothing else, Early felt that at least achieving a partial victory at Cedar Creek (say, causing the Union army to retreat to Winchester or beyond) would pin down Sheridan’s forces in the Valley for the remainder of the year. Lee was urging Early to make another attack, not only to regain the Valley, but also to prevent the bulk of Sheridan’s forces from being sent to reinforce Grant at Richmond and Petersburg.

As we look back on these events with perfect hindsight, it seems to us that Early was simply delaying the inevitable. But at the time, it was the hope of both Lee and Early that a major Confederate victory in the Valley could have significant military and political benefits.

To think today that these hopes were unrealistic is oversimplifying the historic facts. As an example, I think the only thing that kept the Union army from conducting a full-scale retreat to Winchester following their defeat that morning was the arrival of Sheridan on the battlefield. Without Sheridan’s presence on the field, which instantly restored the army’s morale, and his insistence on maintaining the field and launching a counterattack that afternoon, Cedar Creek would have gone down in history as a significant Confederate victory.

Why are the deeds of the 8th Vermont memorialized on the field? What did they do?

EC: Unlike many other Civil War battlefields, which are marked by numerous memorials, the Cedar Creek battlefield only has three monuments. One of those is dedicated to the officers and men who served in the 8th Vermont, who fought on the very ground which the Civil War Trust is preserving. The reason this regiment has a monument on the field is due to one of its members, Herbert Hill, who was an 18 year-old private when he fought at Cedar Creek. A successful business man after the war, Hill decided to commemorate the deeds of his fellow soldiers in the Valley by personally paying for the creation and placement of two monuments in 1885; one at Cedar Creek and the other at 3rd Winchester (this monument was later moved to the Winchester National Cemetery).

The 8th Vermont belonged to Col. Stephen Thomas’s brigade (approximately 1,500 strong) which was ordered into the maelstrom of the overwhelming Confederate attack that had just shattered the 8th Corps and crushed the left wing of the army. Essentially Thomas’s brigade was sacrificed in order to buy time for the rest of the Union army to retreat and reposition itself against the crushing Confederate advance. In a desperate stand that lasted about 30 minutes, the brigade was decimated, losing over 70 percent of its strength before being overwhelmed and swept aside. The 8th Vermont lost 110 killed, wounded and captured out of its 164 officers and men (68 percent casualties). The monument marks one of the most famous incidents of the battle, being located on the spot where a tenacious struggle for the regiment’s two flags occurred, and where three of its color-bearers were killed defending them. Ultimately, though forced to withdraw, the flags were saved.

What does the word Rienzi mean and why is there a knoll named as such?

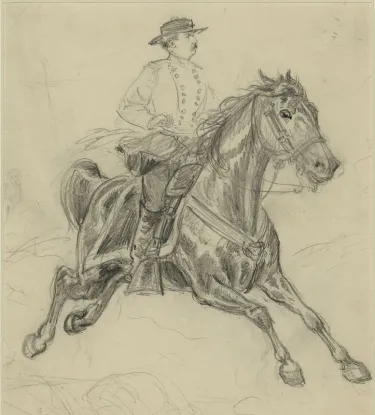

EC: Rienzi was Gen. Sheridan’s favorite horse, a large black gelding, which he rode the morning of the battle from Winchester to Middletown. Sheridan acquired the steed in 1862 when he was stationed near Rienzi, Mississippi. The general rode Rienzi throughout the war, including 19 battles and dozens of smaller actions. Although the horse survived, it was wounded numerous times.

On October 18, having just returned to the Valley from a council of war in Washington, DC, Sheridan spent the night in Winchester. His plan was to return to his army the next day, October 19. Of course, believing the Valley campaign was over, the last thing Sheridan expected was a battle. Even when he began to ride up the Valley Pike that morning, Sheridan had no idea that his army was at that moment fighting for its very existence. Upon hearing the distant sounds of artillery, however, and then soon after hearing the rumors of a major battle, Sheridan began to quicken his pace back to his army. Thus began one of the most famous incidents of the battle, “Sheridan’s Ride.”

This incident was later made famous in both art and poetry. The poem, “Sheridan’s Ride” was created shortly after the battle by Thomas Buchanan Read, and eventually became one of the most widely read poems in the country, being a favorite regularly recited by Northern school children for decades after the war. The poem vividly recounts Sheridan’s ride and its impact on the outcome of the battle, but ironically concentrates as much on Rienzi’s role in the event as it does Sheridan’s deeds.

When Sheridan reached the battlefield around 10:30 a.m. he caught the first glimpse of his defeated army from a knoll 1 ½ miles north of Middletown. Despite the shock, Sheridan instantly began to take steps to restore his troop’s morale, reorganize their lines and plan a counterattack in order to reverse the monumental defeat that his army had suffered. Today, this small rise is known as Rienzi’s Knoll, to commemorate the events that took place on its slopes that fateful October morning in 1864.

What entities are active in the preservation and partnership at Cedar Creek?

EC: The preservation efforts at Cedar Creek are exactly that, a partnership. Long before the arrival of the National Park Service in 2002 (with the creation of Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park) there were already several groups already engaged in preserving the battlefield and other historic resources associated with the area. These groups, all non-profit organizations, included the Cedar Creek Battlefield Foundation, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Belle Grove, Inc., the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, and Shenandoah County. Combined, these organizations, all of which are self-sustaining, have preserved over 1,500 acres at Cedar Creek. When the idea of creating a national park in the Shenandoah Valley began, these groups not only became willing partners, but it was due to their efforts that the park was finally approved. Simply put, the national park at Cedar Creek would not exist without these organizations.

These groups are now considered the Key Partners, who work in cooperation with the National Park Service , to preserve and manage the cultural resources of the park, and to interpret the many events related to not only the battle, but also the rich history of the Valley, from pre-settlement through the Civil War and beyond.

How can a visitor tour Cedar Creek today?

EC: While the park has existed since 2002, it has only recently that the National Park Service has started limited interpretive operations. Beginning in the summer of 2010, NPS staff has offered regularly scheduled interpretive programs. These occur daily in the summer, and on the weekends in the spring and fall, at various Key Partners sites.

One of these programs is a ranger-conducted car caravan “Battle of Cedar Creek Tour” of the battlefield (visitors follow the ranger’s vehicle). This two-hour, 13 mile tour covers the battle chronologically and includes 6 or 7 stops at key locations. All of the ranger program and times are listed park website.

Visitors can also tour the battlefield on their own, using a couple of different methods. The NPS, in partnership with civilwartraveler.com created a free podcast tour, which can be downloaded off the park website (and includes a map and driving directions). A self-guided tour brochure is also in development and will be available soon.

Self-guided tour booklets of the battlefield are also for sale at the Key Partners sites. And, of course, the Civil War Trust will soon release a free Battle App of Cedar Creek which will allow visitors to tour the field on their own.

Keep in mind, however, that unlike established national parks, Cedar Creek and Belle Grove NHP is a park-in-development, which means it currently contains very little infrastructure (park signage, wayside pull-offs or signs, trails, etc.). Nearly all of these tour options use public roads to allow visitors to see the field. Although over 1,500 acres of the battlefield is preserved by the Key Partners, most of this land is still inaccessible to the public. The remaining property within the park boundary is still privately owned.

How well preserved is the Cedar Creek Battlefield?

EC: While over 1,500 acres of the battlefield has been preserved, the park’s authorized boundary contains nearly 3,700 acres. Furthermore, the actual battlefield extends beyond the legislated boundary. The good news is that the majority of the land that has been preserved has been saved within the last 20 years. Thus, while great strides have been made in the last two decades, much work remains to be done.

The Cedar Creek battlefield faces numerous threats, including the expansion of a nearby industrial limestone quarry operation, the potential widening of Interstate 81 (which cuts the battlefield in two), and the always present threat of commercial and residential development (and not just on the edges of the battlefield, but throughout the heart of the park itself).

Do you have a favorite story associated with the Battle of Cedar Creek?

EC: There are numerous intriguing stories associated with the battle. Most of the ones I find fascinating are the same which I related in the answers to the questions above. Certainly “Sheridan’s Ride” and his personal impact on the outcome of the battle (literally snatching a victory from the jaws of defeat) is one of the most interesting. The story of the sacrifice of the 8th Vermont, and the fellow regiments in Col. Thomas’ brigade, is also worthy of study and remembrance. I also find the Confederate attack plan, including its incredibly risky and difficult approach march, extremely fascinating. Despite the overwhelming odds against them, I think Early’s men came very close to achieving the victory they sought at Cedar Creek.

Finally, individual stories of soldiers and their sacrifices are also intriguing. A good example at Cedar Creek, of course, would be that of Maj. Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur, whose young wife had just delivered their first child shortly before the battle. Hoping to achieve a victory at Cedar Creek so that he could earn a furlough home to see his wife and child, Ramseur instead was mortally wounded during the battle and died at Belle Grove the next day. Thus his wife was left a widow, and daughter he never saw fatherless.

Visiting Ramseur’s deathbed during his final hours were some of his former West Point classmates, including George Custer, Wesley Merritt and Henry Dupont. Although enemies at Cedar Creek, these men had always remained friends. Ramseur is just one example of the over 8,600 casualties at Cedar Creek, all of them Americans.

Learn More: Battle of Cedar Creek