Marcie Schwartz

“I told [my sister] I had to go down town,” wrote Elisha Stockwell of Wisconsin, recalling his hasty enlistment at the age of 15 “She said, 'Hurry back, for dinner will soon be ready.' But I didn’t get back for two years.”

While the Civil War was called “The Boy’s War”, the enlistment of youths into the armed forces was not a new phenomenon in nineteenth century. Generations of boys had served in minor roles in armies and aboard vessels for centuries on both sides of the Atlantic. On this subject, President Abraham Lincoln sternly wrote to the Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, “The United States don’t need the service of boys who disobey their parents.” Despite the age restrictions and inexperience, a number of young boys did enlist on both sides to find adventure and “take the defiant South and set them straight” or, as one Southern boy pledged, to “die rather than become a slave to the North.”

Enlistment

When Elisha Stockwell signed his recruitment papers, he was not entirely honest: “I told the recruiting officer I didn’t know just how old I was but thought I was eighteen. He didn’t measure my height, but called me five feet five inches high. I wasn’t that tall two years later when I re-enlisted.” For most of the war, the minimum enlistment age in the North was legally held at 18 for soldiers and 16 for musicians, although younger men could enlist at the permission of their parents until 1862. In the South, the age limit for soldiers stayed at 18 until 1864 when it was legally dropped to 17.

There were many different ways that a young boy could get around the legal age limitations. Perhaps the easiest route was to lie about their age to the recruitment officers. Pressured by their superiors, officers often turned a blind eye to the evident youth of willing recruits in order to fill their recruitment quotas. Other recruitment officers who were ministers would use their congregations as recruitment pools. Parishioners were less hesitant to let their boys enlist because their regiment was led by good “Christian gentleman.”

Even schoolteachers used their influence with local recruitment officers to enlist their own students. “The schools in which I had been teaching had more than the usual number of large boys,” recalled Oscar L. Jackson of Hocking County, Ohio “They furnished quite a large squad of recruits of the very best material for good soldiers to start the proposed company.”

If the boy could not get around a stubborn recruitment officer, the line of inquiry then turned to the boy’s parents. When 16 year-old Ned Hutter of Mississippi went to join the Confederate Army, he was honest about his age. When ordered out of line, his father, who was right behind him, stepped in: “He can work as steady as any man, and he can shoot as straight as any who have been signed today.” The officer asked no further questions as he handed young Hutter a pen. Many fathers proved more than willing to help their underage sons sign up, especially when they would be accompanying them. Lt. Cornelius C. White of the Sixty Fourth Ohio was accompanied in December 1861 by his nine-year-old son, Albert, who served as a drummer for the regiment. After enduring the harsh winter and the carnage of the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, White sent his son home without procuring the proper discharge papers. The boy was listed as a deserter, but company officers looked the other way.

The last resort for boys unable to gain a parent’s consent was to simply run away from home and enlist in another town. Some boys enlisted under a false name so their parents (and the authorities) could not track them down. This method had an unforeseen consequence, though. The young men who died in battle or in hospitals were only known by their assumed names, leaving families without a clue as to their fate. Also, when applying for government pension benefits 30 years or so hence, some efforts ended in futility because the soldiers they served with could not recall who they were.

Roles

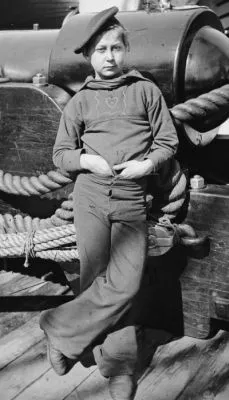

Once enlisted, the boys would perform a number of important functions within a regiment. Some were regular, enlisted soldiers, but others would become musicians, mounted couriers or runners, hospital attendants, guards, orderlies, chaplain assistants, water carriers, or barbers. At sea, they would serve as cabin boys, galley helpers, and powder boys.

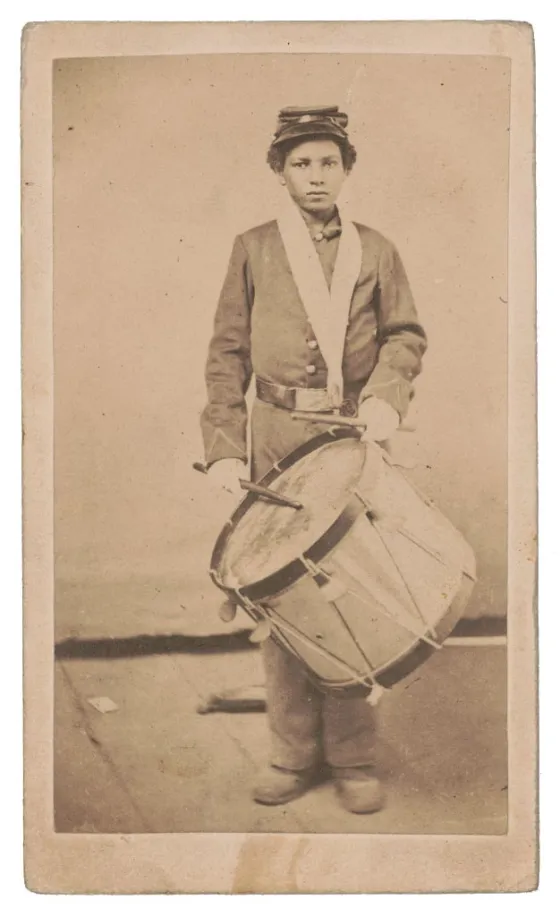

The musicians primarily played either the drums or the bugle. These boys marked the daily routine of the camp by signaling reveille, assembly, officer’s call, sick call, taps, and learned more than 40 distinctive calls to be used in battle. Their music also provided a source of entertainment for the troops as well as a festive flair for parades or regimental reviews. The most important job for these young musicians was to use their music to communicate orders during battle. The notes and beats of the instruments could carry commands quicker than a mounted courier, and father and more clearly than the human voice. Generally drummers were assigned to infantry regiments and buglers were assigned to cavalry or horse artillery as the bugle is more convenient to carry and play while mounted.

Powder boy, or powder monkey, like the position of a company drummer or bugler, was an old one in the Navy. Before the days of fixed ammunition, young boys brought up canvas bags or buckets of powder from the magazine to the gun carriage area, thus the name ‘powder monkey’. The powder monkeys, while technically required to follow the legal age regulations, were usually conscripted based on height and speed rather than age. A legal requirement of four feet, eight inches was placed upon the position as it was vital to be strong enough to perform their task, but also be short enough so they could be hidden behind the ships gunwale as they speedily ran back and forth between the cramped space beside their assigned gun and the magazine. While they were not an official member of the gun crew, they were essential during sea battles and were paid $10 a month plus regular seaman’s rations.

Camp Life

Once enlisted and given a position, there were still unique hurdles for the young boys to get over in camp life. Homesickness was a common problem for soldiers of any age but the boys “were so young they had little real sense of who they were or how they fit into the world. The one solid and reliable thing they knew—their families—had been left behind.”

An immediate material matter was finding a properly fitting uniform. The uniform sizes were standardized during the war and it was difficult to find the smaller sizes, let alone replace them. The officers would sometimes provide a favorite musician with an elaborate, but impractical parade outfit. Enlisted boys were paid and drew supplies like a regular soldier, but they could often not even find the basics such as socks or shoes that came in their size. Sixteen year old Abel Sheeks of Alabama had only the clothes he wore when he ran away from home, but their blue color, much too similar to the Union uniform, made them unsuitable for combat. He scavenged battlefields after each battle, looking for dead soldiers his approximate size. “I must confess to feeling very bad doing this … but I had no other course,” he recalled. “In just a few weeks, my uniform was the equal of anyone’s.”

On the parade ground, young drummers often found it difficult to maintain the regulation 28 inch pace during a march while carrying a standard issue drum. The tedium of drilling was also very hard on a young, restless mind. One young Union boy, quite fed up with the routine, snapped at his sergeant, “Let’s stop this fooling and go over to the grocery.” The drillmaster proceeded to order a corporal to take him out and “drill him like hell.” Afterward, the boy remarked, “It takes a raw recruit some time to learn that he is not to think or suggest, but obey.”

Bullying from the older soldiers also dampened a young recruit’s spirits. Stockwell encountered one soldier who “liked to try all recruits to see if they could fight.” “I didn’t enlist to fight that way,” Stockwell recalled telling the bully, “but if he would get his gun and go outside of the camp, we would stand thirty or forty rods apart, and I thought I could convince him that I could shoot as well as he could.”

These young recruits were also exposed to the previously forbidden adult vices of tobacco, alcohol, gambling and prostitution. Fourteen-year-old James Dickinson got in over his head while serving on board a gunboat on the Mississippi River. After indulging in some rum, he wrote: “[It] made me drunk. I puked on deck and could not stand up.” Dickinson was demoted as punishment.

In Battle

Boy soldiers faced life threatening challenges on the battlefield. Musicians were more often than not unarmed and this could prove fatal should they come into close quarters with the enemy. For many, the realization of what enlistment meant would truly hit home on the battlefield. “As we lay there and the shells were flying over us, my thoughts went back to my home” recalled Stockwell from his experience at the Battle of Shiloh “I thought what a foolish boy I was to run away to get into such a mess I was in. I would have been glad to have seen my father coming after me.”

While there were uniformed underage boys on both sides of the conflict, they rarely encountered each other except in heart wrenching cases like that of Union musician John A. Cockerill, age 16. “I passed the corpse of a beautiful boy in gray who lay with his blond curls scattered about his face,” he recalled as he walked the field after the Battle of Shiloh. “He was clad in a bright and neat uniform, well garnished with gold, which seemed to tell the story of a loving mother and sisters who had sent their household pet to the field of war…He was about my age…At the sight of the poor boy’s corpse, I burst into a regular boo hoo and started on.”

Even boys under the protection of senior officers, like Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's son, Fredrick Grant, were not immune to the trauma of warfare. “The horrors of the battlefield were brought vividly before me” he recalled from his time in Vicksburg. “I made my way with [a] detachment, which was gathering the wounded, to a log house which had been appropriated for a hospital. Here the scenes were so terrible that I became faint, and making my way to a tree, sat down, the most woebegone twelve year old in America.”