“Ruins opposite Circular Church” by photographer George N Barnard shows group of four African American boys in April 1865 sitting at base of pillar in Union occupied Charleston.

Marcie Schwartz

“In these few months” wrote twelve year old Celine Fremaux of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, “my childhood had slipped away from me. Necessity, human obligations, family pride and patriotism had taken entire possession of my little emaciated body.” Children on the Civil War home front encountered trials, hardships, and violence that forced them to grow up quickly amidst a nation at war with itself.

Responsibilities

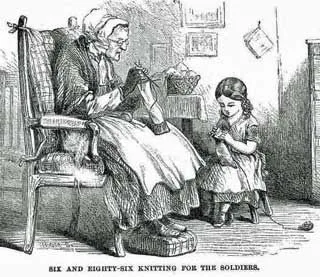

On the home front, both northern and southern children became critical to the war effort in a variety of ways. Children took up jobs that their fathers or brothers had left vacant or those that their mothers could not manage alone as the new head of the household. Children would help tend to livestock and crops, serve as clerks or helpers for the family business, cook meals, and watch their younger siblings while still trying to attend school. At school, children would build little Fort Sumters of mud and wooden blocks […] put up clothespins for soldiers, ruthlessly slaughtering them with shot from cannons made of old brass pistol barrels fastened to blocks of wood. Thirteen year old Dan Beard of Cincinnati, Ohio recalled making little Jefferson Davises "of potatoes and put sticks in them for legs. We hung the desperate potato men by their necks and shot them with squibs from firecrackers.” In the classroom, patriotism was also alive and well. John Bach McMaster of New York City remembered “every morning after Bible reading, the young woman who presided at the piano would sing a war song, the boys joining in, and that done, a second and perhaps a third would follow.” Many children, however, dropped out of school to support their families, and many others turned to homeschooling when their schools were closed for lack of funding or attendance, or when their schoolmaster went off to war.

“I was ten years old today. I did not have a cake;” mourned Carrie Berry of Atlanta “times are too hard. I hope that by my next birthday there will be peace in our land.” Shortages of these little luxuries, as well as household goods, were common, especially in the less industrialized South, and children were often tasked with making ends meet by sewing clothes and blankets, as well as making soap, candles, and gathering herbs for medicinal purposes. As the war progressed, many children scrabbled to have enough to eat, becoming active participants in the Southern Bread Riots that broke out in most of the major southern cities by 1863. Suffering from a lack of provisions, food and money, children formed looting bands to obtain goods for their families, as evidenced by the ultimatum scratched into a young Richmond girl’s journal: “We are starving. As soon as enough of us get together we are going to take the bakeries and each of us will take a loaf of bread. That is little enough for the government to give us after it has taken all our men.”

Entertainment

Despite these hardships, children managed to find ways to entertain themselves. “If it had not been for my books” wrote Emma LeConte of Columbia, South Carolina “it would indeed have been hard to bear. But in them I have lived and found my chief source of pleasure. I would take refuge in them from the sadness all around if it were not for other work to be done.” Reading, either from magazines, dime novels or books, was a primary pastime for children on both sides of the conflict.

In the North, magazines like Student and Schoolmate, The Little Pilgrim, and Our Young Folks were popular and contained numerous age appropriate articles, fictional stories, trivia, songs, games, patriotic plays to be put up, and poems related to the war. Oliver Optic’s produced entertaining wartime adventure tales such as The Young Lieutenant, Fighting Joe, Sailor Boy, and The Yankee Middy. While the magazine’s prose and Optic’s adventure stories focused on the drama and heroics of the war, they also promoted patriotism and virtue and the idea that the reader’s individual actions, no matter how small, contributed to something greater than themselves. Children were also able to obtain more factual accounts of the war like Following the Flag or Days and Nights on the Battlefield, battlefield maps, as well as more sensational dime novels.

In the South, paper, ink, and skilled printers were scarce, so new material was restricted mainly to hymns and bowdlerized textbooks designed to meet the same aims as their northern counterparts: make children aware of the issues that caused the war and to rally support for the Confederate war effort. The new textbooks spouted nationalism with names like The Dixie Primer, A New Southern Grammar, and The Confederate Spelling Book and their contents promoted values and issues pertinent to the southern cause. The 1863 Geographical Reader for the Dixie Children briefly explained the war from a southern perspective: “Thousands of lives have been lost, and the earth has been drenched with blood; but still Abraham is unable to conquer the “Rebels” as he calls the South. The South only asked to be let alone, and to divide the public property equally. It would have been wise of the North to have said to her Southern sisters, 'If you are not content to dwell with us any longer, depart in peace.'”

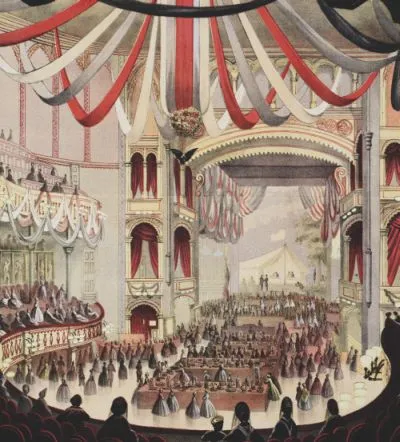

While books were the primary forms of entertainment at home, children could venture outside of the home for public shows and events, many of which revolved around the subject of the war. Children and their families often frequented plays, concerts, photography displays, magic lantern shows, martial parades, traveling panorama shows, and, in the North, Sanitary Fairs. The US Sanitary Commission allowed communities to directly support the war effort. Dan Beard recalled “every home and every school, parents, teachers and children were picking lint [for the Sanitary Commission] which was carefully placed on a clean piece of paper and used by the field surgeons to stanch the blood.” Held from late 1863 through 1865, Sanitary Fairs, sponsored by the Commission, raised more than four million dollars and provided some much needed levity and entertainment. After paying a small entrance fee, families could purchase donated goods, homemade pastries, locally grown crops, souvenirs, attend concerts and speeches, and gawk at war relics from the Revolution as well as captured Confederate armaments, trophies, and flags. Children would contribute their own handmade crafts to the fairs to be sold. “I made a model of a saddlebag loghouse which was very realistic,” wrote Dan Beard “I proudly carried that all the way to the Sanitary Fair. It was sold for seven dollars and a half, which was a severe blow to my artistic soul, because I really thought it was worth about fifty dollars.” Chicago closed its schools during the fairs of 1863 and 1865 so children could attend and support this patriotic event, and newspapers from the time depict children around the country running to see the Fair’s “treasury of useful articles, toys and knickknacks” as well as magic shows, ventriloquists, a “Gipsey tent,” and “a very remarkable animal called the Gorilla.”

The War Comes Home

The “home front”, however, especially in the South, was constantly under threat. Many of the battles were named after the towns that witnessed them, guerrilla raids harassed non-combatants, troops were garrisoned in houses and barns, and both armies left homes in ruins and fields littered with the dead and dying. In besieged cities, the situation for children and their families became desperate as the weeks turned into months of shelling. In Vicksburg, frightened citizens sought refuge in basements and even in caves. One young girl, Lucy McCrae, was almost hit by a shell and buried under flying rocks and dirt. “The blood was gushing from my nose, eyes, ears, and mouth,” she wrote “but no bones were broken.” On November 16, 1864, , ten year old Carrie Berry huddled with his family as occupied Atlanta burned around them: “They came burning the store house and about night it looked like the whole town was on fire. We all set up all night. If we had not sat up our house would have been burnt up for the fire was very near and the soldiers were going around setting houses on fire where they were not watched. They behaved very badly […] nobody knows what we have suffered since they came in.” Smaller southern cities and towns fared no better. In Winnsboro, North Carolina, a young girl witnessed “streets and vacant lots filled with homeless families […] when bringing bedding, raiment or provisions out of their burning homes, these were destroyed by the brutal soldiers. They stole much that was useless to them, for even Bibles were taken.” A seventeen year old widowed mother from Sandersville, Georgia lamented as soldiers “would walk up the steps of the back veranda on which we stood, and throwing down the hams and shoulders of our meat would cut them up in our very faces.” After the soldiers left with the rest of their belongings, she “knew that now our last hope for food was gone. I went to bed supperless […] sadder now was the thought, 'The cows are killed. I will be so hungry I cannot nurse Baby.'”

The northern home front also came face to face with the horrors of war, especially when armies collided in the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. On the first day of the fighting, fifteen year old Albertus McCreary watched from his porch as the street filled with “Union soldiers, running and pushing each other, sweaty and black from powder and dust. They called to us for water. While we were carrying water to the soldiers, a small drummer boy ran up the porch, and handing me his drum, said 'Keep this for me.' We were so busy that we did not notice how close the fighting was until, about a half a block away, we saw hand-to-hand conflict. An officer rode his horse up on the pavement and said 'All you good people go down in your cellars or you will all be killed.'” Even when the fighting ceased, townspeople were still left to pick up the pieces of their lives and care for the wounded thrust into their care.

Charles McCurdy, ten years old at the battle of Gettysburg, watched as the wounded in his barn “lay on the threshing floor […]they had received no care and were a pitiful and dreadful sight.” Fifteen year old Tillie Pierce’s house was repurposed as hospital for the wounded of Gettysburg and when she returned home she “fairly shrank back the awful sight presented. The approaches were crowded with wounded, dying and dead. By this time amputating benches had been placed about the house […]I saw the wounded throwing themselves wildly about, and shrieking with pain while the operation was going on. Just outside the yard I noticed a pile of limbs higher than the fence. It was a ghastly sight.” Albertus McCreary’s sister, seventeen year old Jennie, was tasked with rolling bandages. She and her next door neighbors “had not rolled many before we saw the street filled with wounded men. I never thought I could do anything about a wounded man but I find I had a little more nerve than I thought I had. [The first soldier] had walked from the field and was almost exhausted. He threw himself in the chair and said, 'O girls, I have as good a home as you. If I were only there!' He fainted directly afterward. That was the only time I cried.”

Contraband Camps

Perhaps the lives most put in jeopardy by the Civil War were those of former slaves and their children. As news of the Confiscation Act of 1861 and the employment of ‘contraband’ (escaped slaves) by the U.S. Navy and U.S Army spread, escaped slaves and their families began to congregate at places like Fort Monroe to appeal to become contraband. More than one hundred camps formed around Union held forts or encampments to house the escaped slaves. Despite being a welcome refuge for many, the camps often became overcrowded, and illnesses such as smallpox became endemic in the more makeshift sites. Children maintained an overwhelming numerical majority in the camp and, despite the varied conditions, all camps had a school. Most refugee children and many adults were able to spend at least some of their time in school, often managed by white northern missionaries. The rest of the hours were used to work in the fields to earn enough money to eat, and children as young as ten were send out to labor beside adults and typically given “one-quarter pay.” These camps were the center of the home front experience for escaped slaves, and presented a world of great contrast: they provided a glimpse of freedom, but poor living conditions and disease often ended the dream before it could truly begin.