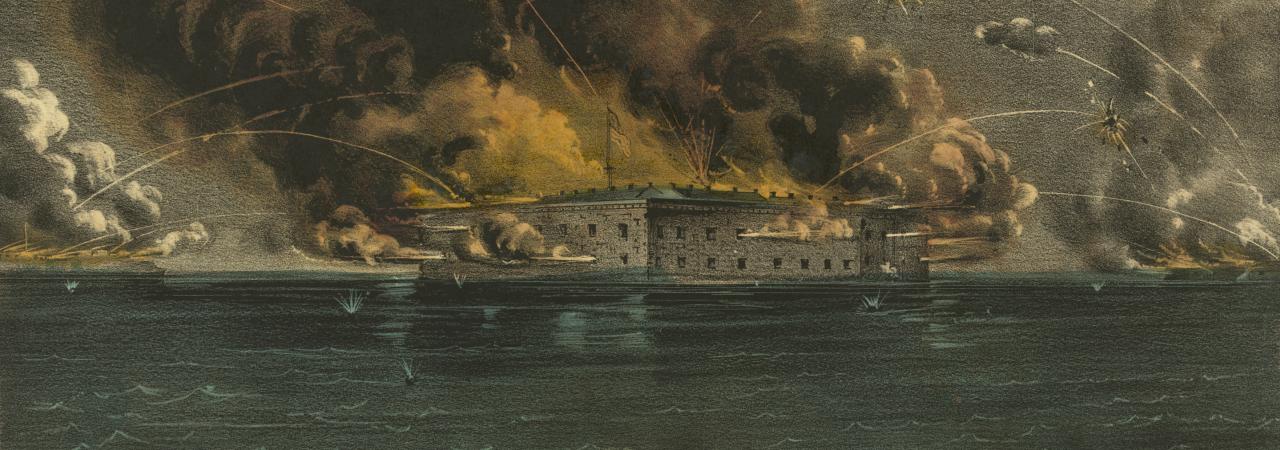

Bombardment of Fort Sumter, Charleston Harbor: 12th & 13th of April, 1861.

Fort Sumter

Charleston Harbor, SC | Apr 12 - 14, 1861

The attack on Fort Sumter marked the official beginning of the American Civil War—a war that lasted four years, cost the lives of more than 620,000 Americans, and freed 3.9 million enslaved people from bondage.

How it ended

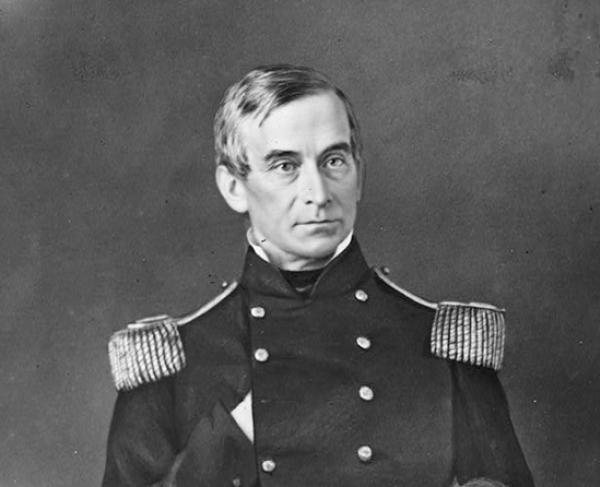

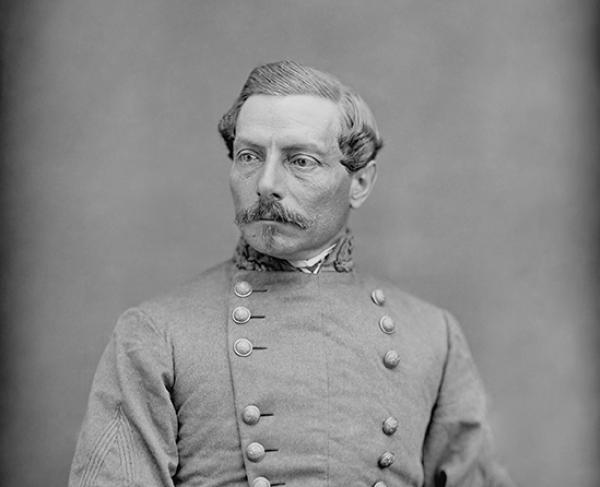

Confederate victory. With supplies nearly exhausted and his troops outnumbered, Union major Robert Anderson surrendered Fort Sumter to Brig. Gen. P.G.T Beauregard’s Confederate forces. Major Anderson and his men were allowed to strike their colors, fire a 100-gun salute, and board a ship bound for New York, where they were greeted as heroes. Both the North and South immediately called for volunteers to mobilize for war.

In context

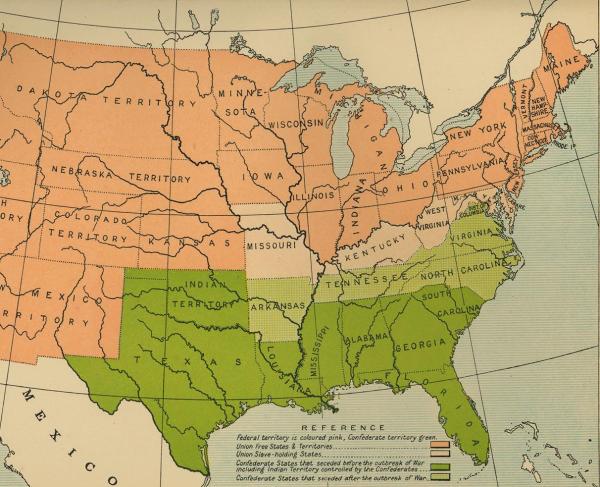

By 1861, the country had already experienced decades of short-lived but ultimately failed compromises concerning the expansion of slavery in the United States and its territories. The election of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States in 1860—a man who declared “I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free”—threatened the culture and economy of southern slave states and served as a catalyst for secession. On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the United States, and by February 2, 1861, six more states followed suit. Southern delegates met on February 4, 1861, in Montgomery, AL., and established the Confederate States of America, with Mississippi senator Jefferson Davis elected as its provisional president. Confederate militia forces began seizing United States forts and property throughout the south. With a lame-duck president in office, and a controversial president-elect poised to succeed him, the crisis approached a boiling point and exploded at Fort Sumter.

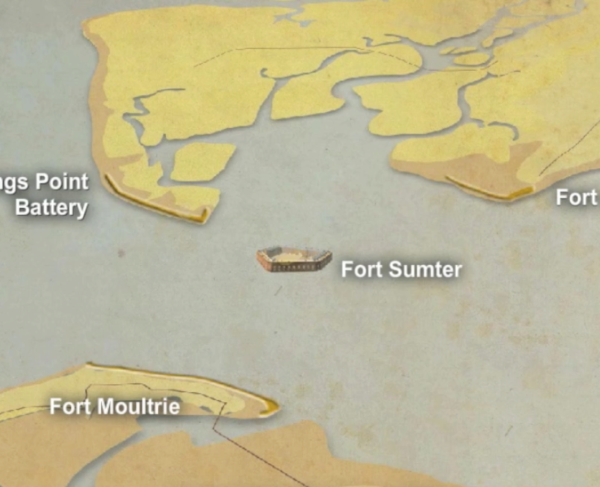

In Charleston, the birthplace of secession, tempers are on edge. A delegation from the state goes to Washington, D.C., demanding the surrender of the Federal military installations in the new “independent republic of South Carolina.” President James Buchanan refuses to comply. Charleston is the Confederacy’s most important port on the Southeast coast. The harbor is defended by three federal forts: Sumter; Castle Pinckney, one mile off the city’s Battery; and heavily armed Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island. Major Anderson’s command is based at Fort Moultrie, but with its guns pointed out to sea, it cannot defend a land attack. On December 26, Charlestonians awake to discover that Anderson and his tiny garrison of 90 men have slipped away from Fort Moultrie to the more defensible Fort Sumter. For secessionists, Anderson’s move is, as one Charlestonian wrote to a friend, “like casting a spark into a magazine,”

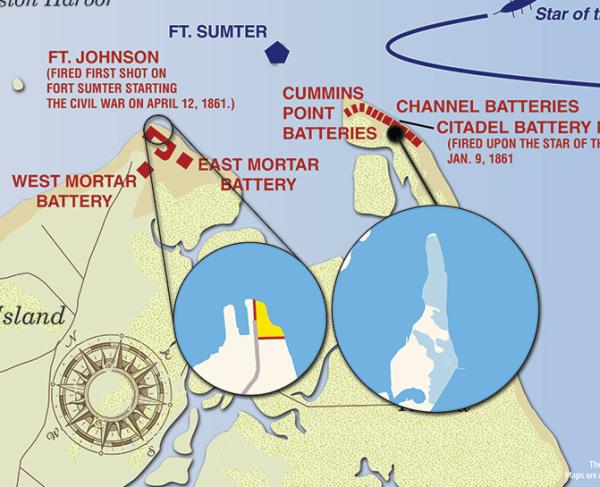

Adding to the major’s concern is his dangerously dwindling store of supplies. On January 5, 1861, the Star of the West departs from New York with some 200 reinforcements and provisions for the Sumter garrison. As the ship approaches Charleston Harbor on January 9, cadets from the Citadel fire, forcing the crew to abandon its mission. On March 1, Jefferson Davis orders Brig. Gen P.G.T. Beauregard to take command of the growing southern forces in Charleston. On April 4, Lincoln informs southern delegates that he intends to attempt to resupply Fort Sumter, as its garrison is now critically in need. To South Carolinians, any attempt to reinforce Sumter means war. “Now the issue of battle is to be forced upon us,” declared the Charleston Mercury. “We will meet the invader, and the God of Battles must decide the issue between the hostile hirelings of Abolition hate and Northern tyranny.”

On April 9, Davis and the Confederate cabinet decide to “strike a blow!” Davis orders Beauregard to take Fort Sumter. The next day, three of Beauregard’s aides sail to the fort and courteously demand the garrison’s surrender. Anderson is equally courteous, but refuses: “I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication demanding the evacuation of this fort, and to say, in reply thereto, that it is a demand with which I regret that my sense of honor, and of my obligations to my Government, prevent my compliance.” He also informs the delegation that the garrison’s supplies will only last until April 15.

April 12. At 4:30 a.m., a flaming mortar shot arcs into the air and explodes over Fort Sumter. On this signal, Confederate guns from fortifications and floating batteries around Charleston Harbor roar to life. Outmanned, outgunned, undersupplied, and nearly surrounded by enemy batteries, Anderson waits until around 7:00 a.m. to respond. Captain Abner Doubleday volunteers to fire the first cannon at the Confederates, a 32-pound shot that bounces off the roof of the Iron Battery on Cummings Point.

For nearly 36 hours the two sides keep up this unequal contest. A shell strikes the flagpole of Fort Sumter, and the American colors fall to the earth, only to be hoisted back up the hastily repaired pole. Confederates fire hotshot from Fort Moultrie into Fort Sumter. Buildings begin to burn within the fort. With no more resources, Anderson surrenders Fort Sumter to Confederate forces.

April 13. At 2:30 p.m., Maj. Anderson and his men strike their colors and prepare to leave the fort. Sadly, the only casualties at Fort Sumter come during the 100-gun salute, when a round explodes prematurely, killing Pvt. Daniel Hough and mortally wounding another soldier. The attack is over, but the war had just begun.

0

0

Following the evacuation of Major Robert Anderson and his Federal garrison on the afternoon of April 14, 1861, Fort Sumter is occupied initially by Confederate troops of Company B of the First South Carolina Artillery Battalion and a volunteer company of the Palmetto Guard, a local militia unit. The fort remains in Confederate hands for the next four years until all Confederate forces evacuate Charleston on the evening of February 17, 1865.

Despite having surrendered, Anderson and his men are greeted as heroes when they disembark in New York. Capt. Abner Doubleday notes later that “all the passing steamers saluted us with their steam-whistles and bells, and cheer after cheer went up from the ferry boats and vessels in the harbor.” Anderson’s valor during the attack and commitment to duty are praised by the Union. Beauregard is also hailed for this first Confederate victory. He is later ordered to direct the troops at Bull Run.

After Lincoln’s election and the secession of the southern states, small numbers of enslaved people began showing up at Union forts in the hopes of taking refuge. But Union commanders were not charged with protecting slaves and promptly returned them to their masters. One such slave—a teenager—made his way across Charleston Harbor to Fort Sumter in March of 1861 to appeal to Major Anderson, but was turned over to marshals in Charleston.

With Union troops in their midst, white residents of Charleston were increasingly concerned about runaway slaves. Of even greater worry, however, was the possibility of a slave uprising. Mary Chestnut, wife of prominent Charleston politician and Confederate colonel James Chestnut, started keeping a diary in February 1861. As events unfolded across Charleston Harbor on April 12, she wondered how the action at Fort Sumter would impact the future.

Not by one word or look can we detect any change in the demeanor of these negro servants. Lawrence sits at our door, sleepy and respectful, and profoundly indifferent. So are they all, but they carry it too far. You could not tell that they even heard the awful roar going on in the bay, though it has been dinning in their ears night and day. People talk before them as if they were chairs and tables. They make no sign. Are they stolidly stupid? or wiser than we are; silent and strong, biding their time?

With the start of the Civil War, desperate refugees from slavery began to flood Union camps in earnest, but the government in Washington still had no consistent policy regarding fugitives. Often their fate was in the hands of the individual commanders. Finally, on August 6, 1861, the North declared fugitive slaves to be "contraband of war" if their labor had been used to aid the Confederacy. Contrabands were considered free and were protected by the Union army.

As the reality of war sunk in, slaveholders in the South hoped that their slaves would remain loyal to them. Some did, and the slave uprising that Mary Chestnut feared never came. But the exodus of enslaved people who crossed Union lines and made their way to freedom steadily increased after guns were fired at Fort Sumter. By 1863, approximately 10,000 former slaves flooded Washington. By the end of the Civil War, as many as 40,000 fugitives had made their way to the Union capital.

Both Beauregard and Anderson attended the United States Military Academy at West Point. In fact, Anderson had been Beauregard’s artillery instructor there, and later Beauregard served at the school’s superintendent. The Academy was—and is—the premier school for American soldiers. Before the Civil War, the institution trained both northerners and southerners to be the elite fighting force of the nation.

When the nation divided over slavery and secession loomed, the bonds that linked the close-knit classes at West Point began to fray. Some southern cadets felt duty-bound to depart for the Confederate States of America, which was seeking officers for its newly formed military. Many of the cadets from the north, who had been indifferent to southern politics and secession, suddenly rallied to defend the Union after the attack on Fort Sumter.

Beauregard, a native of Louisiana, declared his secessionist leanings while still superintendent at West Point and quickly left to sign up with the Confederate army. Anderson, though a native of Kentucky and former slave owner, remained faithful to the Union and was assigned to command its forces in Charleston. These West Point soldiers knew how to command. Their communications before and during the battle reflect the courtesy and professionalism of career officers.

Regardless of any personal feelings he may have felt toward Anderson, Beauregard had his orders. He instructed his aide-de-camp to send the major this formal heads-up on April 12 at 3:30 a.m.:

SIR: By authority of Brigadier-General Beauregard, commanding the Provisional Forces of the Confederate States, we have the honor to notify you that he will open the fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hour from this time.

Fort Sumter: Featured Resources

Related Battles

80

500