December 20, 1860: the fateful date on which Southern secession from the American republic left the realm of rhetoric and philosophy and entered the uncomfortable dominion of reality. Or, so the story is often written. However, the truth is that the fate of the entire South was not yet fully cast in December 1860 when South Carolina declared her independence; the rest of the Southern states still wrestled with the future of their place in a Southern confederacy.

A tumultuous, riotous, raucous and eventful “secession winter” awaited, and the people of the South spoke with anything but one voice. Instead, the diverse and wide-ranging voices of secession present us with a complex and intriguing picture of the South on the eve of Civil War.

On the extreme end of that perspective were the rabid and radical so-called fire-eaters, who demanded the immediate secession of all slaveholding states from the Union. Among this brand of radicals were many prolific writers, yet Edmund Ruffin left what some consider the “best” extremist viewpoint from this tumultuous era. Born in the last decade of the 18th century in Virginia, Ruffin was an early and ardent supporter of secession, making emboldened pleas to defend Southern rights and the institution of slavery by “the strong hand against the Northern abolitionists” as early as 1845.

Ruffin’s passion for secession and hatred of what he called the “Yankee race” was only emboldened by John Brown’s now infamous raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859. Following the raid and the subsequent hanging of Brown for treason, Ruffin—never missing an opportunity to publicize secession—sent several of Brown’s notorious pikes throughout the South with a label attached that read: “Sample of the favors designed for us by our Northern brethren.”

After years of tireless work advocating the secession of the Southern states, and after the experience of Brown’s raid, Ruffin was incredulous that his native Virginia did not immediately secede following the election of President Abraham Lincoln, stating that,

If Virginia remains in the Union under the domination of this infamous, low, vulgar tyranny of Black Republicanism, and there is one other state in the Union that has bravely thrown off the yoke, I will seek my domicile in that state and abandon Virginia forever.

Ultimately, Ruffin did leave his native state for South Carolina and was present to witness that state’s vote to secede from the Union on December 20, 1860.

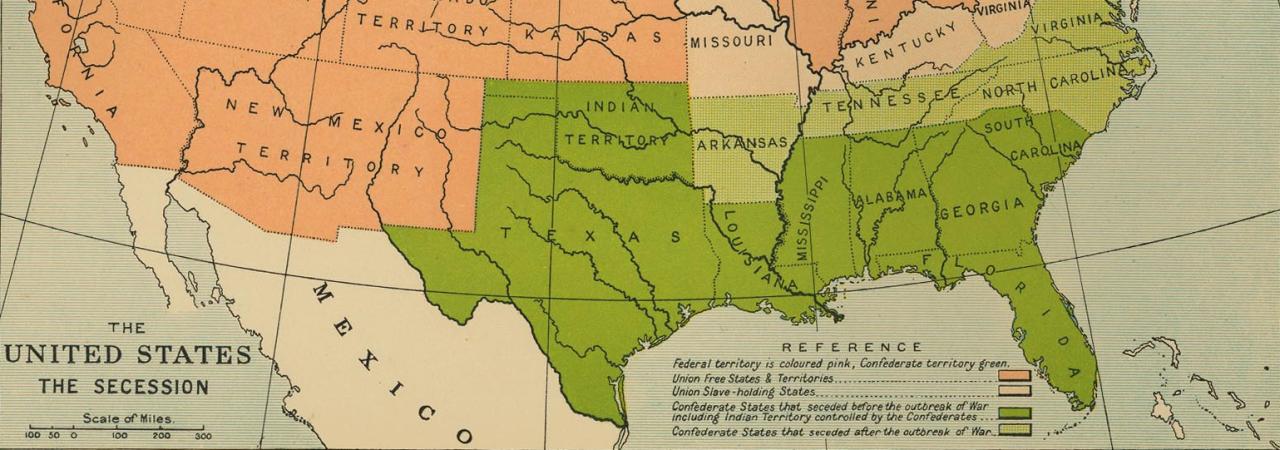

In the weeks and months to come, the majority of the Deep South followed the example of Ruffin and the state of South Carolina by casting their fate with the fledgling Confederacy. Yet their respective decisions to secede in the first few months of 1861 only made the plight of the Upper South (Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia) and the slaveholding border states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Missouri) even more difficult.

Mrs. Mary Boykin Chesnut, the prolific diarist of Charleston, S. C., chronicled the events that followed the secession of the Palmetto State. Chesnut wrote that during January 1861 the talk around the table could be condensed to a call for the Upper South to join the Deep South, or as she put it, “Now for Virginia!...Those who want a row are in high glee. Those who dread it are glum and thoughtful enough.”

In reality though, the opinions of fire-eaters like Edmund Ruffin no more represented the feelings of most moderate Southerners, especially citizens of the Upper South, than a rabid abolitionist would have accurately represented the majority of Northerners on the eve of the conflict. While South Carolina’s secession drew the other cotton states of the Deep South into a southern confederacy, the decision was not as simple for much of the Upper South, which had developed strong economic ties with its northern brethren.

In Virginia, which straddled that economic divide, the prevailing sentiment held that some type of brokered compromise could quell the late unpleasantness — that, in fact, the Union should prevail. The future famed leader of the Army of Northern Virginia himself, Robert E. Lee, expressed this feeling in the strongest terms in a letter he wrote in January 1861,

I can anticipate no greater calamity for the country than a dissolution of the Union. It would be an accumulation of all the evils we complain of, and I am willing to sacrifice everything but honor for its preservation. I hope, therefore, that all constitutional means will be exhausted before there is a resort to force. Secession is nothing but revolution.

Lee closed the letter with a portentous clarification, noting that, “If the Union is dissolved, and the Government disrupted, I shall return to my native State and share the miseries of my people, and save in defense will draw my sword on none.”

No less than Lee’s future lieutenant, Thomas Jonathan Jackson, (who would later gain the moniker “Stonewall”) elucidated a similar moderate view of current events in a letter penned in February 1861. While the Old Dominion prepared to send delegates to a peace conference in Washington, D.C., Jackson wrote,

I am much gratified to see a strong Union feeling in my portion of the state ... For my own part I intend to vote for the Union candidate for the convention and I desire to see every honorable means used for peace, and I believe that Providence will bless such means with the fruits of peace.

If Jackson’s calm hope for a peaceful mediation represented the moderate viewpoint, those Virginians living in the far western counties of the Commonwealth spoke for Southerners who believed in the preservation of the Union at all costs. In what would eventually become the breakaway bastion of Unionism known since as West Virginia, a pro-Union group in Tyler County explained its position and warned, “[If Virginia secedes from the Union] we are in favor of striking West Virginia from Eastern Virginia and forming a state independent of the south, and firm to the Union.”

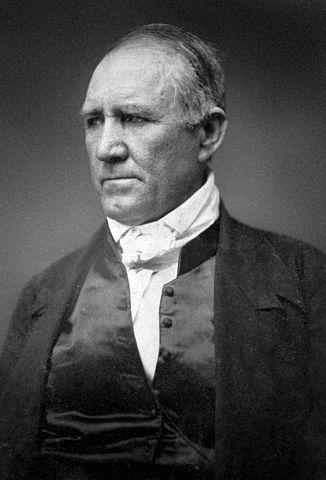

This rabid pro-Unionism was not unique to the western counties of the Virginia, as large portions of the rugged Appalachian hill country of eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina and northern Georgia were populated by fiercely independent and often pro-Union citizens. Beyond these geographic pockets of Union loyalty there also were outspoken Southern critics of the movement toward secession and war. No less than the irascible Sam Houston, then governor of Texas, could be counted among that group of strident Unionists. As Texas made the fateful decision to secede in February, Governor Houston ominously predicted,

To secede from the Union and set up another government would cause war. If you go to war with the United States, you will never conquer her, as she has the money and the men. If she does not whip you by guns, powder, and steel, she will starve you to death. It will take the flower of the country—the young men.

As the Upper South confronted the cruel reality of secession in the winter of 1861, the slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri wrestled with the same dilemma. As was certainly the case in Virginia and her sister states of the Upper South, there was no singular voice or approach to the issue, and divided loyalties were commonplace across the border between North and South.

In Maryland, the dividing line surveyed by Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon in the 18th century, still cut a swath between slave state and free in 1860. To the north, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the peculiar institution had been outlawed, while neighboring Marylanders still retained the right to own human chattel. Thus, as the fall of 1860 faded into winter, Maryland wrestled with its identity. The Old Line State saw loyalties split largely along an east-west axis, with the rugged terrain of western Maryland predominantly loyal to the Union. Ultimately, Maryland was not quite northern, and not exactly southern, and as a result, straddled a dangerous divide in the weeks leading up to and following the secession of the Deep South.

Thomas Holliday Hicks, then governor of Maryland, may himself best personify the perplexing position of Maryland in late 1860 and early 1861. A native of Maryland’s eastern shore, Hicks was elected governor in 1857 as a member of the ultra-nativist “Know-Nothing” Party. Known for speaking of the South as “we,” in reference to his understanding of Maryland’s loyalty, he would ultimately hold on to power throughout the secession crisis. In doing so he held Maryland—through force and coercion—in the Union. However, prior to the secession of South Carolina, it was Hicks who noted to a member of the House of Delegates that,

...the rights of the south, guaranteed by the constitution, should be respected and enforced. If they are not, then in my judgment we shall be fully warranted in demanding a division of the country.

Yet, following the fateful decision of South Carolina to ‘demand a division,’ Hicks grappled with secession, asking, “Should I be compelled to witness the downfall of that Government inherited from our fathers, established, as it were, by the special favor of God?”

Like his native state, and many other border states, Hicks found that an answer to that question would not come easily. From Delaware to Missouri, pro-Union and pro-secession factions battled, in some cases openly, for control of their respective states. Though Delaware remained firmly in the Union, and Maryland remained only after the considerable exertion of force, keeping Kentucky and Missouri within the Union proved exceedingly difficult.

In Kentucky, many voices, including that of Gov. Beriah Magoffin openly called for neutrality— a position that pleased neither the Confederate nor Union governments. In Missouri, a state which also advocated a position of neutrality, only a force of arms truly kept the state from slipping into Confederate control, despite several futile attempts to declare the state “seceded” from the Union. Ultimately, through force, coercion and cunning political skill the Lincoln administration held tight to its border states and their key strategic value as war slowly approached.

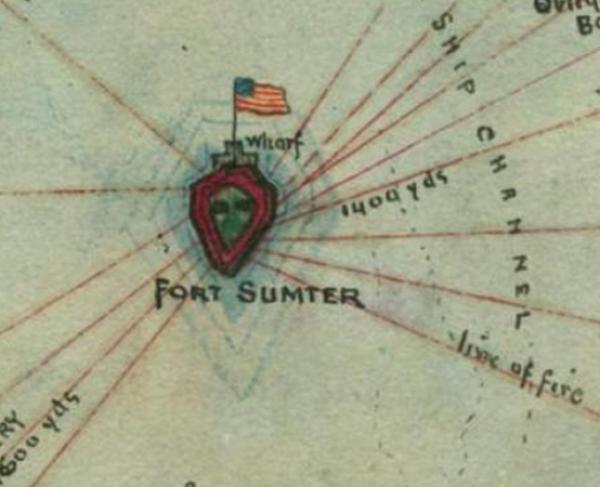

Despite these efforts—and the calls for moderation throughout much of the Upper South—the high hopes for a brokered compromise vanished when, on April 12, 1861, at 4:30 a.m., Confederate batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, S.C. On April 15, in the wake of the fort’s surrender, President Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 75,000 troops “in order to suppress said combinations, and to cause the laws to be duly executed” and “to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular government; and to redress wrongs already long enough endured.”

In issuing this call, President Lincoln left the Upper South with few choices. Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia would not be compelled to take up arms against their sister states of the South. On April 17, Virginia, the mother state of the Union, cast her fate with the Confederacy by passing an ordinance of secession. Following that vote, Virginia’s governor John Letcher dispatched a telegram to U.S. Secretary of War, Simon Cameron. In it he noted, “You have chosen to inaugurate civil war, and, having done so, we will meet it in a spirit as determined as the administration has exhibited toward the South.”

In the following months, Virginia would be joined by the rest of the Upper South, and the war would begin in earnest. The determined spirit of the South was a force to be reckoned with for the next four years of harrowing combat across the continent. From Manassas to Chickamauga to Appomattox, the South boldly defended the right of secession. Yet the same division that existed in 1860 over the basic principal of secession would never entirely heal—leaving the new nation to fight a war on two fronts: one against its Yankee foes and one to keep the home front united. That two-front war may have begun on December 20, 1860, but it would take four more years, and the lives of 620,000 Americans to finally settle.