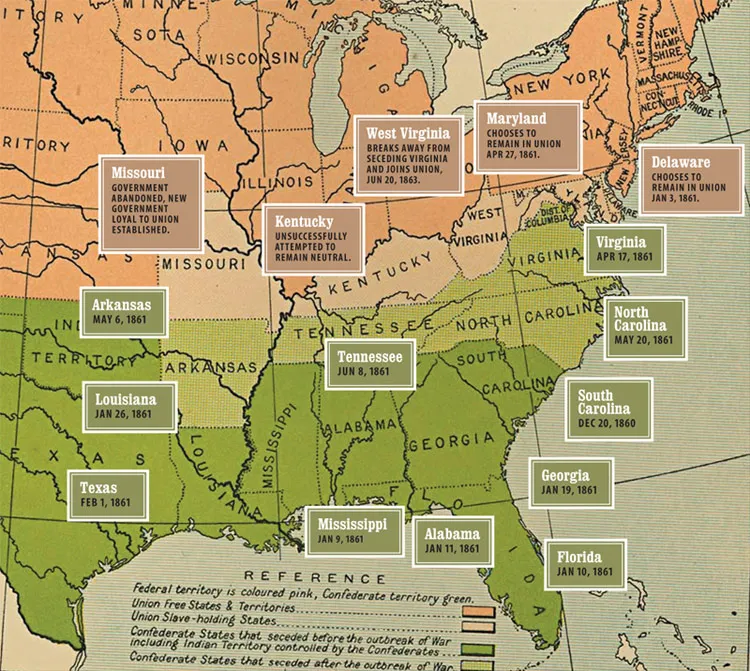

After the seven states of the Deep South formed the Confederate States of American in February 1861, the eight remaining slaveholding states faced a choice—either contribute to the escalating crisis through secession or remain in the Union despite the perceived Federal coercion. But when shots were fired at their Southern brethren and Washington called for 75,000 volunteers to quell the insurrection, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas cast their lot with the Confederacy. Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland and Delaware, “border” states all, were left to determine where their loyalties lay.

Delaware, with few slaves and extensive economic ties to the North, voted overwhelmingly to remain in the Union and the question was closed. While there was popular support for secession in Maryland, on April 27, the state legislature determined that although it did not have the authority to declare secession it would reserve the state’s right to do so. Given the state’s strategic importance for the defense of Washington and the passage of Union troops, Lincoln preempted any such decision by declaring martial law, suspending habeas corpus and arresting pro-Southern politicians.

Missouri tried to remain nonaligned, with the General Assembly acting to create the State Guard to defend the state’s neutrality after Union troops fired on rioting crowds in St. Louis. Lincoln rejected such compromise and dispatched Capt. Nathaniel Lyon to enforce federal demands that Missouri raise troops for the Union. Pro-Southern governor Claiborne Jackson fled, and his government-in-exile was recognized by the Confederacy. In July, however, a constitutional convention declared the government vacant and appointed a pro-Union governor.

While both sides initially respected Kentucky’s efforts to remain neutral, it didn’t stop them from positioning troops along her borders in anticipation. Many volunteers slipped away to join the respective armies, while dueling militias developed within the state. Summer elections resulted in a pro-Union legislature and the resignation of the pro-South governor. The tenuous truce became untenable when Southern forces occupied highlands over the Mississippi River, prompting Union general Ulysses S. Grant to take control of the mouth of the Tennessee River. The solidly pro-Union government demanded the withdrawal of Confederate forces, precipitating the development of a pro-Southern convention that voted for secession and formed another government-in-exile.