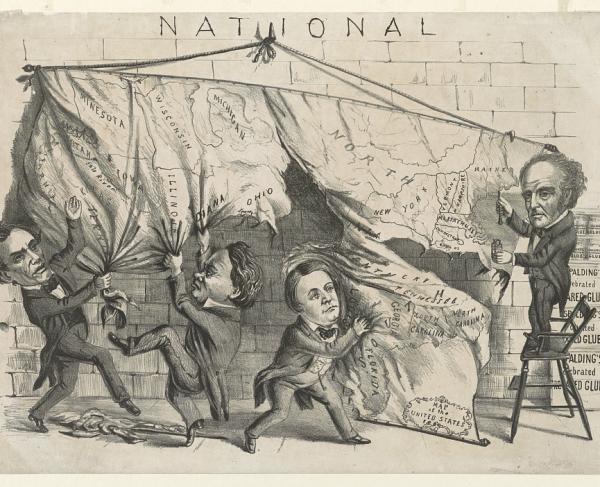

As the Civil War drew to a close in 1865, Southerners looked around at the death and destruction that the war had inflicted on their homes, businesses, towns, and families. “The South was not only…conquered, it was utterly destroyed…More than half [of] the farm machinery was ruined, and…Southern wealth decreased by 60 percent,” states historian James M. McPherson. With the abolition of slavery becoming the law of the land in 1865, it became harder and harder for many Southerners to justify the purpose of secession and the war as they grieved over the deaths of nearly 300,000 of their sons, brothers, fathers, and husbands. Thus, many Southerners set to work to remember the Confederate cause in a positive light. Former Confederate general and one-time commander of the United Confederate Veterans claimed, “If we cannot justify the South in the act of Secession, we will go down in History [sic] solely as a brave, impulsive but rash people who attempted in an illegal manner to overthrow the Union for our Country.” Thus, from the ashes of war, the “Lost Cause” was born.

There are six main parts of the Lost Cause myth, the first and most important of which is that secession had little or nothing to do with the institution of slavery. Southern states seceded to protect their rights, their homes, and to throw off the shackles of a tyrannical government. To the proponents of the Lost Cause, secession was constitutional, and the Confederacy was the natural heir to the American Revolution. Because secession was constitutional, those who fought for the Confederacy were not traitors. Northerners, specifically Northern abolitionists, caused the war with their fiery rhetoric and agitating, even though slavery was on its way to gradually dying a natural death. They also argued secession was a way to preserve the Southern agrarian way of life in the face of encroaching Northern industrialism.

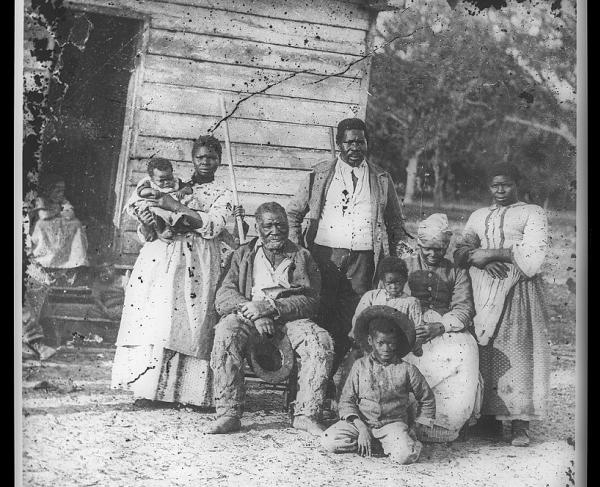

Second, slavery was portrayed as a positive good; submissive, happy, and faithful slaves were better off in the system of chattel slavery which offered them protection. Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens declared in 1861 “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” After the war, these formerly enslaved people were now said to be unprepared for freedom, which was an argument against Reconstruction and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments of the Constitution.

The third tenet states that the Confederacy was only defeated because of the Northern states’ numerical advantage in both men and resources. The Confederate Army was less defeated than overwhelmed, as their lesser resources. Former Confederate officer Jubal A. Early justified the Southern defeat by stating that the North “finally outproduced that exhaustion of our army and resources, and that accumulation of numbers on the other side which wrought our final disaster.” Early went on to say that the South “had been gradually worn down by combined agencies of numbers, steam-power, railroads, mechanism, and all the resources of physical science.” The lack of southern manufacturing and the outnumbered population doomed it to failure from the start. Thus, the “Lost Cause.”

Fourth, Confederate soldiers are portrayed as heroic, gallant, and saintly. Even after the surrender, they retained their honor. At one reunion oration, Confederate General Thomas R. R. Cobb, who was killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg, was compared to “Joshua in his courage,…St. Paul in the logic of his eloquence and [St.] Stephen in the triumph of his martyrdom.”

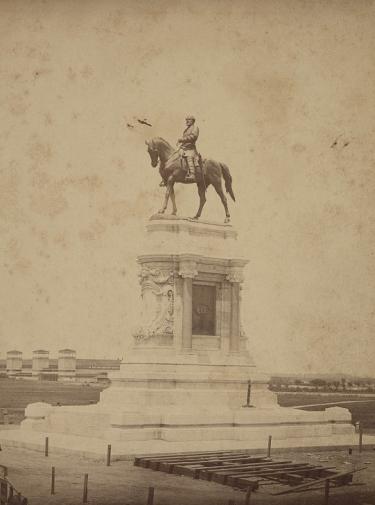

Fifth, Robert E. Lee emerged as the most sanctified figure in Lost Cause lore, especially after his death in 1870. Lee himself became a symbol for the Lost Cause, and a “Cult of Lee” revered the Virginian as the ultimate Christian soldier who took up arms for his state. He was even called the second Washington. Lee was the most successful of all Confederate Army commanders, and after the war, Jubal Early and many former Southern officers placed Lee upon a pedestal. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson became a martyr, wounded by his men while defending the Lost Cause. Even the office building where Jackson died bore the name “The Stonewall Jackson Shrine” for decades. On the other hand, James Longstreet became a villain to Lee and Jackson’s heroes, blamed for the loss at Gettysburg and vilified for his newfound Republican affiliation and the temerity to question Lee’s wartime decisions. Even former Confederate President Jefferson Davis became a reverential figure, seen as the personification of states’ rights.

Finally, Southern women also steadfastly supported the cause, sacrificing their men, time, and resources more than their Northern counterparts. The idealized image of a pure, saintly, white Southern woman emerged as well.

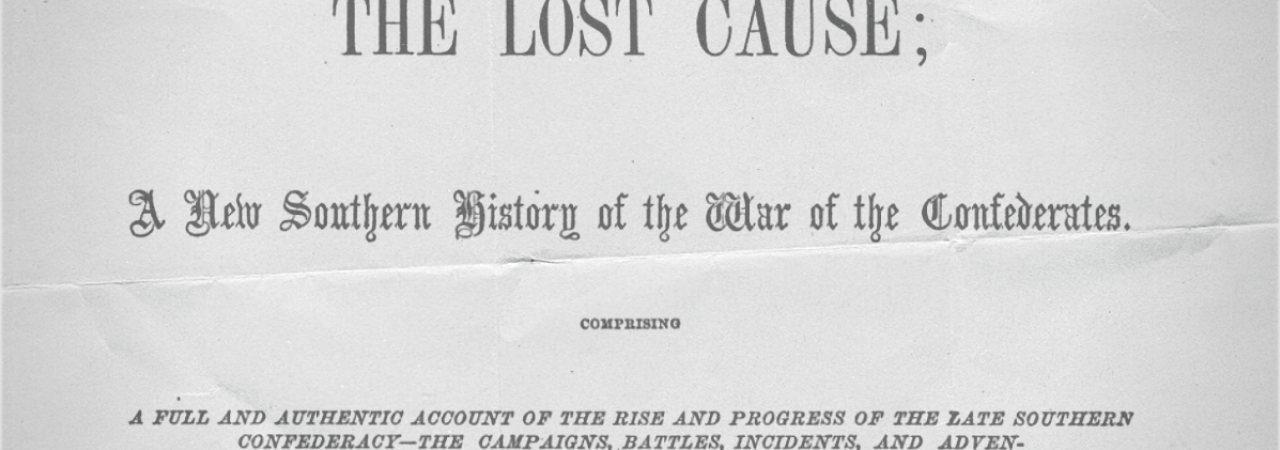

Many of the motifs of the Lost Cause emerged before the war was officially over. In Lee’s farewell address to the Army of Northern Virginia the day after he surrendered at Appomattox Court House, he thanks his soldiers for “four years of unsurpassed courage and fortitude.” But in the face of “overwhelming numbers and resources,” he was forced to surrender the army to prevent further bloodshed. But the term “Lost Cause” originated almost immediately after the war ended. Edward Pollard, the editor of the Richmond Examiner, published The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates, his own justification for the war effort. In 1867, Pollard’s brother H. Rives published one of the first Lost Cause periodicals called the Southern Opinion. This weekly paper argued for a distinctive Southern culture and for the preservation of the heroism of their cause.

Southern women played a large role in perpetuating the Lost Cause. They converted their wartime soldiers’ aid organizations into memorial organizations, to commemorate their male counterparts who fell during the war. Because women were seen as inherently nonpolitical, and memorializing was not seen as political, they were able to take the lead in memorializing the Southern cause. Ladies’ Memorial Associations were formed all across the South to dedicate Confederate cemeteries and organized Memorial Days for fallen Confederates. They would eventually unite in 1900 to become the Confederated Southern Memorial Association, and by then, their goals had expanded beyond just remembering their dead. Now, they collected Confederate relics and instilled veneration for the Southern cause in the younger generation through textbooks and educational outreach efforts.

In 1869, Confederate veterans including Braxton Bragg, Fitzhugh Lee, and Jubal Early created the Southern Historical Society and the Lost Cause was central to its mission. In 1876, the society published the Southern Historical Society Papers, a collection of essays defending every aspect of the Southern war effort. Early became the most influential figure in propagating these arguments. While initially against secession, Early steadily rose through the ranks of the Confederate Army. After the war, he traveled the South, giving lectures and writing articles to defend Lee and attack Longstreet. He also espoused the notion that the war in Virginia was the central theater of the war. Jefferson Davis also published The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, a vindication of the war.

By the 1880s, many Confederate veteran associations formed to both perpetuate the memory of their fallen brothers and take care of the disabled. These groups consolidated into the United Confederate Veterans in 1889. Auxiliary organizations such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy formed for similar purposes. The Confederate Veteran was founded in 1893 and became the official mouthpiece of the Lost Cause movement. This publication reached a mass audience until it was discontinued in 1932.

Some in the North, especially Union veterans and African Americans, were angered by glorifying the Confederate cause and slavery. However, general public opinion had shifted towards reconciliation with the defeated South, especially after they became disillusioned with Reconstruction. It was telling when two ex-Confederates were pallbearers at Ulysses S. Grant’s funeral. Thus, many Northerners accepted the Lost Cause narrative as a way to mend the wounds of the war and to move the country forward into the twentieth century.

Further Reading:

- Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory By: David W. Blight

- The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History By: Gary Gallagher and Alan T. Nolan

- Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation By: Caroline E. Janney

- Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920 By: Charles R. Wilson