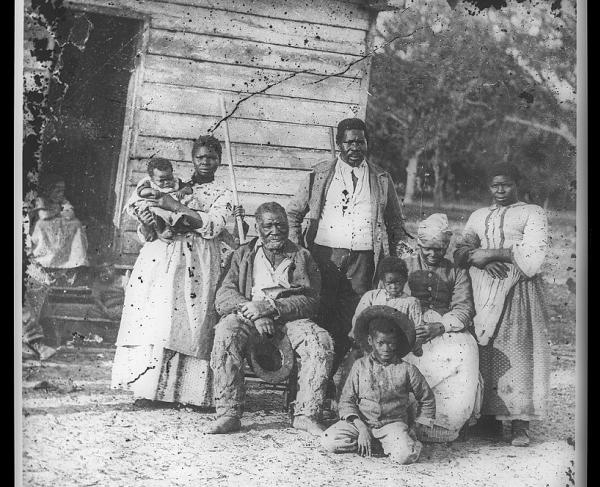

Picking cotton in Savannah, Georgia.

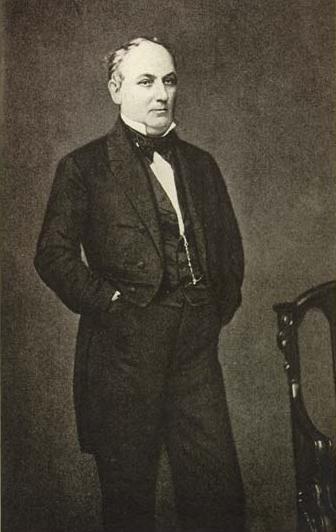

James Hammond, a southern plantation owner, and U.S. Senator extolled Southern power. In his speech to the United States Senate on March 4, 1858, he put words to a long-brewing Southern philosophy: “Cotton is King.”

“Without firing a gun, without drawing a sword, should they make war on us we could bring the whole world to our feet […] What would happen if no cotton was furnished for three years? I will not stop to depict what everyone can imagine, but this is certain: England would topple headlong and carry the whole civilized world with her, save the South. No, you dare not make war on cotton. No power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is king.”

This philosophy emerged from economic debates in the 1850s. In the 1850 census, the South contained only 18% of the United States' manufacturing capacity. Routinely, the South would sell 70% of their raw cotton to the North and buy the North’s manufactured cotton goods at a higher capital. In the early 1850s, many people below the Mason Dixon Line wanted to “throw off the degrading shackles of our commercial dependence” and increase the manufacturing ability of the South. Within the decade, rail lines were established between major southern cities to increase the movement of goods. In addition, more textile factories were established in the southern states and iron foundries, like Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, demonstrated that industry could be conducted on a large scale in the region. However, Lowell, Massachusetts, operated more textile manufacturers than the entirety of the South in 1860 and industry in the South didn’t eclipse the growth of the industry in the north during the 1850s.

While there was a push for more industrialization, many gentlemen farmers of the Southern states opposed the idea of increased southern industrialization. The South’s economy was built on agricultural production of cash-crops, which were cotton, rice, indigo, and tobacco. The bulk of profit earned from these harvests was directed toward maintaining their social standing, and the acquisition of more slaves in order to work the land and produce more crops.

Between the North and South, economists debating the economic superiority between “free” labor and “enslaved” labor. Supporters of “enslaved labor” likened enslavement to socialism. Slaves, many argued, were fed, clothed, and sheltered for life regardless of the amount of work they do. Children, who were too young to work, and the elderly, who were too old to work, were still “taken care of” on the plantation. In contrast, individuals who can not work in the Northern capitalistic “free” society would have to rely on friends, families, and private enterprise to ensure they were not hungry or homeless when unemployed. Supporters of “free” labor noted that individuals with “free enterprise” would be more industrious because they desired to better themselves and gain more capital and argued that “enslaved” labor would not feel this same drive and, consequently, try to work as little as possible—a form of passive slave resistance.

Amongst these debates, the “Cotton is King,” of “King Cotton,” concept perforated into the Southern consciousness. Elites believed that the North would bow to Southern demands because of their reliance on Southern products in their manufacturing industry. This concept wasn’t constrained by national borders, the South believed that they could gain international recognition because foreign markets, specifically European markets, relied on their Southern goods.

After the South declared secession from the United States of America and created the Confederate States of America, they sought international recognition of statehood in Europe. In February 1861, a commission headed by William L. Yancey was sent to the United Kingdom to garner support and military aid in the United Kingdom. He failed and on May 13, 1861, Britain declared itself neutral. In this neutrality declaration, the United Kingdom labeled the Confederacy as a “belligerent power.” While both the North and the South believed that this decision was coded as support for the Confederacy with this wording choice, it was not. Instead, it was just the definition that Great Britain thought best described the Confederates who had written their own constitution, mustered their own army, and controlled a large portion of North America.

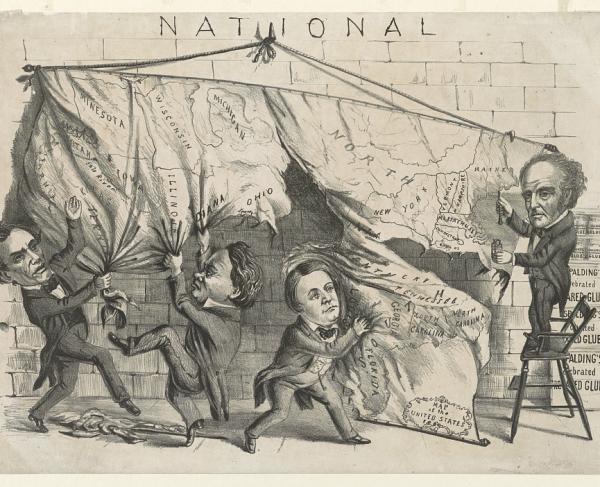

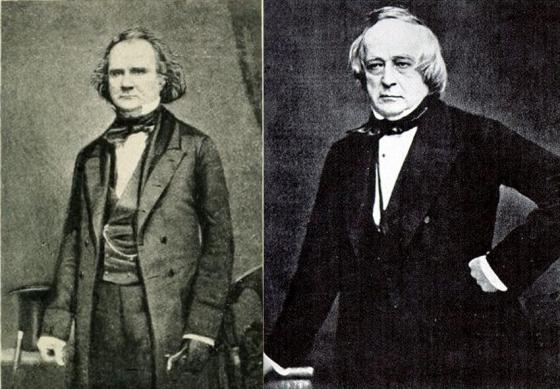

On April 19, 1861, the Union had established a blockade along the Southern shores that had limited but had not completely stopped Southern commerce. Several months later, the South enacted a self-embargo on Southern goods destroying all commerce lines with foreign entities. This embargo started the diplomatic strategy “Cotton Diplomacy.” The Confederate government tasked James Mason of Virginia and John Slidell of Louisiana to travel to England and France respectively. Once there, the delegates were to warn these foreign powers that they would never get Southern goods again unless they gave international recognition to the Confederacy.

This diplomatic expedition was labeled the “Trent Affair” after Mason and Slidell were arrested onboard the RMS Trent by Union Captain Charles Wilkes on route to Europe. This arrest, and eventually imprisonment, angered Europe because it violated international neutrality laws. The North, after several weeks, released the two Confederate diplomats and condemned Wilkes’s actions, but did not officially apologize for the diplomat’s imprisonment. Mason and Slidell, after reaching Europe, did not find sympathy in either England or France. The Confederacy was never officially recognized internationally.

During the Civil War, cotton supplies in other regions of the world started to flourish, as the self-imposed Southern embargo backfired, as bales of cotton rotted on docks and in warehouses. India, which was under the rule of Britain, increased its production of cotton by 70% in the 1860s. Brazilian cotton exports rose by 400% in this decade from 12,000 to 60,000 tons annually. Egyptian cotton also increased its distribution. There were some commercial disruption and unemployment in international cotton mills because of the Southern embargo, such as the disruption in work in North West England that resulted in the Lancashire Cotton Famine. However, cotton manufacturing and industry did not stop without these Southern goods. Ironically, textile manufacturing flourished after other cotton suppliers were found.

The “Cotton is King” philosophy proved to be faulty. The international community did not need Southern raw goods for its manufacturing industry to survive. Alternate markets were found without these countries entering a bloody Civil War or giving the Confederate States sovereignty. James Hammond’s prophecy did not come true: England did not “topple headlong” nor would the “whole civilized world” go with her.