The Navies of the Civil War

As the Civil War raged on the land, the two national navies— Union and Confederate —created another war on the water. The naval war was one of sudden, spectacular lightning battles as well as continual and fatal vigilance on the coasts, rivers, and seas.

Union President Abraham Lincoln set the Union’s first naval goal when he declared a blockade of the Southern coasts. His plan was to cut off Southern trade with the outside world and prevent sale of the Confederacy's major crop, cotton. The task was daunting; the Southern coast measured over 2,500 miles and the Union navy numbered less than 40 usable ships. The Union also needed a “brown water navy” of gunboats to support army campaigns down the Mississippi River and in Northern Virginia.

The Southern states had few resources compared to the North: a handful of shipyards, a small merchant marine, and no navy at all. Yet the Confederates needed a navy to break the Union blockade and to defend the port cities. Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory, scrambled to find ships and even took on an offensive task: attacking Union merchant shipping on the high seas.

The first task for Lincoln’s naval secretary, Gideon Welles, was a straightforward, but huge, fill-in-the-blank: acquire enough vessels to make every Southern inlet, port, and bay dangerous for trade. The Northern navy immediately began building dozens of new warships and purchased hundreds of merchant ships to convert into blockaders by adding a few guns. The result was a motley assortment that ranged from old sailing ships to New York harbor ferryboats. Critics called it Welles’ “soapbox navy.”

The Union’s blockading squadrons needed not only ships, but also bases on the Southern coast from which to operate. In 1861 the Union began a series of attacks on port cities like Hatteras, North Carolina and Port Royal, South Carolina along the southeastern seaboard. Poorly defended, they fell to Union gunnery and were seized to use as bases. Though never air-tight, by late 1862 the blockade had become a major impediment to Rebel trade.

With a smaller fleet and fewer shipyards than the North, the Confederates counted on making the ships they had as formidable as possible. They decided to challenge the Union navy with the latest technology: ironclads. Though iron-armored ships had appeared in Europe in the 1850s, Union warships were still built of wood. The first Confederate ironclad began its career as a Union cruiser, the Merrimack, captured by the Southerners when they seized Norfolk navy yard in Virginia. The Confederates ripped off nearly everything above the waterline of the ship—which they renamed Virginia—and replaced it with a casemate of heavy timbers covered by four inches of iron plating. Though underpowered and crude, as yet there was no match for her in Lincoln’s wooden navy.

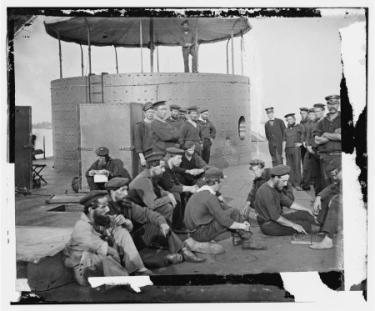

The Union quickly met this challenge with the ingenuity of inventor John Ericsson. Most of his ironclad—the Monitor—was underwater. All that appeared above board was a flat main deck and a circular housing carrying two guns. This “tin can on a raft” was the world’s first rotating gun turret, and it was protected by eight inches of iron. Monitor met Virginia in March 1862 at Hampton Roads, Virginia. Their three-hour engagement—often fought at point-blank range—was the world's first battle between ironclad vessels. The engagement itself was a draw but the very existence of Virginia deterred Union army operations in the area for some months afterwards. Suddenly the wooden naval vessel—and most of the Union fleet—was obsolete. Shipyards North and South began to turn out ironclads as quickly as possible.

Early 1862 also marked the beginning of the Union campaigns to split the Confederacy apart along the Mississippi River. A fleet of gunboats was built to support Ulysses S. Grant’s army as it moved from Illinois down the Mississippi River into the heart of the South. Most of these vessels were little more than flat-bottomed, steam-driven barges with heavy timbered sides; the most powerful, like the Cairo, were also iron plated. Grant’s army and the brown water navy captured Rebel strongholds such as Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee. At the same time, a squadron in the Gulf of Mexico, under David G. Farragut, boldly took on the defenses of New Orleans, Louisiana, with the intention of moving past the city and northward up the Mississippi River. In April 1862, Farragut’s fleet fought past two formidable forts and forced New Orleans to surrender. In July, 1863, after a series of hard-fought campaigns against both Rebel forts and fleets, these two Union forces—one moving south and one moving north—would meet at Vicksburg, Mississippi and sever everything west of the River from the rest of the Confederacy.

In April 1863, the Union navy turned with force on the Southern port cities when it took on the defenses of Charleston, South Carolina. The Confederates were well prepared—having had two years to position guns, floating obstructions and mines (torpedoes)—and the attack failed. Charleston did not fall until the war was nearly ended. After the debacle at Charleston, two other major port cities were targeted: Mobile, Alabama—the last major port in the Gulf—and Wilmington, North Carolina—the last and most important Atlantic gateway in the Confederacy. Mobile was defended by two large forts but these fell under Farragut’s assault in August 1864. In January, 1865, after a failed first attempt, the largest Union fleet ever assembled attacked Fort Fisher—the key to Wilmington’s defense—and the stronghold fell. Its loss deprived Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia of a major supply source and contributed directly to the end of the war.

While the war rumbled along on the home front, the Confederates outfitted a series of commerce raiders, vessels such as Sumter, Alabama, and Shenandoah to attack Union merchant shipping worldwide. These ships were acquired by Confederate agents in Europe and most never entered a Southern port. Alabama, under Raphael Semmes, was the most famous. Destroying over 60 ships in a 21-month cruise and sending the Union shipping interests into a frenzy, Alabama was finally confronted by the Union cruiser Kearsarge off Cherbourg, France in 1864. In one of history's last classic one-on-one sea duels, the famed Confederate raider was sunk by accurate Union gunfire.

Finally, the last official act of the Confederate States of America was a naval one. The Confederate raider Shenandoah, far at sea in Pacific waters, only learned of the Civil War’s end four months after the Confederate armies surrendered. Shenandoah finally lowered her flag in England on November 6, 1865.