A Clash of Sabres

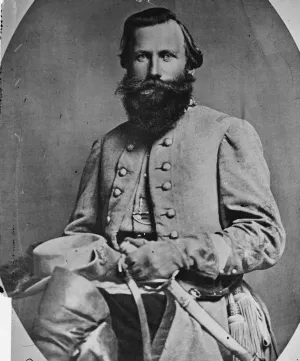

John Buford's Union cavalry gave J.E.B. Stuart quite a surprise—and an equally vigorous fight—in the fields and hills around Brandy Station on June 9, 1863.

BY DANIEL J. BEATTIE, PHD

THE ROAD TO GETTYSBURG began at Brandy Station. But the cavalry clash in Culpeper County, Virginia, counts for more than just the opening round of Lee's Second Invasion of the North. The battle showed both sides that the Federal cavalry had come of age; it signaled that horsemen Blue and Gray were now equal in ability; it refuted for good the snide remark of Joe Hooker, "Whoever saw a dead cavalryman?"

As commander of Army of the Potomac, Hooker had in fact reformed his cavalry in the early spring of 1863. He ordered the horsemen in his command concentrated into a cavalry corps, the better to perform the traditional cavalry tasks of screening their own army and finding out what Lee's army was doing. For two years, under the able J.E.B. Stuart, the Confederate cavalry had performed that role superbly, often at the expense of the Federal horsemen.

In early June 1863, Hooker ordered his Cavalry Corps commander, Alfred Pleasonton, to take most of the Union cavalry up the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg to Culpeper County. Hooker had learned the Confederate cavalry, and possibly some of Lee's infantry, were massing in that region of plentiful forage and plentiful strategic opportunities. Either Stuart meant another large-scale cavalry raid, or he was the vanguard of another thrust by Lee at Washington or Northern soil. Hooker instructed Pleasonton "to disperse and destroy" Lee's mounted arm.

War had visited Culpeper's woods and rolling fields several times in the preceding two years. Armies had marched through it, camped there, sparred with each other there, and fought there in the battle of Cedar Mountain in 1862. Dismantled fences, missing livestock, ruined roads, embittered civilians, and the fresh graves of local boys were the price Culpeper had paid so far in the War for Confederate Independence. In early June 1863, war came calling again.

The Confederate cavalry was ready for war that spring. In late May and early June, Stuart staged several magnificent cavalry reviews in Culpeper. Never before were Lee's horsemen so numerous, so confident, so ready. Lee indeed meant to carry war across the Potomac. Stuart's 9,700 troopers would lead the advance across the Rappahannock and mask the army's approach to the Potomac. Stuart was set to cross the Rappahannock early on June 9, the day after the last grand review, at Beverly's Ford.

Another great cavalry force also planned a crossing at Beverly's Ford that morning. A column of 4,500 cavalry and 1,500 infantry wearing Union blue and towing 16 cannon arrived at the Rappahannock first. This imposing force crossed without much opposition and gave Jeb Stuart his first great shock of the day. Alfred Pleasonton was also surprised. He had expected to find Stuart's men near Culpeper Court House, ten miles from the river.

The Federal commander had divided his force in two. Another Union column, about the same size as the wing at Beverly's Ford, was supposed to cross the Rappahannock at Kelly's Ford, eight miles downstream at dawn. The two columns were to join at the village of Brandy Station before proceeding against Stuart. It was a reasonable plan, since Brandy was no more than eight miles from either ford, except that Stuart's cavalry was around Brandy.

Stuart recovered quickly from the surprise. He dismantled his headquarters on Fleetwood Hill and dispatched couriers to his brigades. He ordered the part of his command nearest the river to pull back to a low ridge near a little brick church dedicated to St. James. He was unaware at first of the second threat from Kelly's Ford.

Stuart was not the only Confederate taking actions that would dramatically shape the battle. Closer to Beverly's Ford, Rebel soldiers scrambled to their horses or artillery pieces. The 6th and 7th Virginia Cavalry and one cannon from South Carolina bought time along the Beverly's Ford Road while Stuart's battalion of horse artillery fell back and his brigades assembled.

The best Union cavalry general, John Buford, led the Yankee attackers at Beverly's Ford, though corps commander Pleasonton accompanied the column. It took Buford over three hours to sort out the confusion of the initial contact, finish the crossing, and deploy his force. Though he had no word from the other wing, under General David McMurtrie Gregg, Buford elected to launch a bold attack on the Confederate center.

At about 8:00 a.m., with textbook discipline and uncommon valor, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry surged across an open field toward sixteen Confederate fieldpieces belching canister. The 6th Pennsylvania was ably supported, by the 6th U.S. Cavalry. But the Confederate artillery was also supported: by nearly 5,000 mounted and dismounted cavalry. The gallant charge shattered on the defenders' line.

Apprehending the strength of the Confederates at St. James Church, Buford left four cavalry and two infantry regiments to hold against Confederate attacks and guard the vital ford. He then took his remaining men northward to work his way around the Confederate left flank. On the Cunningham and Green farms, Buford was opposed by Rooney Lee's brigade. In vigorous mounted and dismounted fighting, Buford gradually forced Lee back to Yew Ridge and northern Fleetwood Hill. Stuart, however, was now pressing the line Buford had left in front of St. James Church. Both sides anxiously awaited reinforcements. Stuart needed Thomas Munford's brigade from across the Hazel River. Buford wondered where Gregg was.

The morning had not gone smoothly for Gregg, whose column consisted of his own division, that of Colonel Alfred Duffie, and an infantry brigade. He found no Confederates guarding Kelly's Ford, but Duffie's command became lost. The frustrated Gregg got all his men over the river by 9:00 a.m., four hours late. For four hours cannon fire rumbled in the distance.

Gregg sent Duffie's men westward to check the Fredericksburg road near Stevensburg for signs of infantry. Since a small brigade of North Carolina cavalry blocked the direct route to Brandy Station, Gregg took a roundabout road that brought him to Brandy by eleven.

Ahead was Fleetwood Hill, unoccupied except by one Confederate fieldpiece bombarding his lead brigade. Fearing a trap, Gregg carefully deployed his troops before seizing the hill.

The eruption of Union forces from Brandy Station, in the Confederate rear, was the second great surprise of the day for Stuart. Nevertheless the Southern leader acted decisively, even brilliantly. Pulling most of his regiments from the St. James line, he sent them galloping for Fleetwood Hill, a mile away.

While Gregg and Stuart raced for the key piece of terrain on the battlefield, two Southern regiments stalled Duffie's 2,000-man division near Stevensburg. Oddly indecisive, Duffie failed to participate in the rest of the action that day.

The battle came down to a struggle for Fleetwood Hill, a contest that consumed the afternoon. The Confederates reached the grassy crest first with cavalry and artillery and poured down the reverse slope upon the Yankees. The hilltop changed hands several times. The battle seemed to devolve into a giant, swirling melee. Men of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Maine struggled with Virginians, Georgians, Carolinians, and Mississippians.

By late afternoon the Federals had used up all their reserves. Though Buford continued to press back the Rebels on northern Fleetwood, the southern part of the hill, more than a mile away, was held by exhausted but triumphant Confederates. Then Munford's fresh brigade at last arrived on Buford's flank and rear. Pleasanton saw that further effort was fruitless and ordered his subordinates to recross the Rappahannock.

As such things are measured, the Confederates had won the battle: the Stars and Bars flew on Fleetwood Hill and near St. James Church, while the Stars and Stripes retreated. In fourteen hours of fighting Stuart had lost about 500 men killed and wounded, the Federals about 900. Small numbers compared to the terrible toll of Gettysburg, three weeks later. Yet many veterans who rode and fought over Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia during the next two years remembered Brandy Station with pride as the largest and most hotly contested clash of sabers in the long and bloody war.

Daniel J. Beattie is a historian and writer from Charlottesville, Virginia.

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...