Custer's First Last Stand

LIEUTENANT GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT WAS THE MASTER OF THE STRATEGIC RAID, on several occasions using his cavalry to create havoc in the Confederate rear and divert the enemy's attention.

In May 1864, Grant tried the tactic again when he unleashed the Army of the Potomac's Cavalry Corps on a raid deep into the heart of Virginia. The "Richmond Raid," as it is known, drew off the entire Confederate cavalry force and climaxed with the great battle of Yellow Tavern, fought May 11. The great Confederate cavalry chieftain, Major General J.E.B. Stuart, was mortally wounded during the battle. With his eyes and ears gone, Robert E. Lee did not detect the withdrawal of the Army of the Potomac from the lines around the Wilderness, and only won the race to the strategic crossroads of Spotsylvania Court House through good fortune and hard marching.

After two weeks of slugging it out along the trench lines at Spotsylvania Court House, the Army of the Potomac again broke contact and moved around Lee's flank toward the North Anna River. Lee nearly drew the Union army into a trap on the banks of the North Anna, but the Northerners escaped and moved toward Cold Harbor, northeast of Richmond. After several more bloody days of fruitless frontal assaults at Cold Harbor, Grant realized that the geography of the area around Richmond was hemming him in and that his campaign was bound to bog down on the Peninsula much as Major General George B. McClellan's Peninsula Campaign had in 1862.

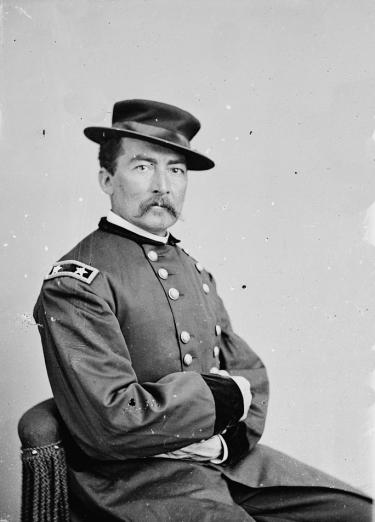

Grant ordered his Cavalry Corps commander, Major General Philip H. Sheridan, to lead another strategic raid intended to distract the enemy from his real intentions, which were to slip across the James River and move on Petersburg. Sheridan was to take the First and Second Cavalry Divisions, march west, and destroy the Virginia Central Railroad at Charlottesville, Lynchburg, and Gordonsville Then his orders were to link up with Major General David Hunter and bring Hunter's army east to join the body of the Army of the Potomac. On the return trip, Grant directed, Sheridan was to remain on the course of the railroads until "every rail on the road destroyed should be so bent and twisted as to make it impossible to repair the road without supplying new rails" until the raiders were "driven off by a superior force." If the audacious plan succeeded, the Army of Northern Virginia would be cut off from the granary of the Shenandoah Valley.

While Sheridan was off on his raid, Grant planned for the Army of the Potomac to disengage from Lee's army, steal a march across the James River and invest Petersburg, while Brigadier General James Wilson's Third Division screened its advance. If all went as predicted, Grant would take Petersburg before Robert E. Lee even detected the movement of the Union army. In addition to the destruction of Lee's lifeline to the Shenandoah Valley, Lee's army would also be cut off from the Deep South. The Army of Northern Virginia would either have to surrender or come out and fight the combined Union armies on ground of Grant's choosing.

The plan was fraught with risk. After studying the lay of the land, Sheridan decided to march 60 miles along the north bank of the North Anna River to cross at Carpenter's Ford, striking the Virginia Central six miles west of Louisa Court House at Trevilian Station. Little Phil intended to destroy the Virginia Central between Louisa and Trevilian Station, march past Gordonsville, strike the railroad again at Cobham's Station, and destroy it from there to Charlottesville. Once he reached Charlottesville, he would link up with Hunter. The march west would cover nearly 100 miles.

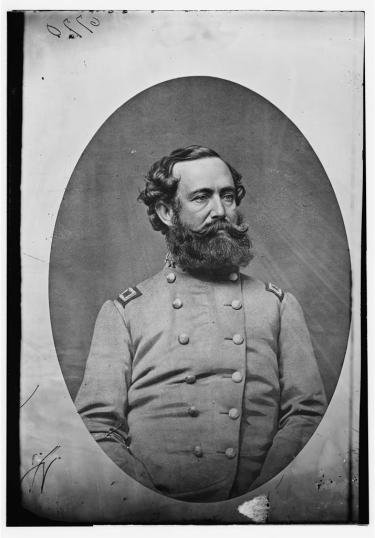

Sheridan departed on June 7. Confederate scouts quickly detected Sheridan's march and reported the movement to Major General Wade Hampton. General Robert E. Lee ordered Hampton to take two divisions and follow the Union forces. Choosing Major General Fitzhugh Lee's division in addition to his own, Hampton marched with 6,000 sabers and four batteries of horse artillery.

Guessing that Sheridan's objectives were the crucial railroad junctions at Charlottesville and Gordonsville, Hampton realized that he would have to move quickly. Sheridan would have nearly two full days' head start, so the Confederates would have to move fast to make up lost ground if they were to have any hope of intercepting Sheridan. About 3 a.m. on the morning of June 9 the Confederate troopers swung into their saddles and moved out at a steady walk with Hampton's division in the lead. The Confederate cavalry covered 30 miles that day. Sheridan, blissfully unaware that his column was being pursued, got a relatively late start and covered only 24 miles that day. That afternoon, a contingent of Sheridan's scouts captured some of Hampton's outriders, who informed their captors of the Confederate pursuit.

The chase continued the next day when the Confederates broke camp at 2 a.m. Lee's Division marched to Louisa Court House and halted there while Hampton's Division continued on for another four or five miles, passing Trevilian Station to cover the main roads that connected Louisa to Gordonsville and Charlottesville. Hampton's forced marches had enabled his men to get across Sheridan's intended line of march, and the Union chieftain was unaware that the Confederate horse soldiers were there. Hampton sent out pickets, feeling for the Northern advance elements.

Hampton real chance to catch Sheridan unawares; he planned to attack at dawn.

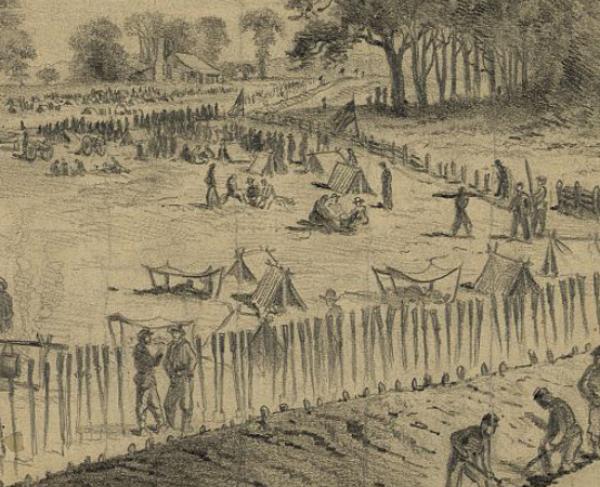

Sheridan's long column snaked across the countryside, crossing the North Anna at Carpenter's Ford as he had planned. The Northerners pitched their camps near Clayton's Store, at the intersection of the Marquis Road and the road to Carpenter's Ford. Brigadier General George A. Custer's picketed the Marquis Road, holding a critical position on the banks of Nunn's Creek. Hampton and Sheridan both planned movements for the next morning. Sheridan intended to move at sunrise. Brigadier General Alfred T. A. Torbert's division was to converge on the railroad depot from two directions. Brigadier General Wesley Merritt's Regulars and Colonel Thomas C. Devin's troopers would advance along the Fredericksburg Road while Custer's Wolverines would take a wood road atop a ridge line, reportedly a direct route to the train station. Torbert's brigades would reunite at the train station while Brigadier General David M. Gregg's division brought up the expedition's wagon train and guarded the flanks.

Hampton realized that he had a chance to catch Sheridan unawares; he planned to attack at dawn. His division would advance north along the Fredericksburg Road toward Clayton's Store, while Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser's Laurel Brigade covered the left flank along the Gordonsville Road. Lee would march up the Marquis Road from Louisa, covering the right flank. The two divisions would unite near Clayton's Store, pinching Sheridan's command between them and pinning the Northern horsemen against the banks of the North Anna.

The plan was simple, but it failed to account for the fact that Sheridan's men also had orders to move out early that day. At dawn, elements of the Union and Confederate forces met along the Fredericksburg Road to the north of the train station and heavy fighting broke out — fighting that lasted the entire day. Colonel Gilbert J. Wright's Georgians, who had been guarding Hampton's wagon train in the fields surrounding Trevilian Station, were pulled out of their position to join in the fighting on the Fredericksburg Road.

Meanwhile, Custer set his brigade marching down the Nunn's Creek Road about 6 a.m. When the Wolverines, led by Colonel Russell A. Alger's 5th Michigan, arrived at the intersection of the Nunn's Creek Road and the Gordonsville Road two hours later, they could hear the fighting that raged along the Fredericksburg Road. Custer sent Alger's unit forward to reconnoiter toward the train station. An officer of the 5th Michigan sent back word that a large Confederate wagon train lay unguarded, just to the east of Trevilian Station. Recognizing an opportunity to capture a sparkling prize, Custer ordered the entire 5th Michigan to charge the wagon train. Alger, a prominent lawyer and lumberman, drew his saber with a yell and charged the wagon train, his regiment in tow. Swooping down on the defenseless wagon train, Alger's men bagged several hundred prisoners, 1,500 horses, a stand of colors, six caissons, 40 ambulances, and 50 army wagons. Custer then committed the 6th Michigan to the charge.

As Custer consolidated his prize, word reached Hampton that a large force of Yankees had gained his rear and captured his wagons. Reacting quickly, Hampton called for Rosser's Laurels, and began consolidating his lines around Netherland Tavern. He sent two regiments to charge the Yankees and another two regiments to reinforce the position near the station. Hampton also sent a messenger to Lee with orders to join Hampton as soon as possible. Lee did not come quickly.

Rosser did not wait for orders. Hearing the commotion, Rosser called his brigade forward at a gallop. Flying back down the Gordonsville Road toward the train station, Rosser found that Custer had failed to picket the road and that his route of advance was clear. With Rosser leading the attack, the screaming Laurels drew sabers and pitched into Custer's ranks with the 11th Virginia and the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry leading the way. Rosser spotted his old friend and rival, Custer, calmly barking orders as the fighting whirled around him Major Holmes Conrad, one of Rosser's staff officers, drew a bead on Custer's color bearer, Sergeant Mitchell Beloir and shot him down. The mortally wounded sergeant made his way to Custer, saying, "General, they have killed me! Take the flag!" Custer later lamented in a letter to his wife, "To save it, I was compelled to tear it from its staff and place it in my bosom." There, Custer would carry it for the rest of the day's fighting.

The charge of the Laurels shattered Custer's thin line and drove it back. The hard-charging Laurels recaptured the wagon train and cut off Alger and a small band of 40 officers and men. Only quick thinking by one of Alger's staff officers kept them from being captured when a Confederate officer asked them, through the dense underbrush, what command they belonged to. The staff officer replied, "Hampton's." Alger and a dozen men made their way back to the regimental camp that night after a day of wandering and trying to avoid the enemy. The other 28 men, left to their own devices, spent two weeks hiking across hostile territory before making their way to safety. Rosser's charge swept up more than half of the men of the 5th Michigan.

Wright's Georgia brigade joined the Laurels in attacking Custer. The gunners of Lieutenant Alexander C. M. Pennington's Battery M, 2nd U.S. Artillery, tore down a stout wooden fence and unlimbered. Their severe fire blunted Rosser's attack and brought the Laurels to a screeching halt about a mile to the east of the station.

As the fighting swirled around him, Custer was seemingly everywhere. He rescued a badly wounded trooper of the 5th Michigan while under heavy fire, and was badly bruised by two spent balls that did not break the skin. The officer responsible for the wagons asked Custer if he could take his prize to the rear. The distracted Boy General said, "Yes, by all means." Relieved, the officer left to lead the wagons to safety. As he rode off, one member of the 7th Michigan heard Custer inquire, "Where in hell is the rear?"

Fitz Lee's lead elements eventually joined the fray. Soon, the Wolverines were completely surrounded, hemmed in, "on the inside of a living triangle." Brigadier General Lunsford L. Lomax's Virginians led the way, recapturing nearly all the wagons, five of Pennington's caissons, Custer's headquarters wagon, and his personal cook. The Virginians also snapped up Custer's adjutant general, Captain Jacob L. Greene. Four Confederate brigades squeezed Custer's lone brigade. They captured one of Pennington's guns, and only a determined attack led by Custer himself saved it. Custer wrote, "The enemy made repeated and desperate efforts to break our lines at different points, and in doing so compelled us to change the positions of our batteries." As one witness recalled, "For a time there was a melee that had no parallel in the annals of cavalry fighting in the Civil War. Custer's line was in the form of a circle and he was fighting an enterprising foe on either flank and both flank and rear."

Only a timely attack by three brigades of Federal cavalry saved Custer's Wolverines from total destruction. The relief column finally slashed its way through to the Michigan men, freeing them from their trap. Hard fighting by the Wolverines and Custer's legendary good luck had barely saved his brigade from utter destruction at the hands of the Confederate horse soldiers. As it was, the Michigan Brigade suffered 11 killed, 51 wounded, and 299 captured, for total losses of 361, including half of the 5th Michigan. However, unlike another June day twelve years later, Custer received reinforcements that rescued his beleaguered command from its trap. And, unlike that hot dusty day in June 1876, George Custer had survived his "first last stand."

Related Battles

950

1,000