Devil's Den & Little Round Top: Then & Now

In 2010, the Civil War Trust saved a 2 acre section of the Gettysburg batlefield - ground that is closely associated with Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's attack on the Union left on July 2, 1863. To learn more about this pivotal attack and the state of the battlefield today, the Trust turned to "Second Day" experts Garry Adelman and Tim Smith.

Civil War Trust: Much has been made about the fractious disagreement that James Longstreet and Robert E. Lee had about the offensive opportunities on July 2, 1863. What fueled this disagreement and did it have any material impact on the fighting to come that day?

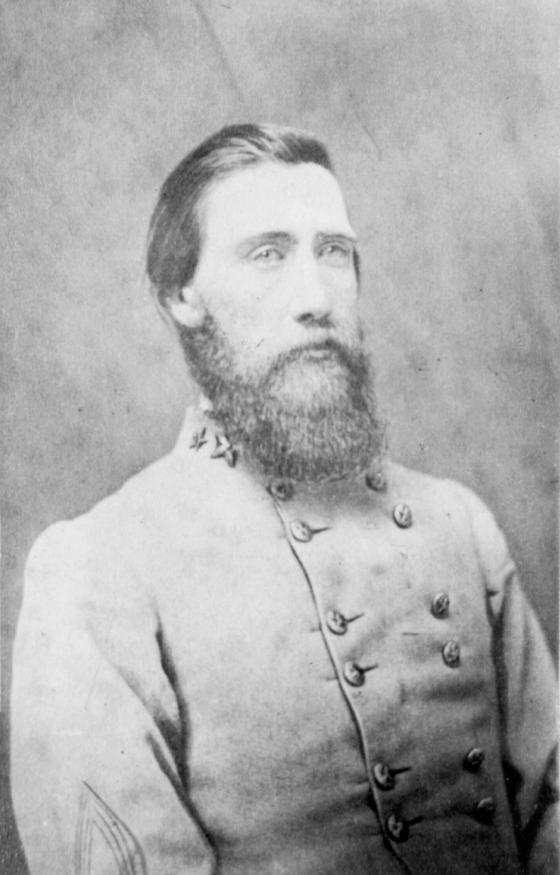

Garry Adelman: Lee and Longstreet fundamentally disagreed about what was the best course of action after the battle of July 1. Longstreet still labored under the impression that the entire campaign was to be fought as a “tactical defensive” while Lee, given the Confederate success on the First Day, felt that the “aggressive” was in order. Longstreet suggested a very wide movement around the Union army to interpose the Confederates between Meade’s Yankees and Washington, and later proposed a tighter movement around the Union Army. One of Longstreet’s subordinates, John Bell Hood, favored a still tighter movement around the enemy left—one that would take his division of 7,000 men behind Little Round Top and into the Union rear.

Longstreet and Hood’s objections did not change Robert E. Lee’s orders for Longstreet to not only attack but to attack “up the Emmitsburg Road.” But interestingly, Hood, whose division attacked first and therefore the rest of Longstreet’s force, attacked in a more easterly direction than ordered by Lee. Therefore, what was ultimately implemented was something in between Lee’s orders and Hood’s desires.

When one looks at the rocky and broken terrain of Devil’s Den and Little Round Top it’s hard to imagine a more difficult location for an attack. Did the Confederates have a good sense of the terrain before them on July 2nd?

GA: Some Confederate scouts reported to have examined the ground around the Union left flank and reached the slopes or summit of Little Round Top before the fighting started on July 2nd. Whether the nature of the rugged terrain was reported to the Confederate high command, it did not change Lee’s orders for the attack and that attack did not include plans for Confederate movements at Devil’s Den or up the slopes of the Round Tops. The Confederates as ordered by Lee would not have traversed the Snyder, Sherfy and other properties, avoiding the most difficult terrain anyway so it’s almost a non-issue. John Bell Hood later wrote that the Union position was so strong as to render it impregnable by Union troops simply rolling down loose stone sand boulders upon the hapless Confederates. This is among the reasons that Hood says he objected to attacking Little Round Top. But, by the time the attack truly developed, Hood was wounded and decisions were made and orders issued at the regimental and brigade level.

One of the most common complaints of the Confederate offensive plan versus the Union left is that the Confederate army could have/should have swung around the Union position at Little Round Top, thereby avoiding a difficult defensive position. What’s your take on this argument?

GA: As mentioned above, there were various iterations of this plan. The wider swings were Longstreet’s and the tighter swing was Hood’s. Both suggestions were risky and in our opinion, flawed. The wider sweep around the Union army was full of uncertainty, would have taken substantial time, and would have to have been made without Lee’s best cavalry units. The tighter swing, Hood’s, was even riskier. Hood had 7,000 men and he proposed to detach from the rest of the army and cause trouble in the Union rear. Surely, he could have caused trouble, but then what? General Meade had already ordered his entire Fifth Corps of 10,000 men followed soon after by a similar number from his Sixth Corps. These two Union Corps were ordered to the left and to hold that position at all hazards and they approached the left in a manner that would have blocked Hood’s path or worse-- emerged directly upon Hood’s flank.

Our take on these alternate plans is that both Hood and Longstreet advanced risky plans at Gettysburg and also buttressed the viability of these plans after Lee’s death. As both Longstreet and Hood later found at Knoxville, Suffolk, Franklin and Nashville, implementing plans as an army commander is a much different animal than doing so as a subordinate.

For so many modern visitors, their understanding of the fighting at Little Round Top on July 2nd is heavily molded by the 1993 movie “Gettysburg.” How does that cinematic account match the true fighting on this section of the battlefield?

GA: The Gettysburg movie is based upon the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Killer Angels. The problem in this case with The Killer Angels, and thus the movie is not so much with its being a novel and associated lack of factuality (and trust us, there is plenty) but the matter of focus. There were 118 general officers at the battle of Gettysburg and The Killer Angels focuses upon four. Of the more than 400 infantry regiments at Gettysburg, The Killer Angels, and therefore the movie, and to an even greater extent the Ken Burns PBS series focuses upon one—The 20th Maine and Joshua Chamberlain. Therefore, in the book and the two productions Little Round Top becomes the most important part of the story—all spend more time on this action than the entire First Day and the rest of the Second Day combined! Never mind that the fighting at the Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard and other places were larger and bloodier affairs than Little Round Top.

At least ten Union and five Confederate regiments took casualties on Little Round Top and some of these casualties were part of actions every bit as important as those on the far left flank of the Union army—the position of the 20th Maine. Most of the other Union regimental commanders on Little Round Top, however, were dead within one year. Therefore, who was left to tell the story of Little Round Top--dead officers or a great writer, a professor, a later Medal of Honor winner—Joshua Chamberlain? This is not to say that the 20th Maine’s actions were not important. Rather it is to say that many other units on Little Round Top performed deeds just as important.

The book, movie and documentary also continued another unwarranted trend—that of elevating the military importance Little Round Top above the already-exalted position it deserves. I was actually so worked up about this issue that I wrote a book entitled, The Myth of Little Round Top, just to lay out the problems with the popular story of the fabled hill.

The region of the Gettysburg battlefield associated with the second day’s fight is rich in Civil War photographic history. As part of your in-depth research of Civil War photography in this region what are some of the more interesting events and finds that you have come across?

GA: There are too many to discuss here! The main ones that come to mind, of course, are the key discoveries and research in William A. Frassanito’s body of Gettysburg work. “Fraz” is the undisputed Dean of Civil War photographic research and his work on the Second Day’s death studies at the Rose Farm and Slaughter Pen must stand out as some of the most important contributions to the understanding and use of Civil War photography—a field he pioneered, if not created. Other Second Day areas within his focus were Little Round Top, the Trostle farm, the Devil’s Den, and the Wheatfield area.

But a cadre of other historians and enthusiasts, most of whom are Center for Civil War Photography members or board members, has taken up the torch, locating hundreds of additional views for more than twenty years. It is this ongoing work, solving Gettysburg’s photo mysteries, that captures our attention and helps to maintain our passion for the subject. We ourselves have found the locations of scores, if not hundreds, of Second Day views ranging in date from 1863 all the way into the 20th century. Avid Gettysburg collector and guide Sue Boardman has made significant contributions to the study. Last year, Tom Danninger found the location of an 1867 stereoview which had supposedly been recorded at Devil’s Den but was in fact at the Devil’s Kitchen. His discovery transformed that image into the earliest known image of the Devil’s Kitchen, by decades. Just last fall, Barry Martin discovered the location of a view near Big Round Top that had eluded many of us (and caused many historians to simply guess) for more than 15 years! Determining the location of even postwar views can significantly enhance our understanding of the battle and battlefield. And there are plenty of Gettysburg photo mysteries remaining and we always encourage people that it’s not at all too late to get in the game. Just bring your favorite accounts and images out to historic sites and enjoy!

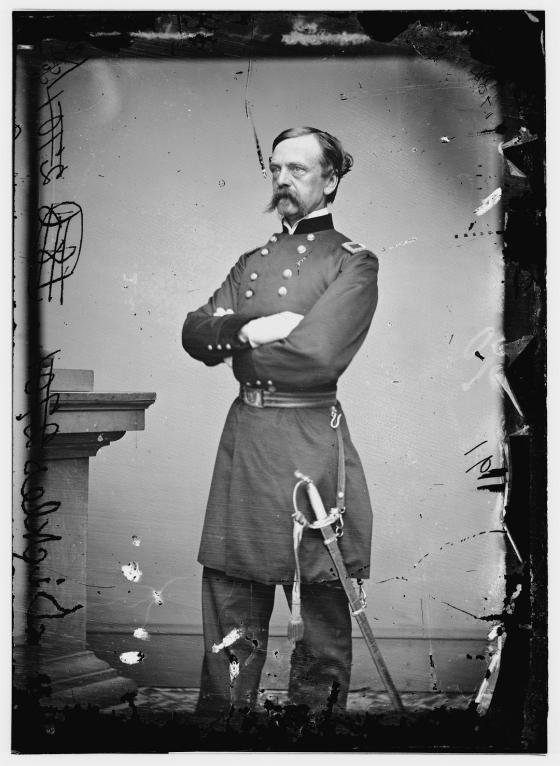

Much ink has also been spilled in the debate over Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’ actions on July 2, 1863. Why did Sickles move his Union Third Corps so far forward and was this movement at odds with Meade’s orders?

Tim Smith: In the years following the battle, Daniel Edgar Sickles, spent a large amount of time and effort to cloud the facts surrounding his forward movement. And today, the historic record provides no clear explanation for his actions on July 2nd. There are far too many historians that place credence in the value of his forward movement. Let us be clear. His movement was absolutely against orders, and it totally disrupted the plans of the Union Army commander that day. Sickles supporters often argue that his forward movement, forced Meade into creating a defense in depth, which ultimately slowed the Confederate attack and led to the Northern victory at Gettysburg. But, in fact, Sickles movement left Little Round Top unoccupied, and created a dangerous gap between the Union 2nd and 3rd Army Corps. In the end, it was not Sickles movement that slowed the Southerners, his men were routed and driven back at every point. It was the 20,000 reinforcements that General George Gordon Meade pumped into the area that forced the issue and ultimately defeated Longstreet’s attack.

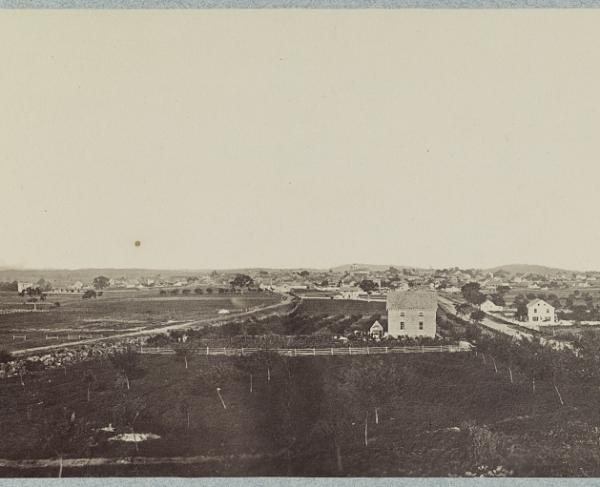

Unlike many Civil War battlefields, Gettysburg, and particularly the region around Little Round Top and Devil’s Den, became an instant tourist attraction. What was the tourist experience like in the early post-war years?

TS: Unlike many areas, where Civil War battles were waged over non-descript farm fields, the region of Devil’s Den and Little Round Top has its own distinctive appearance. One might argue, that had a battle not been fought there, these places would still be well known, and that there might be some kind of local park there today The is evidence that the area was popular with locals a picnic destination even before the battle. When visitors arrived to tour the field after the war, the fact that these places were the scenes of heavy fighting only increased their interest.

The Devil's Den has fascinated many a visitor over the years. How did this area get its name?

TS: It is fascinating that we wrote a book on Devil’s Den over ten years ago, and today, we are no closer to the answer of that question. There are still are no reference of any sort that predate the battle that make mention of that place name. Since our book, several more early references have been discovered. Of course, that evidence is conflicting and confusing and it could be that the term Devil’s Den actually was being used to refer to area of Little Round Top. And it may be that some local was using the reference in some form to describe an area of rocky ground south of Gettysburg. One thing is for sure, the reason that the term became popularized following the battle, and the reason that we refer to that particular group of rock as Devil’s Den today, is historian John Bachelder. At some early point, following the battle, he became aware of the place name, and his usage of the name on his maps and in his lectures led to the terms popularity. Bachelder died in 1894 and a short time later the Gettysburg National Military Park Commission placed a cast iron plaque in front of those rocks with the words “Devil’s Den,” on it.

The both of you have given numerous tours of the Devil’s Den and Little Round Top. What are some of the more interesting, and lesser known, features that you show visitors?

TS: I think many tourist are surprised to learn that there was heavy fighting at the den. While the battle action at Little Round Top has received a considerable amount of attention, especially in recent years, the action at Devil’s Den has not. Over the years, so much attention given to the lore of the sharpshooter, or the eerie unnatural appearance of the rocks themselves. that sometimes the fierce fighting that occurred there on the afternoon of July 2, 1863 gets lost in the shuffle. Beyond that, visitors are fascinated to learn that Little Round Top and Devil’s Den was once the scene of amusement parks, photographic studios, a restaurant and an electric railway. They are fascinated that carving of early visitors once covered the rocks and some are still visible today. Tourists are often surprised that the area was just as popular 100 years ago as it is today.

Over the past ten years or so has the battlefield associated with Longstreet's July 2nd attack changed much? How would it compare to its 1863 state?

TS: We first started giving tours of the Devil's Den to large groups almost twenty years ago. We would stand atop Houck’s Ridge near the monument of the 99th Pennsylvania, and would discuss how the Confederate line of battle formed along Seminary Ridge and crossed open fields in their advance. As we discussed the battle, our groups would stare into the woods a few hundred yards to the west. And on many occasions we would point to those woods and make strong statements urging for the removal of the non historic growth particularly on that section of the field. So in some respects, we feel responsible for generating support for the parks efforts to restore that area of the field. And the National Park Service has taken a very aggressive approached in its efforts of restoration in recent years, and much of the non historic woods have been removed. I think that many of the historians of the battle are greatly interesting the appearance of the field as it was in 1863, but it is not always an easy proposition to restore an area. The accounts of the solders are rarely of use in determining wood lines and photographic evidence does not exist for every portion of the field The Warren map is particularly frustrating and confusing in its representation of rocks and trees. It is difficult, for example, to distinguish between a wood lot and an area of scrub or brush. For our own part we continue to study the evidence and help arm historians of the battle, and the National Park Service with the best understanding of the 1863 appearance of the field as possible, and assist in their restoration efforts in any way we can.

Looking into the future what sort of battlefield developments or improvements would you like to see at the Gettysburg battlefield?

TS: Just in our lifetime there have been vast and sweeping changes to the battlefield itself and the way the field has been interpreted. And though much is positive not all of the changes are good. There continues to be commercial and developmental pressures placed upon the park itself and the areas just outside of its boundaries. There is still much valuable land, that is not included within the Gettysburg National Military Park boundary. Awareness and education is very important. One of the most often used expressions by those wishing who destroy historic ground is “we didn’t know.” Wayside exhibits need to placed at sites of historic interest, so people are aware that some event occurred there. This in itself would act as a deterrent against development. Personally, I would like to see the area of every skirmish during the Gettysburg Campaign marked and preserved. Make no mistake, if we don’t preserve these areas, they will be developed.

Within the park itself, one of my pet ideas, is to have marked the site of every farm house on barn on the battlefield. The structure that no longer stand could be indicated by a large iron framework outlining the building. You could look through them, but would know and understand a building of some proportion was there. We have the knowledge of the building and know where they stood. Along with the restoration of orchards, wood lots and farm lanes, a project such as this could add immeasurably to the 1863 appearance of the field.

Related Battles

23,049

28,063