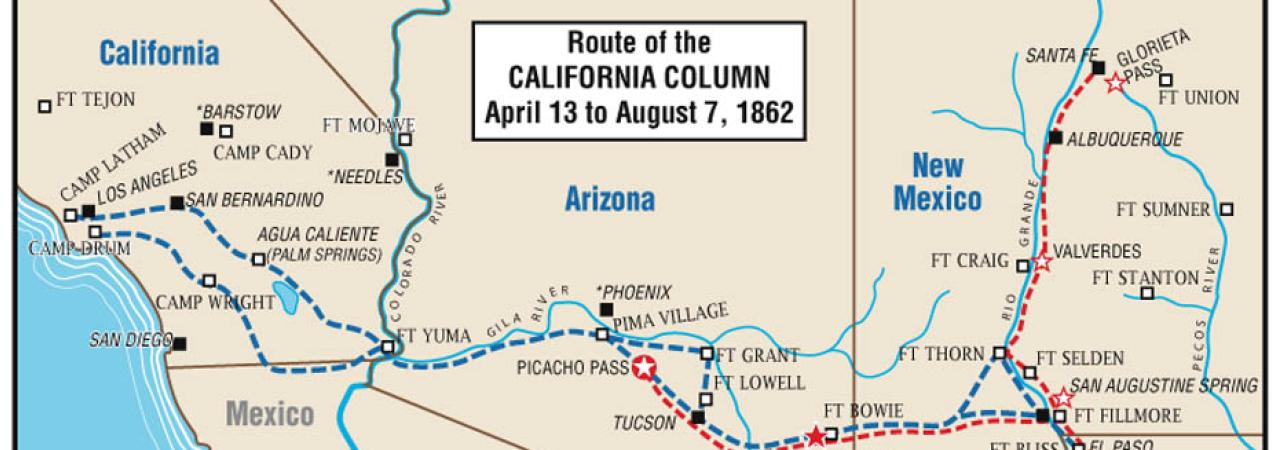

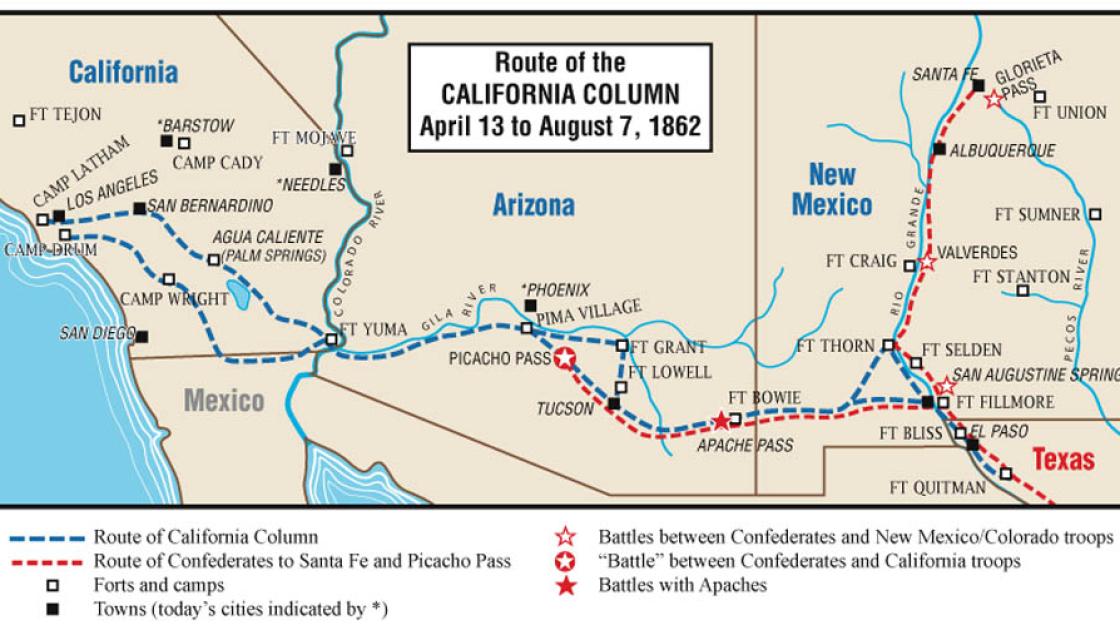

In 1862 the California Column took this route through the Arizona territory into Texas.

As the secession movement gained momentum, the question of loyalty arose in the western half of the United States. While California had already elected to become a free state in 1849, and was admitted into the Union as such in 1850, many Southerners who had migrated to California during the Gold Rush were in favor of Southern California seceding as an independent slave state separate from Northern California.

As southern sympathy grew stronger, the state of California had difficulty gaining control of its state militias. In an effort to secure the counties with high pro-Southern Democratic populations, certain militias with split loyalties were disbanded in favor of pro-Union militias.

To counteract the Union militias and to reinforce the Confederate presence in Southern California, the secessionist Los Angeles Mounted Rifles were created. While the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles were never able to rally the state of Southern California into secession, their presence alerted the Union to Confederate tendencies in the westernmost part of the country.

The Confederate movements in the western United States, especially in Arizona, brought about the creation of the California Column, a column of ten Californian companies: five companies of the 1st Regiment California Volunteer Cavalry, Company B of the 2nd Regiment California Volunteer Cavalry, and Light Battery A of the 3rd United States Artillery. The California Column contained 1,500 men, and Lt. George Pettis of the 1st California Infantry described them as “well trained, well disciplined, and eager to show what stuff they were made of.”

On March 29, 1862, the California Column had their first engagement with Confederate troops at the Battle of Stanwix Station. The Californians, under the command of James Henry Carleton, were about to begin a march from California to the Rio Grande River to occupy Arizona and drive the invading Texan Rebels out of the territory. A detachment of the California Column arrived at Stanwix Station to find a small group of Confederates burning hay that had been left at the station for the Column’s horses.

A brief exchange of gun fire between the small group of Confederates and the much larger California detachment ensued, and one member of the California Column was wounded. Although the fight was only a skirmish, it had a significant impact on the Column’s march. The destruction of hay at Stanwix Station and a number of other locations greatly delayed the march which provided the Confederates with enough time to warn the Confederate headquarters in Tucson, Arizona of the approaching Union force.

In April, the Californians’ march through Arizona to El Paso, Texas was in full swing. The Column began its march in Wilmington, California and had 900 miles of desert to cross before arriving at the Rio Grande River. The men of the California Column combated the threat of dehydration by marching in small detachments, similar to the one that fought at the Stanwix Station, in an effort to preserve their water supply. Their efforts proved to be successful, and throughout the 900 mile march, no soldiers died of non-battle causes, an impressive feat during a war that claimed nearly 250,000 non-battle casualties.

While the soldiers may have survived the elements, the march was not without conflict and loss. As a result of their delay at Stanwix Station, the Rebels had enough time to warn the Confederate command in Tucson of the impending Union march to rid Arizona of Confederate control. This information allowed the Confederates to strategically place pickets along the Column’s route to the Rio Grande.

On April 19, 1862, a small dispatch of twelve Union cavalrymen were screening for Confederate pickets when they came across a squad of ten Arizona Confederates. While the Union troops were told not to engage until the rest of the Column arrived, the Federals fired upon the Rebels and a small skirmish began.

Three of the Confederates surrendered early in the skirmish and as Lt. James Barrett, in command of the Union scouts, was loading a prisoner on his horse he was shot in the neck and killed instantly. Without a commander, the Federals retreated and the skirmish resulted in 3 casualties. While the battle was considered a Confederate victory, the Confederate forces in the area retreated to Texas shortly after, leaving the area open to the Union. The engagement has passed into history as the Battle of Picacho Peak.

Limited water supply and Confederate pickets were not the only dangers the Californians faced during their long march to Texas. Following the start of the Civil War, two Apache leaders, Mangas Coloradas and Cochise, formed an alliance to drive all Americans out of the Arizona territory.

On July 15, a detachment of the California Column led by Captain Thomas Roberts was attacked by a group of 500 Apache warriors under the command of Mangas Coloradas and Cochise. After the initial attack, the Union forces were able to regroup and unload their howitzers. Once Roberts was able to get his artillery to an advantageous spot above the Apache defenses he unleashed heavy fire, causing the Apache to flee.

When the California Column finally arrived at the Rio Grande, the Texans had already retreated. Through their 900 mile march, the Column only faced Confederate forces once and spent the remainder of their service in continual conflict with members of the Apache tribes. The majority of the Column was discharged in August of 1864.