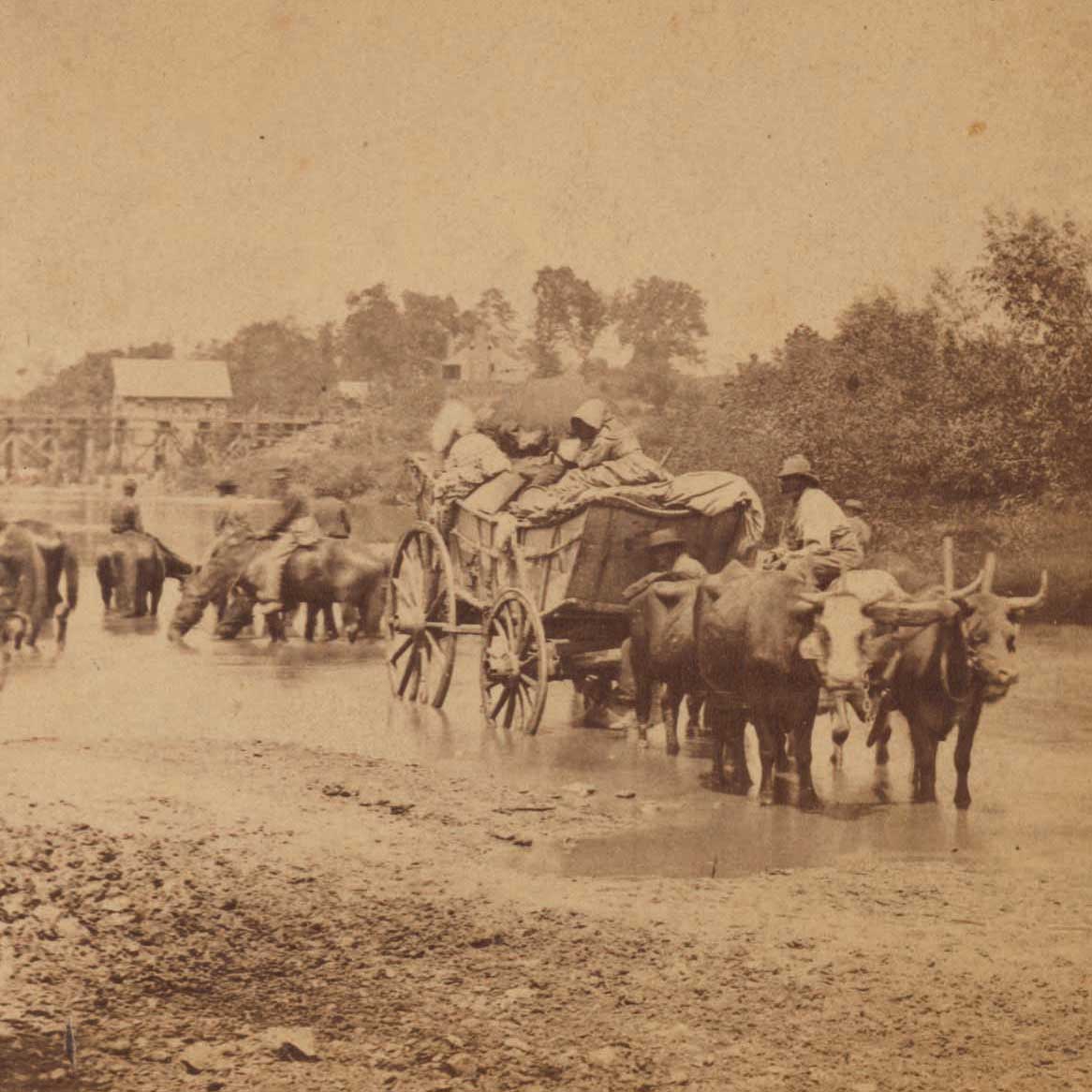

A detail from Timothy H. O'Sullivan's 'Fugitive Negroes, fording Rappahannock'

August 19, 1862, was a hot, frenetic day. More than 55,000 men within John Pope’s Army of Virginia were in full retreat after a string of summer losses and a crushing defeat at the Second Battle of Manassas. Falling back from the Rapidan River through Culpeper County, so many bodies were attempting to flee north that a human traffic jam formed as lines of Union soldiers waited through the night to cross the Rappahannock River.

Among the mass exodus were formerly enslaved men and women, boys and girls, walking and riding on wagons, horses or oxen. For many of these individuals, the retreat of the Union Army that summer was seemingly their last bid for freedom, and they attached themselves to the men clad in blue, heading north.

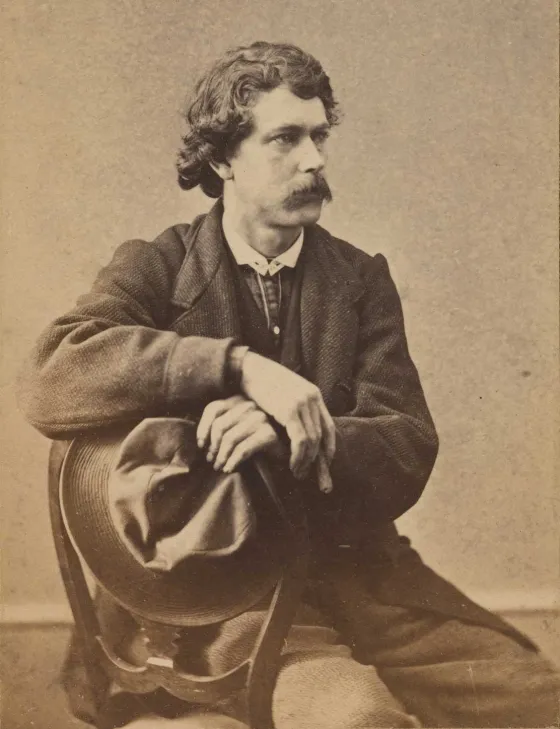

Photographed by Timothy H. O'Sullivan, August 1862

This frantic retreat was famously captured by Irish-born photographer Timothy O’Sullivan, who cut his teeth working with Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner. From a series of at least seven photographs taken on that day, one image, captioned “Fugitive Negroes, fording Rappahannock” has become one of the most frequently reproduced Civil War photographs.

In it, five African Americans traverse the ankle-deep water. Two women sit atop a wagon pulled by oxen, while two men guide the oxen. A young, barefoot Black boy rides bareback next to the wagon, wearing what appears to be a military jacket. Several Union soldiers look on, while several more appear disinterested in the scene. The picture was snapped a few hundred yards downstream from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad bridge, at a narrow crossing inelegantly named Cow’s Ford.

The crossing itself is not unique — albeit it was for those families — but the series of photographs taken by O’Sullivan is. The war correspondent’s photographs represent the only known images of enslaved peoples escaping to freedom. Taken less than a month before the deadly Battle of Antietam and four months before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the crossing at Cow’s Ford captures what Lincoln’s words on paper could not — the physical act of enslaved people liberating themselves.

“It was a scene repeated thousands of times that summer,” writes historian John Hennessy. “[S]laves on a profound but uncertain journey into freedom, into a world that, in 1862, was hardly prepared to receive them.… The scene captures not the posed and tidied up aftermath of emancipation, but rather freedom in progress, unpolished, uncertain.”

Related Battles

14,462

7,387