Exploration and Colonization of the North America

In 1493, an explorer in Spanish service named Christopher Columbus changed the course of world history when he unexpectedly discovered two entirely new continents during an expedition to reach Asia by sailing West from Europe. Over the following decades, Spanish and Portuguese discoveries in Central and South America astounded residents of the Old World. New foodstuffs like tomatoes, chili peppers, chocolate, and corn brought from the Americas radically altered cuisines around the globe. The gold, silver and other precious metals looted from the civilizations encountered there transformed Spain, only recently united through the marriage of Isabelle of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, into one of the wealthiest kingdoms in Europe, fueling the Habsburg Dynasty’s increasingly lavish court life as well as their political and military ambitions. The desire to check Habsburg power and increase their own prestige in the process, therefore, became a prime motivation for Spain’s rivals to begin colonization efforts of their own in the New World, and while these rival powers grabbed whatever bits of the Caribbean and South America they could manage, much of their focus lay in exploring and settling the relatively unknown lands of North America.

Naturally, however, the first European explorers of the northern continent were still the Spanish, and while much of the lands they claimed remained unsettled for centuries, the writ of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (which also included Mexico and the Philippines) extended throughout much of the southern half of the modern United States, from Florida to the Pacific Coast. These early Spanish explorers, called conquistadors, privately financed their expeditions after acquiring royal authorization, and their objectives were much the same as their counterparts in Mesoamerica and Peru: finding gold to loot, souls to convert, and “devil-worshippers” to kill if they refused to do so. Their identities and outlook on the world was essentially medieval, based on religious and martial traditions developed over the years back home during the Reconquista, or effort to drive the Muslim Moors from the Iberian Peninsula, such as the hidalgo (meaning “Somebody”), the ideal landless aristocrat, which many of these explorers were, who comes into prosperity with plunder taken through force of arms against the infidels. According to historian Charles Hudson in his book Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun, these conquistadors “never doubted their own superiority over the native peoples they encountered in the New World. They saw themselves as specially favored people who were carrying out a divine mission,” and this attitude certainly affected Spanish behavior towards the “Indians.” Prominent conquistadors who launched expeditions into North America include Juan Ponce de Leon, the governor of Puerto Rico who gave the name La Florida to the peninsula that bears it today, Hernando de Soto, the first European to document and cross the Mississippi River before dying along its banks in 1541, and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, one of the few survivors of a failed expedition, who wandered for eight years throughout the Southwestern United States before finally returning to Mexico City in 1536. He later chronicled his travels and the various peoples he encountered with a surprising amount of scholarly objectivity, and he is often referred to as one of the first modern anthropologists.

Private military expeditions were not the only tool of the Spanish colonial project, however. As one might expect from a society that so intensely identified with the Catholic Church, missionary efforts played an enormous role in the spread of Christianity throughout Latin America. Their methods varied wildly by monastic or priestly order, but in general, these new missions consisted of semi-autonomous communities centered around a town built along European models run by the clergy who provided religious education, often in local languages, in exchange for manual labor. Defenders of this system claimed that it was an effective barrier against indigenous exploitation, and many missions did clash with the colonial government over such issues, but it was certainly not free from abuse, and could often lead to rebellion if the clergy treated their charges too harshly or went too far in suppressing native cultural practices. Such was the case during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt that took place in modern-day New Mexico, where an alliance of Pueblo tribes rose up against the abuses of the missionaries and drove off more than 2,000 Spanish settlers from their homeland for more than a decade. Many mission communities survived, however, and today cities such as Pensacola, San Antonio and San Francisco all have their roots as either missionaries or Spanish military garrisons.

Though the Kingdom of France shared Spain’s Catholic faith, dynastic politics and constant military clashes over Italy had left them fierce rivals, and so King Francis I did not wait long to commission his own expeditions to North America after Spanish conquests on the mainland. Conflicts between both hostile natives and Spanish colonists prevented French adventurers from setting up permanent settlements throughout the 16th century, however, until Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec in 1608 and claimed the surrounding area. Decades later, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle explored the Mississippi River Delta, claiming the entire river valley for France and naming it Louisiana after Louis XIV. In spite of the huge amount of territory claimed, settlement in French North America remained sparsely populated, requiring the support of allied Natives for both defense as well as securing sources for the fur trade and other commodities, for which they competed fiercely with both Europeans as well as the powerful Iroquois Confederacy the course of the 17th century during the so-called Beaver Wars. To maintain ties with their allies, as they lacked the capacity to subjugate them as the Spanish could in Latin America, the French also authorized missionary activities, typically Jesuit priests, to convert Indians to Catholicism. These priests faced strong competition with native religious traditions and were often blamed for misfortunes, particularly the European diseases that continued to ravage native communities, and so found little success with their official duties, but many acted effectively as explorers and diplomats. One such man, Father Jacques Marquette, was one of the first Europeans to travel through modern-day Illinois and Michigan, for example. Explorers from the Dutch Republic also settled in North America around this time, most famously founding the city of New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island, later New York City, as well as other settlements along the Hudson River Valley. For the Dutch, exploration in the New World coincided with their War of Independence against Habsburg Spain, and so as a relatively new state, colonization initiatives were not just a source of enrichment, but also to mark its legitimacy to imperial rivals. Like the French, the Dutch mainly sought to profit from the fur trade, and though they were far less successful in this regard, their provincial capital of New Amsterdam proved to be far better located geographically than Quebec, giving it better access to markets in across the Caribbean and spurring economic development that continued well after its annexation by England.

Many other European states also attempted to found colonies in the New World during the 17th century, including Sweden in Delaware as well as Russia, which actually arrived in Alaska from the East, but by far the most successful to settle North America proved to be England, another Protestant rival of Spain, which founded colonies across the Atlantic coast. The first successful English expedition to North America, which founded the tiny settlement of Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, originally sought only to find precious metals and other valuable materials that could allow its main patron, the Virginia Company of London, to make a return on their investment. As such, many of the colonists consisted mostly of gentry and artisans with very few experienced farmers, and there were no women amongst them until the next year. Furthermore, relations with the neighboring Powhatan Confederacy were icy at the best of times, and the location the settlers had chosen for their new home was swampy and mosquito-ridden, making agriculture even more difficult and disease a constant threat. These combined factors did make a recipe for success, and for their first few years the settlers faced one unmitigated disaster after another. Fortunes finally turned around when settler John Rolfe convinced his fellow colonists to switch emphasis from exporting precious metals to cash crops, starting with tobacco in 1613. This success in Virginia was soon repeated by future colonies in the Chesapeake and southern Atlantic Coast but also brought the first African slaves to British North America in 1619. Far to the north, however, English colonies took on a rather different character. Starting with the famous landing of the Mayflower at Plymouth Rock, the colonies of New England characterized themselves not economic ventures but places of refuge, specifically for Separatists and Puritan dissenters who believed that the Church of England had not gone far enough in upholding the ideals of the Protestant Reformation, and so left Europe to create their vision of an ideal Christian community in the New World, formally organized as the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629. As in Jamestown, the early settlers in New England faced a myriad of challenges, with many dying off in the first few years and others later deciding that living amidst what they saw as a “savage wilderness” was simply too much of a struggle and to return home, but those who remained continued to persevere and grow and attract further immigrants from Europe, though the colony continued to struggle with civil and external instability. As in Virginia, New England settlers did not seek close connections with surrounding Native American groups. Though they adopted many of their survival techniques, Massachusetts residents made very little official overtures to their indigenous neighbors, believing that their constant displays of English civility and Christian virtue, “A City Upon a Hill” as colony founder John Winthrop put it, could naturally win them over in contrast to Spanish tyranny. This failed to materialize, however, and tensions between natives and colonists remained high before exploding into armed conflicts, such as during King Philips’ War of 1675. The colony’s theocratic government also caused a great deal of internal strife over ideas of religious liberty, as dissenters from the official Puritan theology could face exile, which sometimes led to the founding of several neighboring colonies, or even death, culminating in the infamous Witch Trials of 1692.

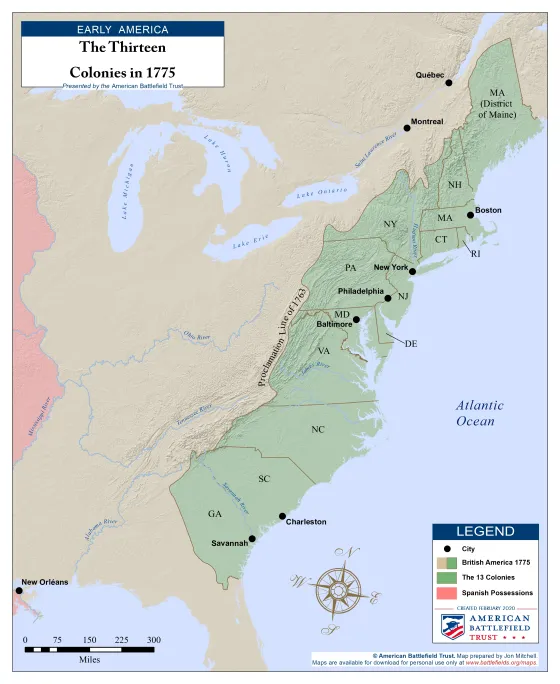

Towards the end of the 17th century, there was little doubt in regards to Britain’s success in colonizing North America. Though they started much later than their imperial rivals and had claimed far less territory than either Spain or France, the settlements they did create were far more developed and populous than their neighbors, giving Britain a distinct edge in any future struggles over control of the new continent

Further Reading

- Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South’s Ancient Chiefdoms By: Charles Hudson

- Gateways to Empire: Quebec and New Amsterdam to 1664 By: Daniel J. Weeks

- The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity By: Jill Lepore.