The Fall of the Rebel Cavalier

Confederate cavalry commander James Ewell Brown Stuart was more quiet and somber than usual on the morning of May 11, 1864, as he rode rapidly towards the dilapidated, abandoned inn called Yellow Tavern.

The day before, he had stopped by the home of Colonel Fontaine near Beaver Dam Station to briefly visit his family. With only minutes to spare, he kissed his wife and young children farewell, then raced back to his command to continue the march to Yellow Tavern. Time was of the essence in the effort to shield the Confederate capital from the threat of General Philip Sheridan's Union cavalry force.

Perhaps Stuart's change of mood was due to his mourning the loss of his close friend Stonewall Jackson, who had died exactly one year before, after Lee's great victory at Chancellorsville. According to an aide that accompanied him to Yellow Tavern, Stuart perceived that "the shadow of the near future was already upon him."

The Overland Campaign commenced in early May, 1864. Unlike previous Union commanders, who proudly proclaimed “Richmond or Bust,” Ulysses S. Grant's first priority was to defeat Robert E. Lee and his army. Only then, Grant believed, would the Confederacy be truly defeated.

When Grant moved east, he brought with him Major General Philip Sheridan, a hot-tempered and tenacious man, to take command of the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. However, not long after the start of the campaign, a fight erupted between Sheridan and General George Meade, the overall commander of the Army of the Potomac. Meade was just as hot-tempered as the fiery cavalry commander.

In the opening days of the campaign, Union cavalry had not been effective in reconnoitering, screening, and clearing roads of Confederate forces for the advance of the Union infantry. Meade criticized Sheridan for laxity in executing his orders. Sheridan blamed Meade for meddlesome interference in the affairs of the cavalry. During a heated argument, Sheridan maintained that he "could whip Stuart" if Meade would only let him. When Meade complained to Grant about the stubborn cavalry officer and his audacious claim, Grant surprised Meade by saying, "Let him go out and do it."

Sheridan left that night with more than 12,000 cavalrymen behind him. The thirteen-mile-long column made slow progress. They stopped at Beaver Dam Station, the Confederate supply depot along the Virginia Central Railroad, where they destroyed railway cars, two locomotives, ten miles of railroad track and telegraph wires, and saved around 400 captured Union soldiers on their way to Confederate prison camps.

Stuart was certain that Sheridan was heading towards Richmond. The blue troopers continued to move slowly, taking their time, while Stuart hurried his men to Yellow Tavern. The tavern stood at the convergence of the Mountain and Telegraph Roads as they wound towards the capital—Sheridan’s men were certain to pass through the area. However, in the words of the historian Shelby Foote, Sheridan in fact "wanted Jeb to win the race, since only in that way would it end in the confrontation he was seeking."

Stuart indeed won the race to Yellow Tavern, arriving several hours before Sheridan with 5,000 Confederate cavalrymen, less than half the number of Sheridan's command. Sheridan's men were also armed with rapid-fire carbines and were well-rested, while Stuart's cavalry carried single-shot muzzle loaders and were exhausted from the rapidity of the march.

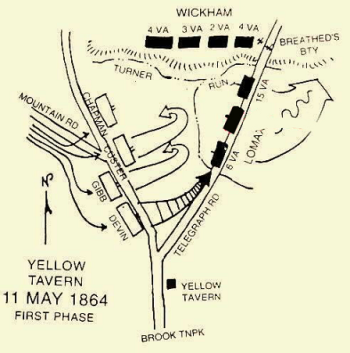

Stuart rapidly placed his brigades to meet the enemy. While James B. Gordon's North Carolina cavalry brigade harassed the rear of Sheridan's column, Stuart placed his other two brigades led, by Generals Lunsford Lomax and William C. Wickham of Fitzhugh Lee's division, in an inverted V formation a mile north of Yellow Tavern. Lomax's brigade composed the left arm and Wickham's brigade the right arm.

Late in the morning of May 11, the first shots of the battle of Yellow Tavern were fired as Sheridan's men encountered Confederate pickets on the Mountain Road. The Union troopers quickly sprang into action.

Sheridan dispatched a brigade to block Gordon's attack on his rear, driving him off after an hour-long hand-to-hand struggle. At the same time, he sent the divisions under Brigadier Generals James H. Wilson and Wesley Merritt to attack Wickham and Lomax respectively.

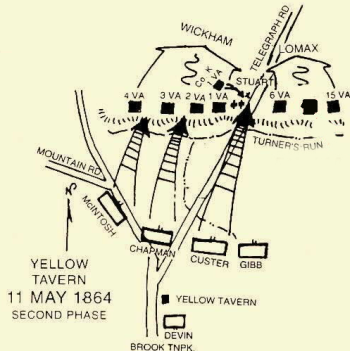

Although Stuart's horse artillery tore holes in the Union ranks, Wilson and Merritt used their superior numbers to push the Confederates back until Sheridan's troops were able to occupy a section of the turnpike. In order to maintain the pressure on the Confederates, Sheridan sent in dismounted troops of the 5th and 6th Michigan, followed by the mounted regiments of the 1st and 7th Michigan under Brigadier General George Custer, to pummel the Confederate left flank.

Lomax's line began to collapse towards Wickham, and Jeb Stuart, attempting to rally his men at "the point where the greatest danger threatened," unloaded his pistol at the Michiganders as they charged past him.

However, the 1st Virginia Cavalry, which had fought with Stuart since the beginning of the war, burst onto the scene and hurled the Yankees back with a thundering counter-charge.

As the Michigan regiments retreated, a dismounted trooper spotted Stuart. Despite the confusion of the withdrawal, the Wolverine took careful aim with his revolver and squeezed off a round. Both the commander of the 5th Michigan, Col. Russell Alger, as well as Custer, wrote Pvt. John Huff, a member of Alger's regiment, fired the fatal shot. Despite these claims, there is no other evidence that points to Huff as the individual who mortally wounded Stuart, and the soldier's true identity remains a mystery.

JEB Stuart lurched forward in his saddle, his black plumed hat dropping to the ground. Seeing the blood on his general's coat, Captain Gustavus Dorsey, one of Stuart's closest staff members, extended his arm towards Stuart, asking desperately if the general was shot. "I'm afraid I am," Stuart said as he was carefully removed from his horse and rested against a nearby tree.

Stuart insisted that Dorsey return to his men and "drive back the enemy," believing that since he was wounded he "could be of no more service." Dorsey remarked, "I cannot obey that order," and instead remained by Stuart's side until the injured general could be moved to safety.

Soon, an ambulance was secured and the general was lifted into it. As soon as the ambulance began to move off the field, the Confederate line broke. Seeing his men stream by his ambulance in panic, Stuart, in much pain and dismay, shouted out at them, "Go back! Go back, and do your duty, as I have done mine, and our country will be safe. Go back! Go back!" and then after a pause yelled, "I'd rather die than be whipped!"

The ambulance ride was sluggish and painful as it jolted along to Richmond, taking a longer, more roundabout path to avoid Sheridan's cavalry. A doctor and one of Stuart's aides, Lieutenant Walter Hullihen, shifted Stuart onto his side to examine the wound. Huff's bullet had pierced through Stuart's right abdomen, tearing through blood vessels and puncturing his intestines.

Addressing Hullihen by his nickname, Stuart asked, "Honey-bun, how do I look in the face?" Hullihen, in an attempt to reassure the general and himself, replied, "You are looking right well. You will be all right." Although very pale and weak from the loss of blood, Stuart remarked, "Well, I don't know how this will turn out; but if it is God's will that I shall die I am ready."

By May 12, Stuart reached Richmond and was settled at his brother-in-law's house. However, his mind was still on the fighting. From his bed he listened to the din of battle, as Fitzhugh Lee, now in command of Stuart's cavalry, kept up the attack on Sheridan's troops, who were now attempting to cross the James River. In the end, Sheridan chose not to strike Richmond and instead moved his troops southeast to join Major General Benjamin Butler's Army of the James at Bermuda Hundred before returning to the Army of the Potomac.

"General, how do you feel?" asked President Jefferson Davis, who was disheartened to see the lively cavalryman on his deathbed. "Easy, but willing to die, if God and my country think I have fulfilled my destiny and done my duty," Stuart replied.

Late in the afternoon of May 12, Stuart asked the doctor if he would be able to live through the night. The doctor told him that "death was close at hand." He did not expect Stuart to survive the night. "I am resigned if it be God's will" Stuart answered, "but I would like to see my wife. But God's will be done." His last words were spoken around 7 o'clock the night of May 12: "I am going fast now; I am resigned; God's will be done." He was 31 years old.

Flora Cooke Stuart, the general's wife, had been delayed by railroad damage inflicted by Sheridan’s troopers. When she arrived at the house in which Stuart was staying, she was told that her husband had died four hours before her arrival.

At Yellow Tavern, Philip Sheridan proved himself to be a capable cavalry leader and had eliminated Lee's most valuable and skilled cavalry officer. When General Lee received the news of the death of Jeb Stuart, his good friend and most trusted cavalry commander, he sorrowfully noted, "Stuart had never brought me a piece of false information,” and that “I can hardly think of him without weeping." JEB Stuart's actions and sacrifice and Robert E. Lee's words of admiration solidified his place in history as one of America’s best cavalry officers.