By Parker Hills

To keep Nathan Bedford Forrest occupied during his advance on Atlanta and away from his lines of communications, William T. Sherman ordered Union General Samuel Sturgis to move into Mississippi. Forrest pursued Sturgis, and on a hot June day, the two forces clashed at the small northeastern Mississippi junction of Brice's Crossroads.

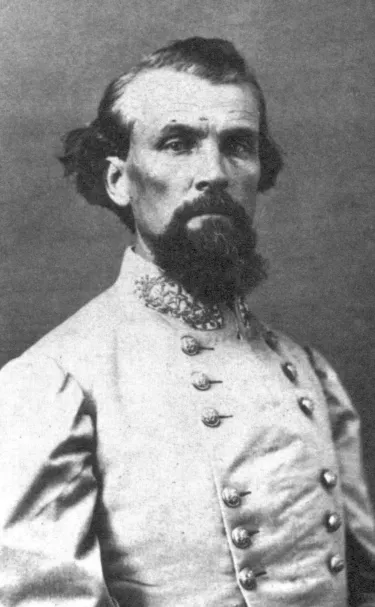

THE MISSISSIPPI SUN LURKED behind a mask of emptied rain clouds in the early morning of June 10, 1864, and then temperamentally burned its gray-white shroud away. Now the sun blazed away like a white-hot disc, seeming stationary in the sky. Desperate soldiers and exhausted dray animals sweated, struggled and suffered in the knee-high cornfields and the chafing brush of the scrub-oak woods, With agonizing deliberation the sun crept across the heavens, and almost every living creature on the battlefield eagerly anticipated day's end — almost. With eves blazing and temper raging, Confederate Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest was too busy making history, and the demise of the sunlight meant less light for him to destroy his enemy.

The enemy that day was Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis, a 41-year-old West Pointer from Pennsylvania, who commanded a formidable force of 8,500 Union infantry and cavalry. Sturgis's hounds were pursuing the fox Forrest for the second time. The first raid was aborted in early May after an unsuccessful hunt from Memphis, Tenn., to Ripley, Miss. Forrest was still loose, marauding Union lines of communication seemingly at will, and enraging Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman.

"Cump" Sherman had felt the sting of Forrest in February, when "that devil" routed the reinforcing cavalry arm of the Meridian Expedition in a series of running gunfights from southeast of West Point, through Okolona, to just below Pontotoc, Miss. Now Sherman planned an advance into Georgia, pursuing Gen. Joe Johnston's army while Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant was besieging Gen. Lee's army at Petersburg, Va, An effective Forrest raid on a vulnerable Union supply line could end any Union advance to Atlanta, and Sherman would have none of that Thus, Sturgis became Sherman's bait for a diversion.

Forrest realized the significance of Sherman's campaign into Georgia, and appealed to his superior, Lt. Gem Stephen Lee, for approval of a cavalry raid into middle Tennessee and Kentucky to chop Sherman's lines of communication. "The time has arrived, and if I can be spared and allowed 2,000 picked men from Buford's division and a batten- of artillery, will attempt to cut the enemy's communication in middle Tennessee." Lee approved, and Forrest moved out.

Forrest had hardly ridden northward when, on June 3, Lee received news of a large expedition heading into Mississippi from Memphis. Sherman had baited the hook, and Lee took the bait by diverting Forrest back into Mississippi to repel Sturgis's invasion.

Sturgis had marched out of Memphis and Lafayette, Tenn., with a force double that of Forrest. The Union column boasted 4,800 infantry, 3,300 cavalry, 400 artillerymen with 22 guns and a supply train of 250 loaded wagons. The troops had been selected because of their combat experience, and many of the cavalrymen were armed with the newest Colt repeating rifles as well as breech loading carbines.

Among them was Col. Edward Bouton, a 30-year-old native of New York and businessman of Chicago, who had sold his business and spent his personal funds to raise and equip an artillery battery. Bouton's battery fought well at Shiloh, and he was selected to command a regiment of United States Colored Troops. He now commanded a brigade of two regiments totaling 1,200 soldiers with two pieces of artillery.

Sturgis's divisions moved into Mississippi with the mission of bagging Forrest, and, as further enticement to draw Forrest in, the destruction of Mississippi's fertile Black Belt and the vital Mobile and Ohio Railroad in the vicinity of Tupelo. Forrest's new mission was to prevent Sturgis from accomplishing either objective.

On June 6, elements of Brig. Gen. Ben Grierson's cavalry under Col. Joseph Karge destroyed several miles of railroad at Rienzi. On June 7, portions of Forrest's and Grierson's cavalry skirmished briefly at Ripley. On June 9, Sturgis's entire command had inched past Ripley on the Ripley-Guntown road to a farm owned by the Stubbs family, nine miles northwest of a hamlet called Brice's Crossroads. The Ripley- Guntown road ran through Brice's to Guntown, and was cut along its narrow and winding path by four miry streams. Forrest had bet that the Union Army would march due east along the Ripley-Rienzi road, since it was in better condition and had been used by Grierson's cavalry days before. Grierson, however, had reported to Sturgis that it was lacking in fodder and forage. Sturgis changed his order of march toward Guntown in search of better terrain. Forrest had shifted his forces northward toward Rienzi.

The bulk of Forrest's command, Bell's Fourth Brigade of Buford's Second Cavalry Division, was at Rienzi, 25 miles north of Brice's Crossroads on June 9. The 2,787 Confederates were commanded by Col. Tree Bell, a 48-year old Tennessee plantation owner. Bell's superior was Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford, a 44-year-old Kentucky horse farmer and West Point graduate.

Seven miles south of Rienzi, and 18 miles from the Crossroads on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad, stood the town of Booneville. On June 9, Booneville was the campground of Forrest and his escort of 135 Tennessee and Georgia troopers. Also there were two brigades of cavalry and half of the corps artillery under Capt. John Morton. The artillery consisted of two batteries, Morton's and Rice's, with four guns each.

Col. Hylan Lyon, a 28-year-old Kentuckian and West Pointer, commanded the Third Cavalry Brigade of 800 at Booneville. Lyon had resigned his commission in the U. S. Regulars to go with the Confederacy, only to be captured with his command at Fort Donelson. After seven months as a prisoner on Johnson's Island, Ohio, he was exchanged at Vicksburg, and saw action on the periphery Of the Vicksburg Campaign.

Col. Edmund Rucker, also at Booneville, was attached to Buford's Division from Chalmers's Division, and commanded 700 horsemen. The 28-year-old was a self-educated Tennessean who enlisted as an infantry private, became an artillery captain, and, as a lieutenant colonel, had fought beside Forrest at Chickamauga.

South of Booneville and six miles due east of Brice's Crossroads was the 500-man brigade of Brig. Gen. Roddey's independent division, commanded by Col. William Johnson, an Alabama man with considerable cavalry experience. In fact, Johnson's troopers would ride into Baldwyn from Alabama late the night of June 9, just in time to assist Forrest in the upcoming battle.

Early on the night on June 9, Forrest met in Booneville with his commander, 30-year-old Lt. Gen. Stephen Lee. Lee ordered Forrest to fall back southward to the town of Okolona on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. Here Forrest was to unite Buford's Second Division with Chalmers's First Division, thus concentrating Forrest's Cavalry Corps for battle with Sturgis's army. After the meeting, Lee boarded a train for Okolona, but left Forrest with the authority to act against the enemy if the situation warranted.

Late June 9, Forrest called a council of his officers to discuss the latest scouting reports. He learned Sturgis's entire command was at Stubbs Farm, en route to Guntown via Brice's Crossroads, and decided to strike. He planned to reach the high ground over Tishomingo Creek at the Crossroads first, catching Sturgis's men as they trudged upward from the bottom. Forrest ordered his officers to move out at 4 a.m.

While Forrest's men were riding in the pre-dawn hours of June 10, Sturgis was in no hurry to break camp, and Grierson's 3,300 cavalrymen didn't ride until 5:30 a.m. Col. William McMillan's 5,200 infantrymen cooked a leisurely breakfast, and didn't move down the Ripley road until 7 a.m. Despite the Federal tardiness, the Union cavalry had a much shorter route to Brice's, and arrived at the Crossroads first. Forrest would have to improvise when he arrived.

Forrest had known through his scouts that the Yankee cavalry would be approximately three hours in advance of the infantry; thus the Union force would be divided. His battle plan, therefore, was to defeat the forces separately: first the cavalry, then the infantry.

When Grierson's two brigades of bluecoats passed through Brice's Crossroads and ran into Lyon's Confederate advance, the Yanks dismounted and deployed into line of battle on the edge of Porter's Field about one mile east of charge, and we will give them hell." He rode down to the Guntown road and ordered Capt. H. A. Tyler's squadron of Kentuckians, his escort, and Capt. Henry Gartrell's Georgians to ride around the Union right to the enemy rear. The plan was to keep the Yankees pinned in by a vigorous attack all along the front, and surprise them with a strike on both flanks.

After two or three cannon blasts, the bugle sounded, and the Confederate line sprang forward with six-shooters blazing. Haller and Mayson pressed their four guns forward, each barrel spouting forth 54 death-dealing, 1-1/2" iron balls at point-blank range.

The Union forces were driven back toward the Brice house, and the converging Confederate fires massed at the Crossroads. The confused Federals began to panic and many took refuge in the house and behind the tombstones of the Bethany Cemetery. Most scrambled down the ridgeline toward the Tishomingo Creek bridge. As the Confederates emerged from the woods, six Union guns were captured and several were turned upon the fleeing Yanks. Brown's section, which had fallen behind to fill the ammunition chests, dashed forward. Sgt. C. T Brady glimpsed a 3" steel rifle among the captured guns and ordered his iron smoothbore unlimbered. He limbered up the rifle and took it into action. Lt Brigg's six-pounders came up to the Crossroads, and all guns "poured a torrent of shell and double-shotted canister upon the fleeing enemy as they huddled infantry, cavalry; wagons, and ambulances in an almost inextricable coil in the valley approaching Tishomingo Creek."

Lt. Brown pressed his section down the Ripley road, 100 yards toward Tishomingo Creek. He soon silenced the Federal guns on the hill, and the position was captured with many prisoners and three pieces of artillery. The sections of Haller and Mayson galloped forward to establish a position on the hill. They blasted with double-shotted canister at the fleeing enemy on Tishomingo Creek, barely 200 yards away.

Several wagons blocked the bridge: one overturned, and some had their teams killed. Morton said the Yanks "rushed wildly into the creek, and as they emerged from the water on the opposite bank in an open field, our artillery played upon them for a half a mile, killing and disabling large numbers."

Forrest's pursuing troopers soon cleared the bridge by throwing the wagons into the stream, and a section from each battery was worked across and supported by Forrest's escort. They blasted away at Sturgis's reserve brigade of USCTs, which was valiantly covering the retreat. The four cannon drove the Federal blocking force from the ridge back of Holland's house and sent them scampering across Dry Creek. The narrow road with dense woods on each side made it impossible for Capt. Morton to use more than four guns at once "but that number was kept close upon the heels of the retreating enemy, and a murderous fire prevented them from forming to make a stand." The Yanks attempted to form a defensive line on the prominent ridge extending southward from the Hadden house, but Morton's redlegs placed a few well-directed shots into the Union lines. The Confederate cavalry then charged across Dry Creek, driving back the bluecoats.

As the Federals retreated from the Hadden house ridge line, Morton galloped a section of each battery to the ridge and fired several rounds into the fleeing soldiers. The Yanks ran through the open fields on both sides of Philips Branch, and set up another defensive line behind a fence in the woods just west of the creek.

Forrest rode up to Morton's guns on the ridge line, dismounted, and used his field glasses to observe the enemy. Morton's cannoneers began firing shell and solid shot at the Yankees behind the fence line several hundred yards away. "The enemy's shots were coming thick and fast; leaden balls were seen to flatten as they would strike the axles and tires of our gun carriages; trees were barked, and the air was laden with the familiar but unpleasant sound of these death-messengers." Morton turned to Forrest and screamed, "You had better get lower down the hill, General." Expecting the general to chastise him, the captain was surprised when Forrest replied, "Well, John, I will rest a little." He stepped down the hill, out of danger, and sat behind a tree in deep study for a few moments. His rest was interrupted when the head of the cavalry column approached.

As the cavalry rode up, Forrest said to Morton, "Captain, as soon as you hear me open on the right and flank of the enemy over yonder, charge with your artillery down that lane and cross the branch." Rice, who overheard, approached Morton and said, "Be-God, who ever heard of artillery charging?" "You heard the order, Captain Rice," Morton replied, "be ready."

Morton ordered Lts. Brown and Briggs to be ready to gallop forward at a moment's notice.

The Union troops near Philips Branch observed Forrest's flanking movement, and fell back up the hillside to the Agnew house on "White House Ridge." Forrest attacked the retiring Federals. Brown pressed his section down the Ripley road and opened fire. Briggs moved his section forward, and blasted a few shots into the Yankees. Brown's section and a section of Rice's battery were pushed forward across Philips Branch and up the hillside under a sharp fire from the Federals, who had rallied at the Agnew house. Brown's section went into battery on the right of the Ripley road, and Rice's section positioned itself in the road, "just where the road turns before reaching Dr. Agnew's house."

As Morton was about to advance his four guns, he heard the Federal officers, barely 60 yards away, give the command to charge. The Federals from Illinois, Minnesota, and the U. S. Colored Troops surged forward, and the fighting was hand to hand. Morton's cannoneers stood firm and blasted double canister into the blue line. The Confederate cavalry fired volley after volley into the oncoming bluecoats. The Yanks "got almost within handshaking distance of our guns," Morton reported. At this critical moment, Col. Lyon's men arrived and formed on Morton's right, springing forward with loud cheers. Sturgis's men were beaten back.

The sun was setting, and rain would soon fall. But Forrest pursued the retreating Federals five or six miles until it was too dark to continue. He allowed his men a brief rest while he took a 10-man detachment to trail the foe. At 1 a.m. on the 11th, Forrest continued to pursue Sturgis, driving the terrified Yankees through Ripley. Forrest hammered away at the Union rear and flanks for 55 miles, stopping late that night near Salem, just outside the modern town of Ashland.

Forrest captured 16 cannon, 1,500 stands of small arms, 300,000 rounds of small arm ammunition, 16 ambulances, 176 wagons, 161 mules, 23 horses, and all of the Federals' baggage and supplies. The Federal casualties included 223 killed, 394 wounded, and 1,623 missing, for a total of 2,240. The Confederates lost 96 killed and 396 wounded, for a total of 492.

On the morning of June 12, Forrest recalled his men from the pursuit and, passing the artillery on the return to the battlefield, he said to Morton, "Well, John, your artillery won this fight." "General, you pressed us up pretty close at times," Morton responded. "Yes, artillery is made to be captured," Forrest calmly replied, "and I wanted to see if they could take yours."

Parker Hills, Mississippi's counter-drug coordinator, served in the U.S. Army, 1969-1976, and now is a colonel in the Mississippi Army National Guard.

Related Battles

2,610

495