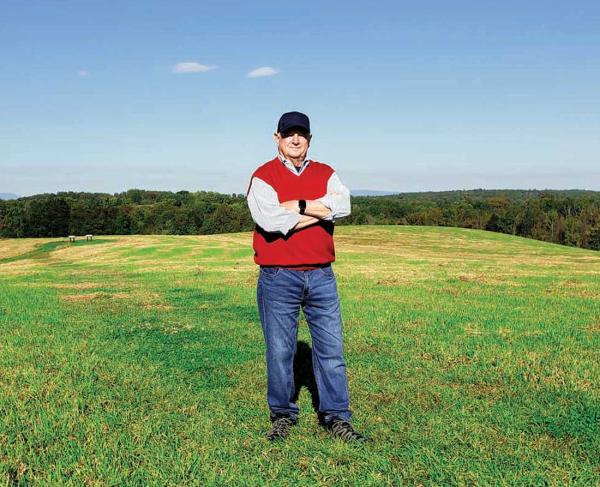

Fighting for Fleetwood Hill

Historian Eric Wittenberg discusses the intense combat on Fleetwood Hill, the heart of the Brandy Station battlefield and the scene of the most intense mounted fighting of the Civil War.

There is not any piece of real estate found anywhere on the North American continent that has witnessed more combat than the southern terminus of Fleetwood Hill, Culpeper County, Virginia.

It is a fact that Union and Confederate cavalry fought four major engagements on Fleetwood; John Singleton Mosby's raiders struck Union rearguard troops at the summit’s base and numerous commanders established headquarters lodgments on Fleetwood, including Confederate cavalry chief, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac, affixed his sprawling headquarters on a spur of Fleetwood during the army’s winter encampment over the winter of 1863-1864.

Although four engagements were fought atop Fleetwood, none of course is more famous than the June 9, 1863 Battle of Brandy Station. Stuart had his headquarters on the southern terminus of Fleetwood Hill, and the crest became the site of the heaviest fighting of the day. For that reason alone, Fleetwood is worthy of preservation.

The Union Cavalry Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, crossed the Rappahannock River at two locations on the morning of June 9. The right wing, commanded by Brig. Gen. John Buford, crossed at Beverly’s Ford, and the left wing, commanded by Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg, crossed six miles downriver at Kelly’s Ford. Buford’s command, consisting of his 1st Cavalry Division, three horse artillery batteries, and a brigade of hand-picked infantry, advanced toward Brandy Station while Gregg's 3rd Cavalry Division thrust toward Brandy, a way station on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad situated near the base of Fleetwood Hill. Col. Alfred N. Duffíe's 2nd Cavalry Division advanced toward Stevensburg, with the mission of protecting Gregg's left flank. A second select brigade of Union infantry guarded Kelly’s Ford Road and the critical crossing back at Kelly’s Ford, itself. The combined Union cavalry forces would fall upon and disperse a large concentration of Confederate cavalry that Pleasonton believed would be ensconced in and around Culpeper.

It was a brilliant plan, but for one major flaw: it was based on a faulty premise. Pleasonton did not know that the Confederate cavalry was in fact camped just across the Rappahannock and that most of it occupied the fields between the river and Fleetwood Hill. Hence, when Buford’s troopers splashed across the Rappahannock at Beverly's Ford, they immediately met stout resistance from Confederate cavalry, and Buford's once-promising advance bogged down for most of the morning in the woods just beyond St. James Church on Beverly's Ford Road.

Gregg's command was supposed to cross simultaneously with Buford's but the leading element of his column (Duffie's Division) got lost and was significantly delayed. As a result, Gregg's troopers did not complete their advance on Brandy Station until nearly 10:30 that morning.

Stuart's personal tent-fly, now empty, fluttered above Fleetwood Hill as Gregg's Division trotted toward the crest, a half-mile distant. Other than a few staff officers and orderlies, Fleetwood Hill was nearly devoid of Confederate presence as Stuart departed for St. James church to mange the fighting at that point. . However, a twelve-pound Napoleon of Capt. Roger P. Chew's Battery, commanded by Lt. John W. "Tuck" Carter, happened to be present, serendipitously.

Maj. Henry B. McClellan, Stuart's able adjutant, was the highest-ranking officer on the summit, and McClellan finally spotted the head of Gregg's column advancing toward Fleetwood Hill. Quickly grasping the urgency of the situation, he frantically dispatched a series of orderlies to warn Stuart at St. James that his headquarters was soon to be attacked. Realizing that if he did not take charge, nobody would, the major sprang into action. McClellan ordered Carter to lob a few shells at the Yankee cavalry, which caused the leading brigade to halt in some confusion. This brief delay by the Federals was a good thing, because at that point, Carter's gun crew, a few orderlies, and Major McClellan remained the only Confederate force holding Fleetwood Hill.

McClellan's couriers found Stuart directing the fighting against John Buford's attacking squadrons. Stuart did not at first believe Yankees were in force in his rear until McClellan's second courier arrived. The repeated urgency of McClellan's messages, combined with the sound of Carter's initial cannonading, finally prompted Stuart to pull two regiments, the 12th Virginia Cavalry and the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry of Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones' Brigade, from Buford's front and send them racing back to Fleetwood. The 12th Virginia arrived just as Carter ran out of ammunition and was retiring his gun. The surging Federals were only fifty yards from the crest of Fleetwood Hill when the Virginians arrived.

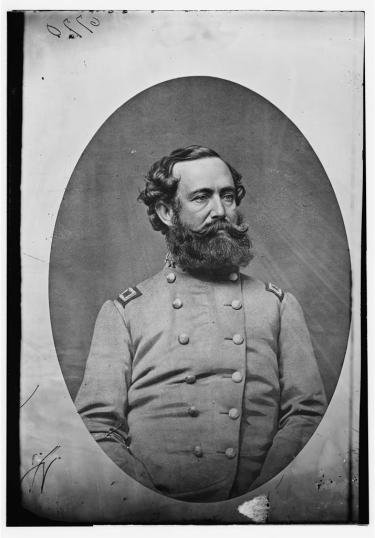

Stuart, now fully aware of the terrible crisis he faced, ordered immediate support from Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton's brigade, still back at St. James. With Cobb's Legion in the lead, Hampton and his brigade galloped across country and headed straight for Fleetwood and the oncoming Union troopers of Col. Sir Percy Wyndham's brigade, which led Gregg's advance.

The veterans of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry led Wyndham's advance. "With a ringing cheer," the 1st New Jersey, with Lt. Col. Virgil Broderick at their head, "rode up the gentle ascent that led to Stuart's headquarters, the men gripping hard their sabers, and the horses taking ravines and ditches in their stride." The Jerseymen briefly took possession of the hill, but the Confederate onslaught crashed into them, driving them back. "The two forces met with a crash that could have been heard miles away," recalled a Confederate horse artillerist. "Back and forth they swayed across the slope of Fleetwood Hill."

It took a few precious minutes for Hampton's reinforcements to reach the hill. As the head of the Confederate column reached Fleetwood, it met Carter's withdrawing gun, now entirely out of ammunition. "No more brilliant spectacle was ever witnessed than the brave Hampton leading on his gallant Carolinians, as with flashing sabers they plunged into the masses of Gregg's troopers and scattered them far and wide," recorded one of Stuart's staff officers. As Capt. William W. Blackford, of Stuart's staff, recorded, "There now followed a passage of arms filled with romantic interest and splendor to a degree unequaled by anything our war produced."

Stuart now ordered the remainder of Jones' Brigade and the balance of Hampton's Brigade and Hart's Battery to Fleetwood, and the Confederate chieftain himself rode to the sound of the fighting, arriving just behind the 12th Virginia, with White’s 35th Battalion close behind. As Southern artillery crested the hill, Captain Hart observed the panoramic drama playing out in front: "As we came near Fleetwood Hill, its summit, as also the whole plateau east of the hill and beyond the railroad, was covered with Federal cavalry." Hart's gunners deployed just north of the Carolina Road and quickly opened fire.

A wild melee broke out. "Round and round it went; we would break their line on one side, and they would break ours on the other," recalled a trooper of the 12th Virginia. "Here it was pell mell, helter skelter—a yankee and there a rebel—killing, wounding, and taking prisoners." Another Virginian observed, "On each side, in front, behind, everywhere on the top of the hill the Yankees closed in upon us. We fought them single-handed, by twos, fours, and by squads, just as the circumstances permitted." Solo combat raged everywhere. The 1st New Jersey repulsed two charges of the Confederate cavalry, and casualties thinned their ranks. They lost all unit cohesion, and were "no longer in line of battle, fighting hand to hand with small parties of the enemy, and with many a wounded horse sinking to the earth." Trying to open a route of retreat, a large portion of the regiment charged Confederate guns that had unlimbered on the crest of Fleetwood, just west of the Carolina Road.

The Jerseymen charged down toward the Carolina Road, hoping to cu their way out. Their commander, Brodrick, and his second in command, Maj. John Shellmire, both fell mortally wounded in the wild melee. At about the same time, Colonel Wyndham, the brigade commander, was badly wounded in the leg. The Jerseymen finally withdrew, with one hundred fifty prisoners in tow. With that, the determined Confederates briefly regained possession of Fleetwood Hill, while the balance of Wyndham’s brigade continued slugging it out with Hampton's troopers.

"The whole plain was covered with men and horses, charging in all directions, closed in hand to hand encounters, with banners flying, sabers glittering, and the fierce flash of firearms, amid the din, dust, and smoke of battle," recalled a member of the 1st North Carolina. "Such scenes cannot last beyond a few fearful minutes. And so here." One of Hampton's Georgians saw "thousands of flashing sabers streamed in the sunlight; the rattle of carbines and pistols mingled with the roar of cannon; armed men wearing the blue and the gray became mixed in promiscuous confusion; the surging ranks swayed up and down the sides of Fleetwood Hill, and dense clouds of smoke and dust rose as a curtain to cover the tumultuous and bloody scene." Soon the whole plain in front of Brandy became a whirling blur of saber swinging duels, with the two sides mixed promiscuously. "The fighting spun out more and more from all sides, moving on the entire periphery of a circle with a diameter of about a thousand paces," recalled a Prussian observer attached to Stuart's headquarters. "It is impossible to present the individual scenes of this twelve hour battle, particularly since a man could see and hear only what was happening right around and before him. Shrapnel, case shot, and pistol balls hissed through the air from all sides. Excited, riderless horses were running about like scalded cats, and Negroes in mortal terror ran from one side to the other with their masters' horses, not finding protection anywhere against enemy shells. Ambulances assembled in the center in a thick mass. Men who were running away toppled over one another without sense or reason. Lost soldiers asked about their regiments, and couriers sought Stuart out to request speedy reinforcement. In short, it was chaos."

While the initial fighting raged, Capt. Joseph Martin’s 6th New York Independent Battery deployed on a small knoll above Flat Run at the base of Fleetwood Hill, where its gunners greatly annoyed enemy cavalry. Finally growing weary of the Yankee artillery, Lt. Col. Elijah V. White, commanding the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, ordered his men to charge the battery, making their way through a perfect storm of shot and shell. They drove off the gunners and captured the guns.

White and a few of the Comanches attempted to turn Martin's guns on the Yankees but received no support, and a Federal counterattack loomed. One of Gregg's staff officers found two companies of the 1st Maryland Cavalry and led them forward in an attempt to rescue the guns. Joined by other nearby Federals, the Marylanders charged down the hill. Witnessing a wall of blue descending on him, White pulled back, leaving the guns for the Yankees—but only briefly. The guns, however, were largely useless. One gun tube had burst, and the other was rendered useless by having a ball rammed down it without powder. In addition, nearly all of the battery’s horses had been killed by enemy fire, meaning that the guns were immobile, a disastrous condition for horse artillery.

Gregg then ordered Col. Judson Kilpatrick to attack with his brigade to the right of Wyndham, and its charge caused a portion of the Confederate force to "break...all to pieces...[it] lost all organization and sought safety in flight." As Kilpatrick's troopers battled up the crest of Fleetwood Hill, things looked momentarily bleak for the Rebel cavalry. Kilpatrick first ordered the 10th New York Cavalry, situated at squadron front near the railroad tracks to lead his attack up the eastern slope of Fleetwood Hill. "The regiment was well in hand, the formation perfect," recalled a New Yorker. "The enemy in small numbers advanced from the hill to oppose us." Putting spurs to their horses, the New Yorkers surged forward up the right side of Fleetwood Hill.

Hampton's brigade arrived in the nick of time. With Wade Hampton leading the charge in person, the gray-clad cavalry pitched head long into the Yankee cavalry on the slope of Fleetwood Hill, and the melee was on. Stuart, following along behind Hampton's column, could be heard to yell, "Give them the sabre, boys!" Sabre charge after sabre charge occurred, with the whirling melee deteriorating into small, isolated fights among pockets of men; all organization disappeared as the horsemen clashed. "What the eye saw as Stuart rapidly fell back from the river and concentrated his cavalry for the defense of Fleetwood Hill, between him and Brandy," recalled a Confederate staff officer, "was a great and imposing spectacle of squadrons charging in every portion of the field—men falling, cut out of the saddle with the sabre, artillery roaring, carbines cracking—a perfect hurly-burly of combat." A brilliant charge by Cobb’s Georgia Legion of Hampton’s brigade "swept the hill clear of the enemy, he being scattered and entirely routed. I do claim that this was the turning-point of the day in this portion of the field, for in less than a minute’s time the battery would have been upon the hill." Making their way through a small orchard atop Fleetwood, the Georgians "mixed with them...each man fencing and fighting for the time with his individual foe." The fierce charge of the Georgians drove the 10th and 2nd New York Cavalry Regiments off the hill in total disarray.

Rallying his troopers, Kilpatrick shouted to his final regiment, the 1st Maine Cavalry, "Men of Maine! You must save the day! Follow me!" As the Maine men galloped hard up Fleetwood, they saw a magnificent sight. "The whole plain was one vast field of intense, earnest action. It was a scene to be witnessed but once in a lifetime, and one well worth the risks of battle to witness," recalled one.

"In one solid mass this splendid regiment circled first to the right, and then moving in a straight line at a run struck the 6th Virginia Cavalry in flank. The shock was terrific! Down went the rebels before this wild rush of maddened horses, men, biting sabres, and whistling balls." Their ferocious charge crashed into the Confederate horsemen. "The two regiments were interwoven,” recalled a captain of the 1st Maine. "It was cut, thrust and fend off; numbers indulged in a personal grapple."

"Here the tide of battle alternated, brilliant charges were being made, routing the enemy and in turn being routed," remembered one of Hampton’s troopers. The Jeff Davis Legion of Hampton's command attacked to the east of the railroad tracks, while the balance of Jones' Brigade charged to the west. They drove the Federals back, "and then, for an hour or more, there was a fierce struggle for the hill, which seemed to have been regarded as the key to the entire situation. This point was taken, and retaken once, and perhaps several times; each side would be in possession for a time, and plant its batteries there, when by a successful charge it would pass into the possession of the other side, and so it continued" until Gregg had no choice but to break off his attack and withdraw.

The defeated Federals melted away, with some of Hampton's troopers in hot pursuit. However, Stuart had ordered two of the South Carolinian's regiments to remain on Fleetwood Hill, supporting the Southern artillery, meaning that no significant force of Confederate cavalry gave chase. A frustrated Wade Hampton watched as Gregg’s battered division withdrew, largely unmolested.

Major McClellan noted, "Thus ended the attack of Gregg's division upon the Fleetwood Hill. Modern warfare cannot furnish an instance of a field more closely, more valiantly contested. General Gregg retired from the field defeated, but defiant and unwilling to acknowledge a defeat." After two hours of ferocious hand-to-hand fighting, Gregg reformed his command in the fields to the south of Brandy Station, where he had staged his initial attacks. "If anyone failed on this day to get all the fighting he wanted his appetite for fighting must haven prodigious," Gregg correctly observed after the war. He noted in his after-action report that, "The contest was too unequal to be longer continued. The Second Division had not come up; there was no support at hand, and the enemy's numbers were three times my own. I ordered the withdrawal of my brigades. In good order they left the field, the enemy choosing not to follow."

Thus ended the savage fight for Fleetwood Hill. The next day, Lee's Army of Northern Virginia kicked off its invasion of Pennsylvania that climaxed with the Battle of Gettysburg. Just seven weeks later, Fleetwood Hill saw another large-scale engagement between the competing cavalry forces, and then a third battle raged on October 11, 1863. In just over four months, three major battles occurred on the same piece of critical ground as the armies jockeyed for position along the Rappahannock River.

And to emphasize, the intense combat just related took place on Fleetwood Hill. And it was on Fleetwood Hill that the largest cavalry battle in American history took place, and it was at Brandy Station, and on Fleetwood Hill, that the war’s threshold campaign, the Gettysburg Campaign played out its opening scenes.

I would respectfully submit to each of you that there is no piece of ground in this country any more worthy of preservation than the "Famous Plateau," Fleetwood Hill.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...