The Mary Thompson House, Lee's Headquarters, was one of roughly 30 scenes photographed by Matthew Brady a week and a half after the 1863 battle.

Over the course of July 1, 1863, a simple stone house on Seminary Ridge was transformed into an icon of the Gettysburg Battlefield. Fierce fighting swirled around the structure, and when the ridge was taken by the Confederates, Gen. Robert E. Lee, recognizing its superb view in all directions, established his battle headquarters there, at the center of the Confederate lines.

Built by Michael Clarkson in 1833, the home was soon let to Joshua and Mary Thompson and their eight children, who were followed by a cloud of misfortune. Joshua, a drunkard, abandoned his family and subsequently passed away. In 1846, Clarkson ran into financial distress, but his good friend, future Republican Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, purchased the home in trust for Mary, making them co-owners until his death in 1868.

Following the battle, widow Thompson was left with little — her linens used for bandages and her fences for firewood. She moved from Gettysburg for a time but returned and lived out the rest of her years in the home, passing in 1873. When the Gettysburg National Military Park was established in 1895, the house, still privately owned, was not included.

The home came upon tough times. An 1896 fire damaged the interior but left the stone construction intact. Then, in 1907, the home’s tenant was arrested for keeping such a filthy house.

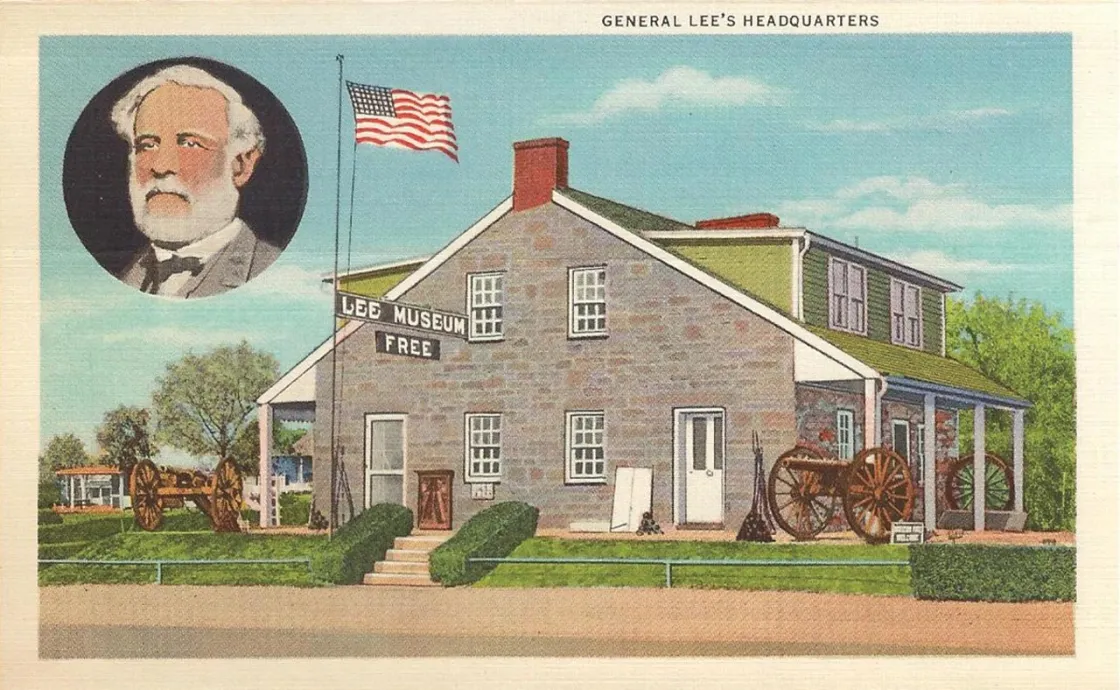

The gradual transformation of Gettysburg into a tourism mecca prompted the house’s transformation to General Lee’s Headquarters Museum in 1921. A nearby campground and cabins followed. Over time, a restaurant and Larson’s Motel — complete with swimming pool — surrounded the historic treasure.

But by 2014, with the facility’s franchise agreement with Comfort Inn set to expire, its owners approached the Trust about preservation options. With businesses operating at the site, confidentiality was paramount, and Trust staff began quietly planning the massive acquisition and restoration campaign they could only call Project X.

The effort was widely announced in time for the battle anniversary, and the Trust closed the $5.5-million deal on January 7, 2015. The next phase of the most ambitious project in Trust history was set to begin: bringing the home and its surrounding landscape back to its wartime appearance.

“Once we had the vision, I had to put together the plan to implement it,” said Matt George, the Trust’s land stewardship manager. “The first thing was getting approvals and permits for all of this, which took about a year.”

With nine buildings set to be torn down, requisite inspections were numerous and uncovered something unfortunate: seven buildings contained elements of asbestos — largely the dangerous, airborne kind — so a third of a year was spent on remediation alone. Once demolition began, great care was taken to ensure preservation of the two remaining Civil War structures on the property, the Thompson House and the foundation of the Dustman barn next door.

Archaeology was also critical. Despite two tombstones near the home, no human remains were present. The only Civil War artifact found was a minié ball some distance from the house, near the national park boundary. Other than that, scattered pre- and post-war knickknacks were uncovered.

Discoveries remain George’s favorite part of the project. When pulling out museum cases and post-war walls in the house, a second fireplace was exposed. A brick and earth berm around the building was removed, revealing two hidden basement windows. A number of the building’s original beams were uncovered — their provenance proved by the visible charring from the 1896 fire — and, once reinforced, were structurally sound.

But what guided the work? George points to Gouverneur K. Warren’s post-war topographical map of the entire battlefield. “Despite being post-war, it was so close that it was accurate.” In addition, 3-D versions of Mathew B. Brady’s mid-July 1863 photographs formed the visual inspiration for the garden, fencing and even a doghouse. Using these pieces in tandem formed a plan for the landscape and outside features surrounding the house.

Copper piping and fixtures were recycled. Asphalt parking lots were ripped up and hauled off. The old sewer and electrical systems were upgraded. Twenty-four apple trees were planted to re-create a historical orchard. A five-stop interpretive trail was installed. “We also reassessed the building’s foundation ... lowered the soil around it, re-pointed it and filled it back in,” said George, who remains thankful to this day for the brilliant team of Gettysburg-area companies that made the Trust’s biggest restoration project possible. “The only thing I take credit for is assembling a really great team — between the civil engineer, the demolition contractor, the restoration contractor ... they were all top-notch companies.”

The fruits of all this labor were put on full display on October 28, 2016, when 700 preservation-minded guests descended on Gettysburg for a rededication and ribbon-cutting ceremony.

As challenging as the process was, George looks back on the project proudly. “There was a point when you could go into the basement of the old restaurant and look straight up. For about 15 feet above you, there was nothing but dirt and debris, and I’m thinking ‘What kind of mess did you get yourself into, Matt?’ But you’d never know it today!”

With impressive historic value, Lee’s Headquarters is often considered the Trust’s flagship site at Gettysburg. It’s also a great place to start your tour of the legendary battlefield.

If you’re hoping for a look inside, the Trust opens Lee’s Headquarters to the public one Saturday a month between April and October, plus Remembrance Day in November. A fantastic partner, the Seminary Ridge Museum also augments access, with a docent opening the house every Friday during a 12-week period in the summer.

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...

Related Battles

23,049

28,063