Fort Washington

Fought on November 16, 1776 on Manhattan, the Battle of Fort Washington underscored General Washington’s disastrous New York Campaign. Just one in a string of defeats, the battle ended in a resounding British victory with the fort surrendering 3,000 Continental troops and Washington abandoning his defense of New York City.

With the British forces under the Command of General William Howe winning several victories during the previous summer in and around Long Island, Howe began to move on New York City beginning in mid-September. Though trounced by the British weeks prior at the Battle of Long Island, General George Washington was successful in checking Howe’s movements toward lower Manhattan at the Battle of Harlem Heights on September 16th. The victory was a boon for Continental morale, and at the time it looked as though the rising tide of redcoats had been stemmed.

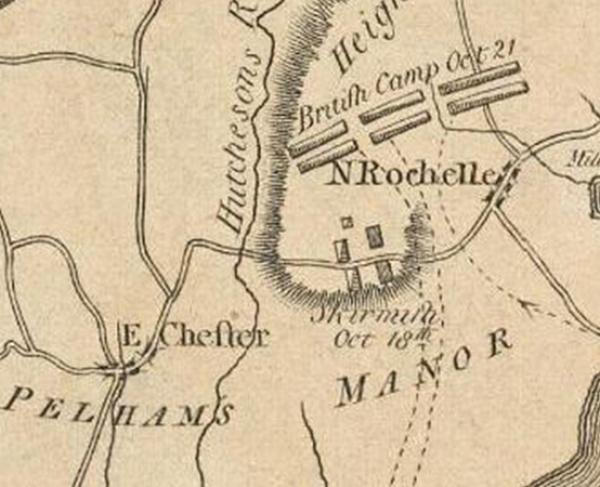

Howe, however, resumed the invasion of Manhattan with an added vigor as autumn approached. Sensing an opportunity to outflank and entrap Washington’s Army on the island, Howe successfully maneuvered around the Continentals’ right flank by landing a body of his force on the opposite side of the Hudson River on October 18th. Washington, fearing that his army would have no northern avenue of escape, mirrored Howe’s movement by retreating most of his force east across the river to White Plains, New York. Washington would not totally abandon Manhattan, but rather, he ordered General Nathaniel Greene to defend the island and Fort Washington with a force of nearly 1,200.

Fort Washington, though hastily constructed, wreaked havoc on British warships attempting to sail past the position overlooking the Hudson, and was similarly successful in repulsing Hessian attacks in early November at the outer rim of the fort’s defensive lines and redoubts. Unfortunately, these early successes would spell doom for the men defending the fort, as it gave General Greene and the commander of the garrison, Col. Robert Magaw, a false sense of the strength of the position.

Howe, moving north on the New York mainland, met Washington at the Battle of White Plains on the 28th of October, where the Americans suffered yet another defeat, resulting in a retreat further to the north, and away from Fort Washington, which was now left stranded on Manhattan.

Howe, ignoring Washington in retreat, wheeled his force around and bore down on Fort Washington overlooking the Hudson. The last American stronghold on Manhattan was completely alone as General Washington was now stuck on the opposite side of the Hudson unable to help.

As a precaution, Washington delivered a discretionary order to General Nathanael Greene to abandon the fort and remove Magaw’s garrison to New Jersey if the situation grew dire. However, bolstered by the prior minor victories over the combined British and Hessian forces, Magaw and Greene believed the fort could be defended, and declined to evacuate the fort.

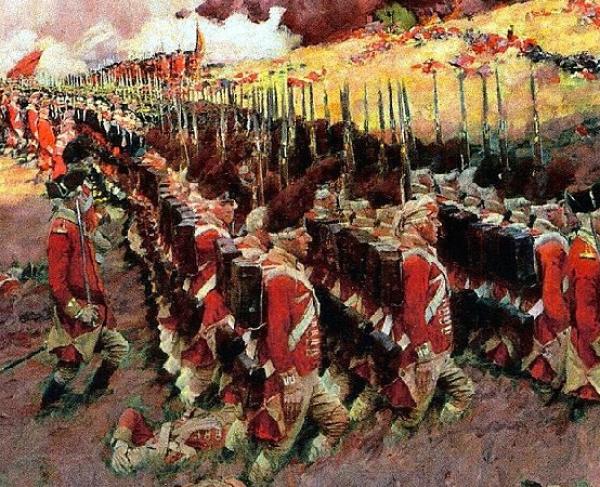

Seeing how precarious Fort Washington was with the body of Washington’s Army on the opposite bank of the river, General Howe initiated a three-pronged attack on Fort Washington and its outer defensive works. Before dawn on the 16th of November, Howe instructed General Lord Percy to attack from the South, driving north up the island and through the multiple lines of Continental defensive works, while he ordered General Matthews to cross the Harlem River with his force and attack from the eastern approaches supported by General Lord Cornwallis's infantry. The third prong of Howe’s attack would come from the east, with Hessian troops led by Willem von Knyphausen bearing down on the fort’s outer redoubts defended by Lt. Col. Moses Rawlings.

The combined British-Hessian assault grossly outmanned the defenders of Manhattan, with Howe brining at least 8,000 men to bear against Greene’s 3,000. Yet, the Continentals held out against probing attacks and heavy artillery for part of the morning. Rawlins’ Maryland and Virginia Riflemen were initially successful in repulsing the first two charges of Knyphausen’s Hessians, while other sections of the outer defenses inflicted heavy losses on the British forces moving into position for the combined assault.

Things quickly tumbled out of control for the Patriots when General Percy’s 3,000 man force punched through the outer defensive lines to the fort’s south. Almost simultaneously, Mathew’s and Cornwallis’ advance crumbled the eastern defenses, sending the Continentals scrambling back toward the last line of defense at Fort Washington.

Around this point of the battle, generals Washington – who had crossed over from Fort Lee to assess the situation – Greene, Putnam, and Mercer, were urged to evacuate the island lest they run the risk of falling into enemy hands given the deteriorating situation. Encouraging Magaw to hold out until nightfall when at least some of he and his men could slip away, Washington and the other ranking generals made their escape across the Hudson avoiding capture.

With the outer defenses breached and hemmed in on all sides by a greatly superior force, Magaw realized the situation was hopeless. At 3:00 pm after a fruitless attempt to gain gentler surrender terms for his men, Col. Magaw surrendered Fort Washington and the 2,800 defenders left standing to the British. The fall of Fort Washington made Washington realize that the campaign for New York was all but over, and he withdrew his battered army south into New Jersey. Though he lost nearly 3,000 men in defense of the fort, the army was still intact and would live to fight another day.