German Prisoners of War in Gettysburg

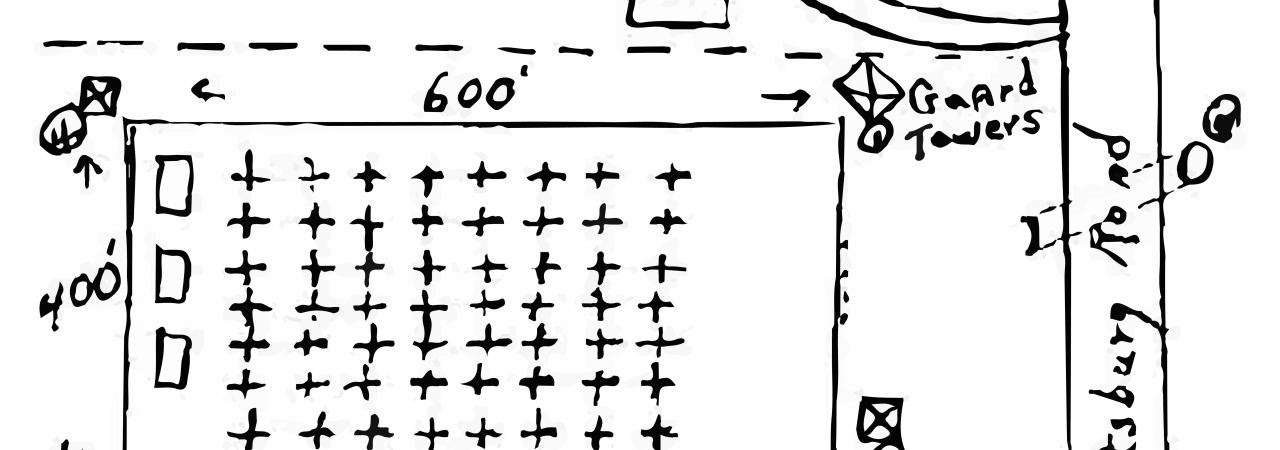

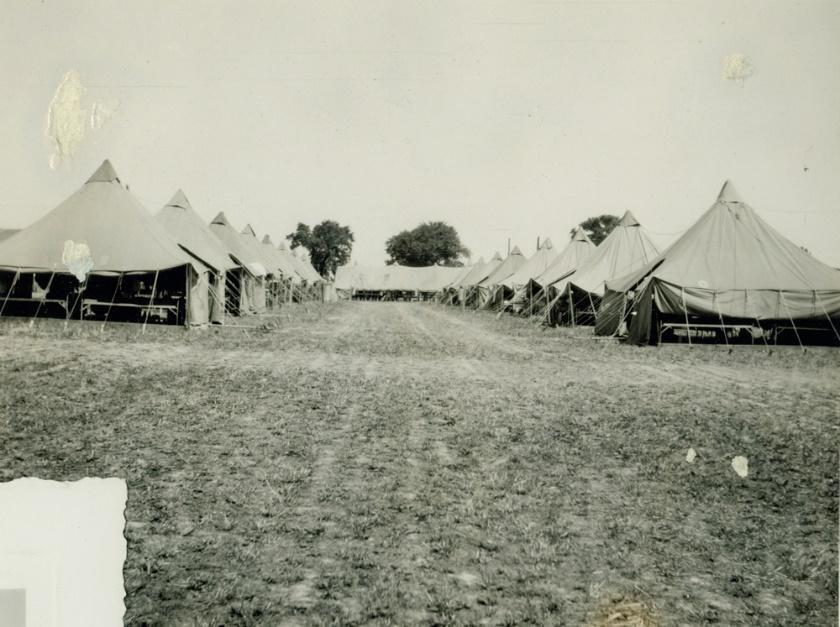

A gathering of prisoners of war in Gettysburg doesn’t sound like a surprising topic at first glance. However, the soldiers in this camp were not Union or Confederate, they were Germans captured during the Second World War! During the Fall of 1942, the War Department agreed to house German prisoners of war on American soil, leaving the government with the question of where exactly to house them. Approximately 500 camps were eventually formed. One such camp was within Gettysburg National Military Park; its relatively remote location made the site attractive for use as a prisoner camp. Additionally, existing facilities in the form of an old Civilian Conservation Corps camp and nearby labor shortages caused by the war made the selection more attractive. Located along the west side of the Emmitsburg Road, south of the Home Sweet Home Motel and Long Lane, the camp was built by fifty German prisoners sent from Fort Meade, Maryland. While building the new camp, the prisoners were housed in the old National Guard Armory also situated on park property. On June 2, 1944, the main contingent of prisoners arrived, and the camp soon held up to 400 prisoners of war while staffed with 60 enlisted men and 5 officers as guards. The camp sat among the fields that witnessed Pickett’s Charge, in the shadow of the Virginia Memorial.

Arriving German prisoners quickly found themselves put to work, as both then and now Adams County had no lack of agricultural industry. Any farmer, packing company, or orchard owner could apply to the local employment service, which coordinated contracts between local farmers and the military. The labor shortages in Adams County, Pennsylvania had become so bad that the U.S. Employment Service described it as “very acute,” as there were 150 urgent requests for labor on top of 300 to 500 standing requests. The initial group of prisoners were assigned to “fourteen canneries, both fruit and vegetable; three orchards, seventeen farms, one stone quarry, and one fertilizer and hide plant.” The prisoners were always guarded and transported to various locations in Littlestown, Biglerville, Hanover, Chambersburg, Middletown, and Emmitsburg. The employers paid $1.00 an hour; the majority went to the government while 10 cents were credited to the prisoners in the form of coupons that could be used at the post exchange, as officials worried that giving prisoners actual cash would fund escape attempts. After the vegetable season, the prisoners shifted to cherry or apple harvesting. Both these assignments were rather popular, as prisoners ate while they worked, and often smuggled pockets filled with fruit back to camp. When harvest season ended, many prisoners we moved elsewhere, and the number of prisoners diminished. Down from 400 to 200 prisoners, these remaining Germans were moved from the tent camp to the old Civilian Conservation Corps barracks for the winter and given unpopular tasks such as cutting pulpwood and clearing underbrush on the battlefield.

German prisoners were generally contained within the boundaries of the camp at Gettysburg. The United States government dedicated large amounts of both time and money to provide prisoners with both the mandated necessities as well as luxuries such as movie nights and classes worth college credits. One prisoner later returned to visit the plant he worked at during the war both to visit old coworkers and get a better look at the design, as he worked in construction in Germany and wished to emulate the design. Another prisoner, Carl Brantz, remembered his experience fondly and returned in 2001. Assigned to the woodcutting team, he served as an interpreter, and said that even if he could, he “would give back not one little thing.” Germans found the United States far different than Nazi propaganda had envisioned it. Some prisoners said that they “had purposefully surrendered to the Americans to get a chance to see America and to be safe from the battlefield,” and many claimed to be conscripts who had never fired a shot. One had even surrendered and proceeded to save the lives of several wounded Americans immediately after. In fact, German prisoners were sometimes seen as treated too well, leading to backlash from American civilians who commented that prisoners were “well fed and living the good life while brave Americans were ‘neglected and starving,’ [and those] feelings were exacerbated as Nazi atrocities became known at the war’s end.”

However, there were also incidents at Gettysburg indicating that proper regulations had not been followed. The camp was said to have trash visible, homemade stoves that presented a fire hazard and had not “allowed the prisoners to make up cards,” as they were not available to the prisoners for 60 days. Although the stoves likely had made the lives of the prisoners easier, they could not have been thrilled at being unable to write home for two months. Overall, the Germans had ample opportunity for leisure, and residents remembered seeing them “sitting on the steps of the Armory playing guitars, playing cards and drinking beer” or even playing soccer and singing opera. They worked hard but were able to unwind afterward and either relax or further their education, and even prisoners looked back on their imprisonment without much regret.

The local response to the arrival of German POWs was generally mixed. Newspaper articles ranged from begrudging acceptance to calling for local farmers to keep their hunting guns oiled and loaded in preparation for Nazi treachery. As camps were divided by rank, political association, and nationality, Gettysburg’s camp tended not to hold staunch Nazis which likely eased local tensions. Although interaction between townspeople and prisoners was forbidden, that was a rule that generally fell by the wayside. Prisoners would often talk to the Americans who worked beside them, as “most of them could speak some English as well as carry on a conversation [and] would like to talk to people to gain knowledge of the area.” Eventually, Captain Thomas, one of the American officers, became tired of locals gawking at the prisoners, and gave an interview mentioning that “the nuisance of women loitering about the camp had let up considerably but that an alert lookout is being maintained to prevent a recurrence of the habit of many women driving to and remaining near the camp site.” The German prisoners were seen less of as a threat or as an enemy, but rather as a generally harmless curiosity. Even managers who had hired the prisoners looked upon them in a positive light. A local farmer mentioned that he enjoyed giving the Germans cigarettes and allowing prisoners to eat the fruit they harvested; it made them get more work done!

This isn’t to say that there were never any real conflicts between prisoners, guards, and civilians, as issues ranged from the humorous to the severe. Staff at the B. F. Shriver Canning Company in Littlestown, PA had contracted out prisoners to work packing canned vegetables into cartons and then store them in the warehouse. At some point during the summer of 1945, it was found that the Germans had been stealing sugar that was to be used in the canning process. While on the way back to the camp, the prisoners’ lunch bags were checked, and over 100 pounds of sugar were recovered. When asked what the sugar was intended for, the Germans simply responded that “they used the sugar in a process to make home brew.”

Though there was little fear of escape, a few notable events made the camp the center of more dramatic events. On July 5, 1944, two prisoners, Thomas Kostaniak and Axel Ostermaier, used the drainage pipe beneath the Emmitsburg Road to escape towards the High Water Mark. They were captured on July 11 in a farmhouse near York, and taken into custody without resistance, having been distracted until police arrived by a farmer who was feeding them. They were described in good condition, having lived off local orchards, with one merely “badly in need of a shave.” It was remarkable that they had evaded capture for so long, as they had no money, did not speak English, and were wearing the denim uniforms and raincoat that had “P.W.” stenciled on them. A smaller escape was also detailed in the local paper. Two men in prisoner of war stenciled clothes were found on the curb in front of The Plaza restaurant, now the location of the popular Blue and Gray Bar & Grill. Officers in town thought they looked familiar and picked them up to return them to the camp.

The final escape occurred in early 1946. The war was technically over, but the repatriation of POWs was being delayed until their labor was no longer needed and logistics allowed for transportation to Germany. Hans H. Harloff and Bernard Wagner escaped the camp by slipping under the barbed wire at a corner of the camp at 10:50 PM on January 3. However, when asked about their reason to escape, they answered simply that they “liked America, wanted to see more of it and hoped to reach a large city and stay in this country rather than return to Germany.” This escape led to a great deal of local drama, as three locals were arrested for helping the prisoners. Byron Cease, his wife, and his daughter Pearl were all arrested, as they had given Harloff and Wagner “food, clothing and assistance” as well as the location of an abandoned home. Apparently, Pearl met one of the prisoners while working at the canning factory and they smuggled notes back and forth. After escaping, the Germans anticipated they would find help there. Although the family was arrested, the local judge decided to release them, as the war was over and “a period of imprisonment would serve no good purpose in view of the good reputation bourne by the family in Adams County.”

In addition to escape attempts, somber events at the camp included two deaths. On the evening of November 8, 1944, 38-year-old German Private Georg Hartig was found dead at the Adams Apple Products Corporation plant in Aspers. He was found hanged from a rafter on the second floor of an apple shed. On September 1, 1945, the body of American camp guard PFC Joseph F. Ward was found at about 10:20 AM in one of the camp’s guard towers. The Adams County coroner reported that he had been dead for only 5 minutes when he had been found with a .30 caliber carbine wound to the head. As the bullet had torn a hole after exiting Ward’s head, it is possible that he had killed himself or it may have been an unfortunate accident.

Ultimately, the POW Camp at Gettysburg was a successful operation. The camp provided much needed labor for the Gettysburg area, and it raised thousands of dollars for the federal government, essentially paying for itself. Whether it was hundreds of prisoners harvesting in the summer or a lesser number clearing brush in Gettysburg National Military Park in the winter, necessary labor was carried out at low prices. The German prisoners remembered their captivity fondly, considering imprisonment at the hands of Americans as far preferable to fighting. They lived in relatively good conditions, enjoyed leisure activities, took advantage of opportunities for education, and earned wages. The area was strange, but enticing, and the local people made fascinating co-workers to the Germans. The area was generally accepting of the arrival of what they considered a curiosity rather than enemies. Despite short-lived escapes and tensions caused by those events, many of the stories about the camp show that it was a place where Germans acclimated to American society as well as a place where Americans cooperated with their adversary.

Further Reading:

- ’The Prisoners Are Not Hard to Handle:’ Cultural Views of German Prisoners of War and Their Captors in Camp Sharpe, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.” By: Elizabeth Atkins

- On A Great Battlefield: The Making, Management, and Memory of Gettysburg National Military Park, 1933-2013. By: Jennifer Murray

- "Prisoner of War Camps at Gettysburg During World War II" By: National Park Service

Related Battles

23,049

28,063