The Guilford Battleground Company

"Guilford Courthouse [National Military Park], the first Revolutionary War battlefield set aside as a national park, is important not only for the event it was established to commemorate, but also for its role in the development of the American historic preservation movement."

Thomas E. Baker, "Redeemed from Oblivion: An Administrative History of Guilford Courthouse National Military Park."

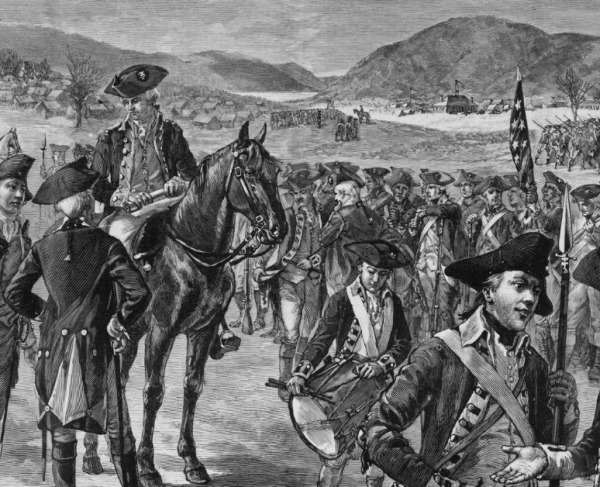

Despite being remembered as a British tactical victory, the outcome of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse highly favored the Patriot cause. Fought on March 15, 1781, the British suffered 25% casualties, a significant blow to their forces. Weakened after the battle, British General Charles Cornwallis abandoned his campaign to secure British victory in the South. Many historians agree that the Battle of Guilford Courthouse can be credited with leading to the eventual British surrender at Yorktown, because it was after this battle that General Cornwallis turned towards Virginia, where he would surrender in October.

In the period immediately following the end of the American Revolution, some suggestions were made to preserve the battlefield where the Battle of Guilford Courthouse was fought, but no action was undertaken.

In 1881, Judge David Schenck moved to Greensboro, North Carolina, to become General Counselor for the Richmond and Danville Railroad. While undertaking this position in Greensboro, Schenck often found himself stopping at the nearby deserted battlefield to look over the land. At this point, the battlefield had long been left untended, and he found it overgrown and covered in brambles.

Taking a keen interest in the battle and the land, Schenck sought information from fellow Greensboro citizens about the events that had transpired there 100 years prior; however, there were few people who could give him any insight into the pivotal battle. Schenck began studying maps and accounts of the battle to educate himself about the history that had unfolded there. He became invested in the accounts of the battle and the crucial role that his own statesmen had played in securing eventual British surrender. In October 1886, as Schenck habitually walked the battlefield, he was inspired, and scrawled in his diary that he was determined to purchase the land in order to preserve it and, as he said, “Redeem the battlefield from oblivion.”

On the same day, Schenck bargained with the owner of much of the battlefield land to buy 30 acres for $10/acre. Operating on his own whims and at his own expense, Schenck proceeded to purchase 20 more acres of the land at the cost of $20/acre. Realizing that his mission required help, he rallied many of his acquaintances from the community to join him in his efforts to preserve the battlefield. In 1887, he organized the group into a coalition of like-minded individuals working to preserve and restore the battlefield and the legacies of the Patriots that fought there.

The group petitioned the North Carolina legislature for a charter, which was ratified in March of 1887, and created the Guilford Battleground Company (GBC). Their primary goal at the time was to raise enough money to purchase all the land on which the battle had occurred, preserve it, and then transform it into a park where they could erect monuments and memorials. In their first few years, the GBC operated without federal aid and relied on the generosity of private citizens and companies to achieve their goals. To make the majority of their money, the GBC sold stock in the company for $25 per share, and by 1893, had 100 stockholders. Hoping to make walking the battlefield a more peaceful experience, the GBC cleared the brambles and leveled much of the land to plant a field of oats and trees. The GBC fought hard for their cause, publishing their intentions in circulars and mailing them to citizens in the area, asking for donations. The response to the GBC was positive, and many private citizens became invested in the cause, giving money and support for the mission.

The GBC hosted a 1-year anniversary party on the battlefield in May 1888 to celebrate their progress. With 15,000 attendees, the event was a huge success. GBC President David Schenck gave a powerful speech, explaining the events that had transpired at the battle over 100 years prior. Schenck motioned to all corners of the battlefield enlightening his fellow citizens about the locations of the battle and the importance of preserving it. He spoke passionately about their forefathers and the importance of honoring their bravery. He spoke to the hearts of the many native North Carolinians, explaining it was their state, and their men, that turned back the British, in what he called “the most important battle of the war.”

Schenck ended his rousing speech by gazing out on the battlefield and reaffirming the mission of the GBC by imploring his fellow citizens: “Let us hold [the land] as a sacred heritage from our fathers, as a shrine of liberty, where all may worship in the generations which shall continue to the end of time.” The speeches gave rise to more support for the preservationist movement. The actions of David Schenck and the Guilford Battleground Company were some of the first within the United States to preserve battlefields from the American Revolution.

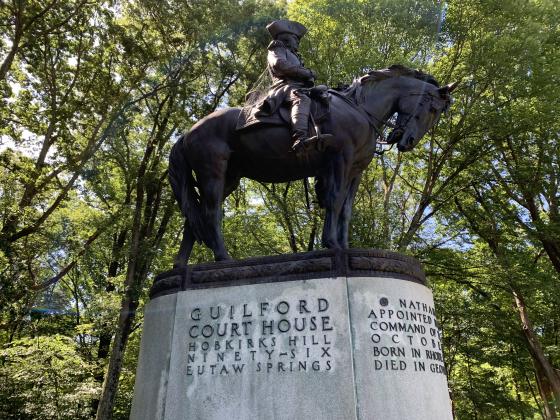

The GBC movement still continued even after the death of its founder in 1902. Within their first 30 years, the GBC purchased 150 acres of the battlefield, including the site of the courthouse, and erected 27 monuments on site. They built a museum on the grounds to advance the opportunities for education about the battle. In order to make the battlefield a shrine for Patriots, they also reinterred, on the battlefield grounds, the bodies of multiple North Carolinian Patriots, who had signed the Declaration of Independence.

In 1917, legislation was passed which made the Guilford Courthouse battlefield the first American Revolutionary War site to be preserved by the Federal government. That same year the Guilford Battleground Company deeded 125 acres of the battlefield to the War Department for continued protection. At that time, deeming their mission a success by making the battlefield a National Preserve, the GBC disbanded.

After the GBC disbanded, the War Department planted shrubbery, hoping to beautify the Park, newly named the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park. The War Department continued to erect monuments throughout the Park as well. In 1933, the park was officially entrusted to the Department of the Interior's National Park Service (NPS), who undid all the modern landscaping and restored the battlefield to its wartime condition.

Unfortunately, the NPS took few further efforts to preserve or promote the National Military Park. Urban developers began to encroach on the battlefield land, building on some of the unpreserved land on which the battle had taken place. Met with passivity from the NPS and encouragement from the local government, these developers created convenience stores and housing developments on the boundaries of the park. Tragically, because the importance of the National Military Park was not affirmed by the NPS, the grounds and monuments were often the targets of vandalism and theft. The legacy of the battlefield went unacknowledged, and the NPS, who was entrusted to protect the park, made little effort to support it.

In the 1980s, developers began swarming the area around the Joseph Hoskins House, near where the British had formed their first battle line, hoping to turn the land into a shopping center. During this time, angered by the apathy of the NPS and the flagrant disrespect by many towards the battlefield, like-minded citizens came together to revive the Guilford Battleground Company and save the endangered land from destruction. The modern GBC raised money from the community to purchase and preserve the at-risk 7.5-acre Hoskins homestead. With the help of concerned citizens and a leadership grant from the Tannenbaum-Sternburger Foundation, the GBC was successful in its mission and established the newly saved land as the Tannenbaum Historic Park. Eventually, the GBC successfully established both Parks as National Historic Landmarks in 2001.

The National Park Service published an administrative history of the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park in 1995 to reflect on their past actions and learn from their failures, so as not to repeat them. Their self-reflective history outlined the irresponsible past maintenance of the National Park and the unfortunate lack of action on its behalf by the NPS. At the end of the publication, the author, Thomas E. Baker, asserts that the most important lesson he learned was the need for individuals who strongly believe in preserving these sites, and who will advocate on their behalf, even if it means standing up to the local government or the NPS. These advocates are strong today, existing in the modern GBC, in the American Battlefield Trust, and in all like-minded preservationists who seek to honor the sacrifices of those who fought for our liberties.

Today, the Guilford Battleground Company has new goals for the Park, hoping to preserve surrounding land that they have determined to have been part of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. The land that they hope to protect is 5 times larger than the 200 acres that they currently have preserved. While some preservation victories have been won, these areas are currently targeted by developers, and the GBC is fighting to raise money to purchase these important battlefield lands.

Further Reading:

- Long, Bloody, and Obstinate: The Battle of Guilford Courthouse By: Lawrence E. Babits and Joshua B.Howard.

- Redeemed from Oblivion: An Administrative History of Guilford Courthouse National Military Park By: Thomas E. Baker.

- North Carolina 1780 - 81 By: David Schenck.

Related Battles

1,310

532