In 1776 the British hired German troops to help supplement their army in the war against America. At this time though, Germany was not a unified nation. Instead, it was divided into numerous different principalities that operated independently. With warfare constantly occurring around the globe in the eighteenth century, the princes of many of these nation-states would offer their soldiers and armies to fight in return for monetary compensation. The troops would serve as auxiliary troops to the British Army and were not mercenaries in the strict sense of the term. They fought in their own units, commanded by their own officers, with their own flags and uniforms, and were loyal to their individual princes. They were professional soldiers and were paid for their service and would reap additional profit from looting and plundering the American countryside.

The German states made for natural allies for the British Army. There were numerous familial ties between Great Britain and the German states. In fact, the king of Great Britain, George III, was part of the House of Hanover and his grandfather had been born in Germany and his wife was also from Germany. The renting of armies by the German states was a large source of revenue for their principalities. Their armies were known across the world to be among the best and most disciplined. Once in the German armies, discipline was extraordinarily harsh and difficult, but in many cases, they came to take immense pride in their units and fellow soldiers.

The British ended up using more than 30,000 German troops during the Revolutionary War, and these made up about a quarter of all the troops in the British Army. German soldiers fought in Revolutionary battles all across the American continent. These German auxiliaries were known throughout the conflict commonly as Hessians. This term is derived from the fact that the majority of the German troops came from the states of Hesse-Cassel and Hesse-Hanau. However, there were also German troops that came from the states of Brunswick, Anspach-Bayreuth, Waldeck, and Anhalt-Zerbst. The first Hessians arrived in America in New York in August of 1776. Of the 32,000 men in that British expeditionary force, nearly 8,000 of them were Hessians.

The Americans were outraged at the idea of King George III hiring foreign troops to subdue them and specifically called this practice out in the Declaration of Independence. Among the grievances leveled at King George III in that document was that: “he is at this time transporting large armies of foreign mercenaries to complete the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of cruelty and perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the head of a civilized nation.”

While the Americans often painted the Hessians as bloodthirsty mercenaries, in reality, many of the Hessians were forced into the army against their will. Many men in these states were forced to join the army, or their livelihoods depended on it.

These Hessians fought exceptionally well in the New York Campaign during the late summer and early fall of 1776. Unlike the red-coated British soldiers, the Hessians typically wore coats of blue or green. The grenadiers wore tall gold miter caps that made them appear taller than they already were. After the initial fighting on Long Island, rumors quickly spread across the continent of their ferocity and savagery. Stories abounded in American camps that the Hessians gave no quarter to surrendering soldiers. American riflemen were found on Long Island impaled to trees by Hessian bayonets and a British officer noted how: “The Hessians and our brave Highlanders gave no quarters, and it was a fine sight to see with what alacrity they dispatched rebels with their bayonets, after we had surrounded them so that they could not resist.”

Occasionally though, their British allies looked with derision and suspicion on the Hessians. Part of this was the language and cultural barriers and the desire by both armies to distinguish themselves and attain glory.

On November 16, 1776, thousands of Hessian soldiers charged at Fort Washington and took the fort at the point of the bayonet. Perhaps the most famous action though, that involved Hessian soldiers was the Battle of Trenton, which occurred on December 26, 1776. A brigade of Hessians under the command of Colonel Johann Rall was stationed at Trenton following the successful New York campaign. While overconfident and underprepared, contrary to popular belief Rall and his men were not drunk or hungover from a Christmas celebration when the fighting started on December 26. On that day nearly a hundred Hessians were killed or wounded, including Rall, and 900 were taken prisoner in a battle that ultimately changed the course of the war.

The British blamed the Hessians for this ignominious defeat. It was here that the first stories of them being drunkards began to appear. The British attempted to blame this fluke on the idea that the Hessians were not as good soldiers, however, the Continentals then defeated the British at the Second Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton.

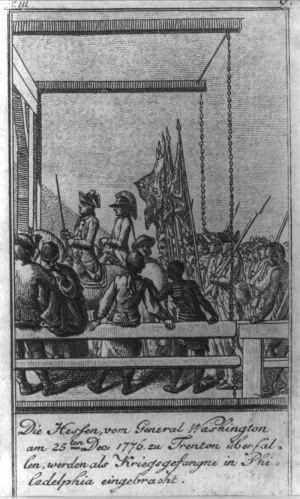

After the battle of Trenton, the Hessian prisoners were marched through the American capital in Philadelphia, where residents eagerly looked at the soldiers they had heard so much about. Hessians captured at Trenton and other battles were sent to prisoner of war camps in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

The western parts of those states actually had a large German immigrant population already, and many Hessians actually found that they preferred life in the Americas. Away from the harsh discipline of military life and with people who spoke a similar language and had a similar culture, many Hessians would desert and stay in America following the war. By the end of the war, tens of thousands of Hessians ended up staying in America.

Perpetuating the myths of the Hessians, they are still often remembered as drunks and mercenaries in popular stories. Perhaps the most popular story of a Hessian was written forty years after the war by Washington Irving in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” The Headless Horseman story follows “the ghost of a Hessian trooper, whose head had been carried away by a cannonball.”

While the Hessians still live with us in popular culture, maybe their greatest legacy is the thousands of Americans who, perhaps unknowingly, are descended from these men who came across the ocean to help in subduing the Revolution and ended up becoming American citizens.

Further Reading:

- Hessians: Mercenaries, Rebels, and the War for British North America By: Brady J. Crytzer

- The Hessians and the Other German Auxiliaries of Great Britain in the Revolutionary War By: Edward J. Lowell

- A Hessian Diary of the American Revolution By: Johann Conrad Döhla, edited By: Bruce E. Burgoyne

Related Battles

5

905

1,310

532

1,111

533