It’s hard to talk about the Revolutionary War without invoking the term “bold,” as rising against a global colonial power is not for the faint of heart. Innovation in warfare, especially in the medicinal, scientific, and engineering fields, was — and remains — a natural occurrence. But with George Washington’s Continental Army out armed, outmanned, and outmatched by the British at almost every angle, the Continental Congress did more than fund a guerilla war, it welcomed non-conventional tactics and odd inventions. This bold mindset allowed one inventor’s ideas to flourish and change the game of naval warfare forever. This is the story of the Turtle, the first combat-deployed submersible vessel.

An Inventor from Humble Origins

David Bushnell’s origin story embodied the American dream decades before the United States was an inkling in the mind of its founders. He was born to farmers, Nehemiah and Sarah Bushnell on August 30, 1740. Growing up in the rural outskirts of Saybrook, Conn., Bushnell assisted his father and brothers with fieldwork and general farm maintenance, but spent his free time reading, cultivating curiosity and a love of invention.

But it took time and tragedy before Bushnell could tap into his academic passions. At 26, he remained unmarried and living at home. But in the course of just three years, he lost two sisters and both parents. Seizing an unforeseen opportunity in the face of grief, Bushnell used half of his inheritance to pursue an education and, at age 31, he was accepted at Yale College.

His focus of study at Yale? Igniting gunpowder underwater — a feat which generally thought impossible prior to his experiments. At first, he was only able to detonate about two ounces of gunpowder underwater but, by the time he left Yale, Bushnell had crafted mines that could detonate up to two pounds of submerged explosives. The only thing Bushnell was missing was a vehicle that could stealthily transport his mines.

The Plight of the Turtle Submarine

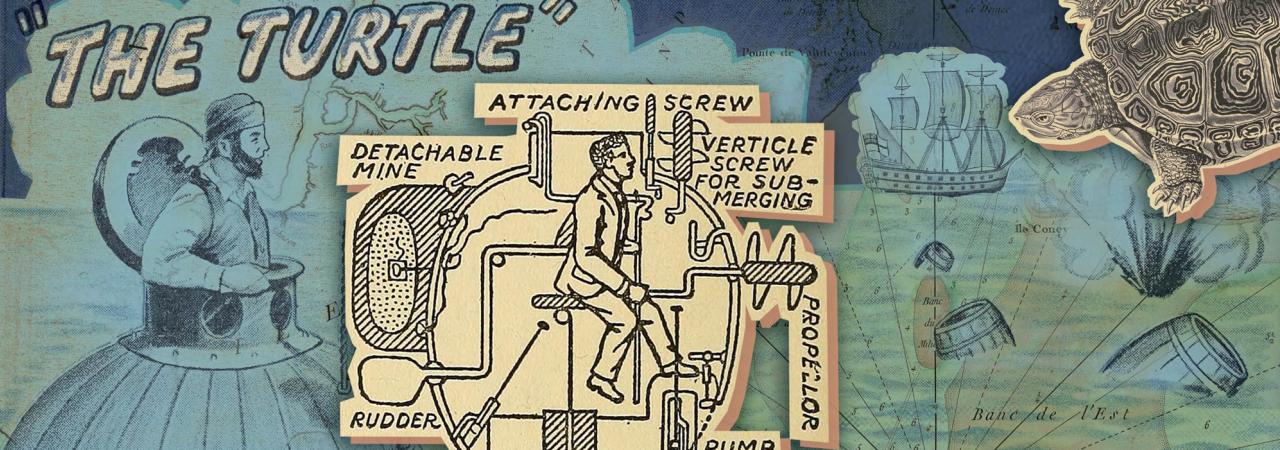

After graduating from Yale in July 1775, Bushnell returned home to his brother’s Saybrook farm and the pair got to work creating the contraption that would transport and plant the mines. In a detailed 1787 letter to Thomas Jefferson,Bushnell described his craft thus:

“The external shape of the sub-marine vessel bore some resemblance to two upper tortoise shells of equal size, joined together; the place of entrance into the vessel being represented by the opening made by the swell of the shells, at the head of the animal.”

One of Bushnell’s Yale colleagues, Dr. Benjamin Gale, invited his personal acquaintance, fellow inventor Benjamin Franklin, to visit Bushnell and view his new creation. From this visit onward, Bushnell’s association with the Continental war effort grew as his network expanded. By the summer of 1776, George Washington himself met with Bushnell to arrange for the transport and operation of the craft now dubbed the Turtle. Although early submarines were concocted by Dutch inventors in the 1620s, the Turtle was more than just the first American example: it soon pioneered submerged naval combat.

The Turtle’s first and most famous contact with the British occurred in September of 1776. The plan was to covertly approach the HMS Eagle, infiltrate underneath it, attach a bomb to its underside with the assistance of boring tools, and then float away in time for the explosive to sink the British warship. But due to poor health, Bushnell could not pilot the mission and the volunteer captain, Sergeant Ezra Lee, had only basic training for operating the intricate machinations of the Turtle. Adding a layer of difficulty, the vessel only had enough air to be submerged for 30 minutes. Lee's struggles to attach the bomb were probably due to a combination of stress, confusion and accidental carbon-monoxide poisoning.

Lee ended the mission by floating away from the ship and letting the mine explode downriver, where it failed to harm either himself or the HMS Eagle. The other two attempts undertaken by the Turtle are not as well documented, and the submarine was unfortunately taken out of commission when the American sloop transporting it was sunk by British forces at the Battle of Fort Lee. The Turtle was salvaged but, due to budget constraints, was not able to be repaired and used again.

Bushnell, Genius...or Fool?

The wretched death of the Turtle was not the end of Bushnell’s involvement with the Continental Army. He also attempted to create a river mine network to stop British ships from floating into the former colonies’ interior. While this task was mostly unsuccessful, Bushnell’s innovative keg mines were deployed in a January 1778 attack on the British fleet in Philadelphia harbor immortalized by poet Francis Hokinson as “Battle of the Kegs.” The introverted inventor served the rest of his days in the Continental Army as a sapper and engineering captain.

It can be easy to critique Bushnell if one forgets the circumstances, lack of time, budget and resources under which he worked. During a different time, at a different place, there’s a strong chance that we could have seen Bushnell’s brilliance fully shine. Still, his genius must be recognized as the father of modern submarines and naval mine warfare for good reason. Bushnell is credited for the invention of the screw propeller as well as the use of water ballasts, both components that are used today in modern submarines. The U.S. Navy even recognized Bushnell for his services by naming two submarine tenders after him in 1915 and 1945.

Remembering the Turtle Today

Thanks to people’s passion for bringing the past to the present, there have been a number of Turtle recreations in modern times – some official and some illicit. Notable examples include:

- Joseph Leary and Fred Frese co-founded a recreation Turtle project in 1976 to celebrate the United States Bicentennial. The vessel was christened by Connecticut’s then-Governor Ella Gasso and was tested in the Connecticut River. Today, it is owned by the Connecticut River Museum in Essex.

- Rick and Laura Brown of Handshouse Studio were aided by the U.S. Naval Academy in authentically recreating the process by which the vessel was built in the Revolutionary era. This replica can be found in the International Spy Museum lobby in Washington, D.C.

- In August of 2007, three men were stopped by the police while piloting a Turtle replica near the RMS Queen Mary 2 in Brooklyn, N.Y. The New York Times noted the vessel “resembled something out of Jules Verne by way of Huck Finn....’”