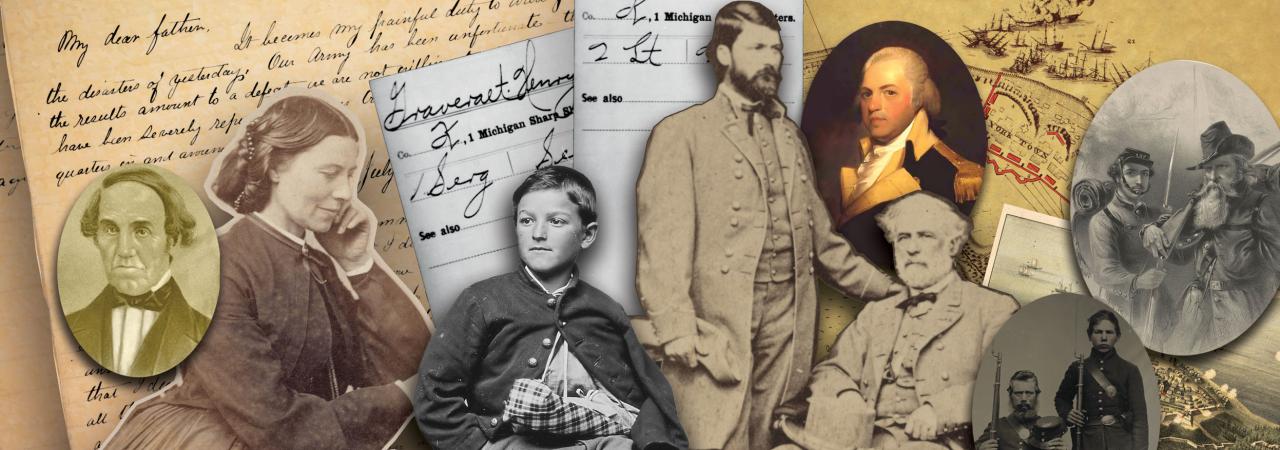

In some families, military service is a true legacy, with service spanning conflicts and causes. No matter differences in age, experience, or gender, their service acts as a common thread that binds them together. Take a look at some fascinating father-child duos that went beyond simple family ties to establish a unique relationship — a fellowship of service under the same roof.

Colonel Samuel McDowell and Sons

Samuel McDowell’s military service began during the French and Indian War, when the young man in his early 20s, participated in the 1755 Braddock Expedition. The venture culminated in the Battle of the Monongahela, an encounter that pitted British forces against an irregular army — largely composed of French-allied Native American warriors — defending Fort Duquesne, the strongest French fortification in the Ohio Valley. To the surprise of the British, this irregular army proved a resilient force that pushed them back, ultimately resulting in British withdrawal.

McDowell continued his service to the British in Lord Dunmore’s War, during which he was appointed aide-de-camp to future Kentucky Governor Isaac Shelby. His loyalties changed leading up to the Revolution and McDowell was made colonel of a Virginia regiment that fought under the direction of General Nathanael Greene during the Southern Campaign — he was even present at the decisive Battle of Yorktown in 1781. Throughout the Revolution, McDowell was joined by his two eldest sons, John (a major) and James (a private). Although his offspring were in different regiments, they sometimes met on the same battlefield... as was the case at Yorktown!

In the War of 1812, Col. Samuel McDowell’s sons James (who rose to the rank of colonel) and Joseph (a colonel) continued the McDowell tradition of military service. Furthermore, James’ son — Samuel’s grandson — Capt. John Lyle McDowell, also fought in that second war against Great Britain.

Capt. Stephen Barton and Clara Barton

Today we remember Clara Barton as a model of bravery, as she charged onto the Civil War scene to care for wounded soldiers and deliver vital supplies to the Union Army. While not in military service, she provided Union forces with essential supplies and services when demand was at its highest and morale was at its lowest; she was a force of her own. It can be reasonably speculated that Barton’s dedication to the cause stemmed from hearing her own father’s war stories.

America was in its infancy when Capt. Stephen Barton marched from his home in Oxford, Mass., to Detroit, Mich., and enlisted for three years under Maj. Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne during the Northwest Indian Wars of 1785-1795. Captain Barton thrilled Clara, his youngest child, with lessons in geography, military tactics, and the significance of equipping an army with arms, food, clothing, and medical supplies. Clara Barton’s relationship with her father laid the foundation for her becoming the “Angel of the Battlefield,” as he instilled a deep-rooted patriotism in his daughter. He himself once remarked that, when the Civil War began, Lincoln should have called for 200,000 men — instead of 75,000. Clara did not hesitate to jump into action, acting as one of the first volunteers to care for the wounded at the Washington Infirmary and on the battlefield, following Bull Run, in 1861. However, her first official field duty took place after the Battle of Cedar Mountain in August 1862. Her outspoken spirit may have also been inherited, as her father was known for his giving to the less fortunate and serving in public office, where he voiced his belief in abolition and the power of education. Clara’s heartfelt legacy lives on today through the organization she ardently founded in 1881 — the American Red Cross.

Sgt. Henry Graveraet and Second Lt. Garrett A. Graveraet

The father-son duo of Henry and Garrett A. Graveraet fought side-by-side in a number of Civil War engagements... at places like the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and in the Petersburg Campaign. Even more fascinating: they both served in Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters — a group that largely consisted of Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi soldiers. With men recruited out of Kalamazoo and Dearborn, Michigan, Company K became the largest unit of American Indians serving with the Union armies east of the Mississippi River.

Garrett was a well-known and well-educated young man — not the stereotypical soldier! With a passion for literature, art, and music, the young Graveraet was a violinist, as well as a portrait and landscape painter. He also straddled two worlds: His father was a Franco-Ottawa merchant and his mother was Ojibwa. Garrett spoke English, French, and Ojibwe, even having taught briefly at a native school. Many described him to be a natural leader and an expert in cultural mediation. So, when Native American participation in the Civil War was permitted in 1863, the man of many talents became an officer and led an impressive recruitment drive — even signing up his own father, the 55-year-old Henry, who shaved off 10 years from his true age during enlistment.

The emotion experienced when charging into battle alongside a person you’d do anything to protect is difficult to fathom; but their loss must be even harder. During entrenched operations at Petersburg in June 1864, Garrett saw his father shot dead. One account says that the young officer fought back tears and dug Henry’s grave with nothing but an old tin pan. He returned to lead his men in battle but, that very same day, received his own fatal gunshot wound.

Roughly 68 percent of Company K perished during the war, demonstrating fierce determination under the most perilous of circumstances, despite widespread discrimination.

Lt. George Black and Pvt. William “Edward” Black

George Black and William “Edward” Black might just be the most unique father-son duo on this list! During the Civil War, Lt. George Black was commissioned in the 21st Indiana Volunteers. But shockingly, his eight-year-old son, Pvt. William “Edward” Black, joined him in the regiment and served as a drummer boy. It was during the 1862 Battle of Baton Rouge that the young drummer boy was captured by Confederates and imprisoned at Ship Island. In a fortunate turn of events, the Federals overtook the captors and freed the Union prisoners. This led to Edward’s discharge in September 1862.

But he wouldn’t be far from the front for long! By February 1863, he reenlisted with his old regiment, which had been converted into the 1st Indiana Heavy Artillery. It was while serving with the artillery that then-12-year-old Edward became the youngest Civil War soldier injured on active duty, when a shell exploded and shattered his left hand and arm. He remained with the 1st Indiana Heavy Artillery until it was mustered out in January 1866.

Edward’s wartime drum was passed down throughout generations but was gifted to the Indianapolis Children’s Museum in 1970, where it remains in their collections today.

Maj. Gen. Henry Lee III and Gen. Robert E. Lee

The combined military resume between Robert E. Lee and his father, Henry Lee III, proves quite lengthy. At the Revolutionary War’s onset, Henry had already earned a reputation for horsemanship, thus gaining the moniker “Light Horse Harry.” Serving as a major, he took command of a mixed cavalry and infantry corps that went by “Lee’s Legion.” With bold efforts — and a little bit of luck — at Paulus Hook, New Jersey, on August 19, 1779, he performed so ably that he was the only officer under the rank of general to earn the Continental Congress’s Gold Medal. By the Revolution’s end, the elder Lee had attained the rank of lieutenant colonel, although he went on to be promoted to major general in the late 1790s.

Despite a relationship strained by the debts his father had managed to rack up, Robert E. Lee still maintained respect for the father he barely knew — he even paused to visit his father’s grave amidst his inspection of coastal defenses in the winter of 1862. The younger Lee also inherited his father’s knack for military service. After graduating second in his class from West Point, he served 17 years as an officer in the Corps of Engineers and had his first battlefield encounter during the Mexican American War. Distinguishing himself as a part of Gen. Winfield Scott’s staff, the younger Lee earned three brevets for gallantry and emerged from the conflict with the rank of colonel. His highest rank, however, came later – after a stint as commandant of West Point and, ultimately resigning his commission in the U.S. Army – as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, the most famous and successful of the Confederate armies.