Initially you might wonder how “The Bard of Avon” — William Shakespeare (ca. 1564-1616) — possibly has a place in Civil War history. But once you consider the popularity of his works and their influence on American society, you’ll instead be wondering “How could he NOT?” So, as we mark the anniversary of the Bard’s death on April 23 (also possibly his birthday, although records are less certain; we know he was baptized on April 26), let’s reflect on those connections.

Shakespeare’s influence in this country begins in colonial times, with the first documented American performance dating to a 1750 staging of Richard III. During the Revolution, his plays lent the Patriots and the British a common popular language. In Corpus Christi, Texas — during the Mexican American War — soldiers that would later make a name for themselves in the Civil War, were cast in a U.S. Army production of Othello in 1846. While the 6-foot-tall James Longstreet was originally cast to play Desdemona in the production, it was decided that he was too big to play the female character, opening the door for the 5’6”, 135-lb. Ulysses S. Grant to take his place.

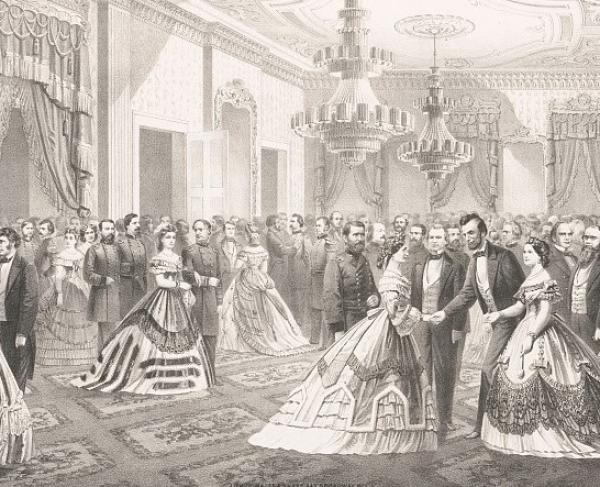

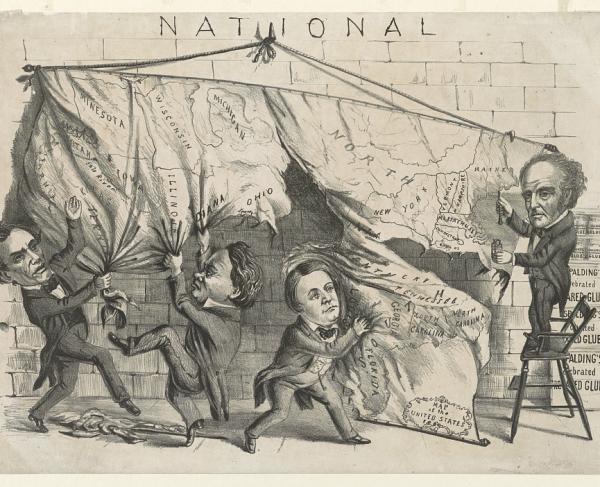

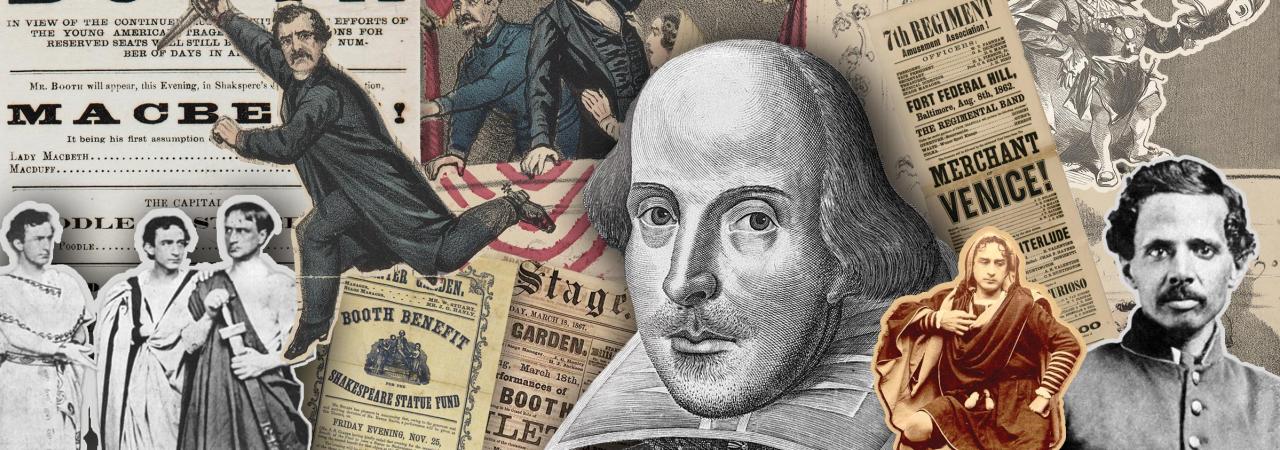

Soldiers in camp and actors on stage would continue to perform Shakespeare’s works during the Civil War, and its influence knew no bounds — being popular in both the North and the South. As a Chicago newspaperman Elias Colbert said in 1864, “It is of the heart that Shakespeare speaks,” and his heart-drawn words were borrowed by not only soldiers and actors, but also cartoonists, writers, and President Lincoln himself, to emote the chaos of the world around them. And what’s more fascinating is how this era of American history was recorded like none other before, through new media like photography and chromolithography. Images of Shakespearian actors in costume, broadsides and posters bringing Shakespeare’s words to audiences far and wide, and American celebrations of the Bard’s 300th birthday… all coincided with the Civil War.

The Link Between Lincoln’s Favorite Play and His Undoing

Before he took on the role of president, Abraham Lincoln would look to Shakespeare when he was a young lawyer traveling from town to town. He was even said to have kept a copy of Macbeth in his back pocket and quoted from it quite constantly. And if you still weren’t sure that Macbeth was his favorite, he says in an 1863 letter to actor James Hackett, “Some of Shakespeare’s plays I have never read, while others I have gone over perhaps as frequently as any unprofessional reader. Among the latter are Lear, Richard Third, Henry Eighth, Hamlet, and especially Macbeth. I think nothing equals Macbeth — It is wonderful.”

And how ironic it was that Lincoln’s demise would come at the hands of a Shakespearean actor, John Wilkes Booth, famed for playing Macbeth himself.

In the wake of the assassination, people across the nation ached at the loss of the great leader and searched for ways to express their grief. Yet again, folks turned to Shakespeare to find words fit to describe the tragedy. On broadsides, a sketch of the shooting could be found coupled with a quote from Macbeth:

“Hath borne his faculties so meek; has been

So clear in his great office; that his virtues

Shall plead, trumped-tongued, against

The deep damnation of his taking off.”

(Act 1, Scene 7)

The lines come from Macbeth, as the eponymous character is praising King Duncan for being a virtuous leader whose legacy will not be contained to his time on earth… all the while plotting to murder said king! Americans looked to King Duncan’s assassination and drew a clear connection to the real atrocity before their eyes.

On the Run with Shakespeare

And it wasn’t only those mourning Lincoln that found comfort in Shakespeare — but also the man who struck him down. After assassinating the president, John Wilkes Booth was on the run for nearly two weeks. Time was ticking as the authorities inched closer and closer, and on April 22, 1865, he took to the pages of his diary with one last entry.

In the entry he thinks about Julius Caesar’s Brutus. “I am here in despair. And why; for doing what Brutus was honored for…” He acknowledges his status as a criminal and recognizes that his end is near. And he finished his entry with a work of Shakespeare’s that he knew unquestionably well after playing the title character in 1863 — of course, it was Macbeth: “but ‘I must fight the course.’ Tis all that’s left me.”

The Booths: A Family of Shakespearean Actors

John Wilkes Booth is widely remembered today, but in the nineteenth century, his brother Edwin was the one who enjoyed the most stardom. The pair, along with brother Junius Brutus Jr., and father Junius Brutus, were all Shakespearean actors. As such, the brothers were constant rivals on stage — with Edwin’s popularity standing above them all. Edwin played the title characters Macbeth and Hamlet, the latter being such an adored part that he played it in 100 shows at Broadway’s Winter Garden Theatre.

In 1864, upon Shakespeare’s 300th birthday, Edwin was part of a group of actors and theatre managers that successfully advocated for a statue of the Bard to be erected in New York’s Central Park. The cornerstone was placed between two elms in the park, but work would need to be done to raise the necessary funds to bring the statue to fruition. And so, later that year, the Booth brothers — in a rare event — joined together in a production of Julius Caesar to fundraise on the statue. But the finished statue of Shakespeare wouldn’t make its true debut until its dedication in 1872.

One of 25 Black Medal of Honor Recipients From the Civil War, Powhatan Beaty Became a Hit Performing Shakespeare

Powhatan Beaty served in the 5th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment during the Civil War and for his jaw-dropping bravery at the Battle of New Market Heights, he received the Medal of Honor.

Following the war, Beaty returned to his hometown of Cincinnati, married, and settled back into cabinet making. However, he found greater fame through his love of theatre; by the mid-1880s Beatty had connected with prominent African American Shakespearean actress Henrietta Vinton Davis. Together, they put on a large musical and dramatic festival, featuring selected scenes from Macbeth, with the pair in the leading roles. They even took to the road and put on performances for packed houses.

In Philadelphia, he was noted as “a gentleman of rare culture and great ability,” while The Washington Bee said that “Mr. Beaty made a hit in Macbeth.” And while not related to a work of Shakespeare, the New York Globe’s review of his performance as Spartacus couldn’t have been any better:

“Powerfully built, rugged and strong in his general appearance, he looked every inch a Roman gladiator. The audience leaned forward and eagerly listened to catch every word of his impassioned delivery, and when he finished they fell back in their seats with a sigh of relief that plainly expressed how they had been affected. Mr. Beaty is indeed a grand artist and has wisely selected the tragic muse for the shrine of his artistic devotion.”

Frederick Douglass: Big Fan of the Bard

After performing in Philadelphia and Washington, Powhatan Beaty was invited to a dinner held for renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Not only a fan of Beaty’s acting chops after seeing him in Washington, D.C., Douglass was also well aware of Beaty’s wartime bravery.

In addition to his work to advance social justice, Douglass was a philanthropic patron of the arts, and used his many connections in Washington to grow the careers of Black artists. He was also a fan of William Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s works did not only have a place in his library — they would furthermore make appearances in his speeches and he would frequently attend performances of Shakespeare at local D.C. theatres. He even participated in the Uniontown Shakespeare Club’s readings at least twice. In a letter dated December 1877, Douglass wrote about participating in a reading with the club… “The play was the Merchant of Venice and my part Shylock.”

Shakespeare has inspired and confounded for hundreds of years, but his words found an added layer of complexity when mixed with the drear conflict of the Civil War. As many were familiar with his work, Shakespeare became a comfort in camp, a source through which one could better express love or tragedy, a reminder of reality versus fiction, and a path that allowed a handful to live out — or act out — their dreams.

“Come what come may,

Time and the hour runs through the roughest day.”

Macbeth (Act 1, Scene 3)