Once the scene of fierce combat, the Peach Orchard lives on today through efforts in 2008 to replant 72 peach trees.

The Peach Orchard at Gettysburg is critical ground, albeit frequently overlooked.

Visitors to the southern part of the park are drawn to Devil’s Den and Little Round Top — the rocky hill is a must-stop for its panoramic views. Kids love the Den’s immense boulders. As the park evolved, these sites have gotten the most emphasis in preservation, interpretation and tourism.

But in the actual battle, the Peach Orchard position was as important — many would say more important — as these other locations for two reasons.

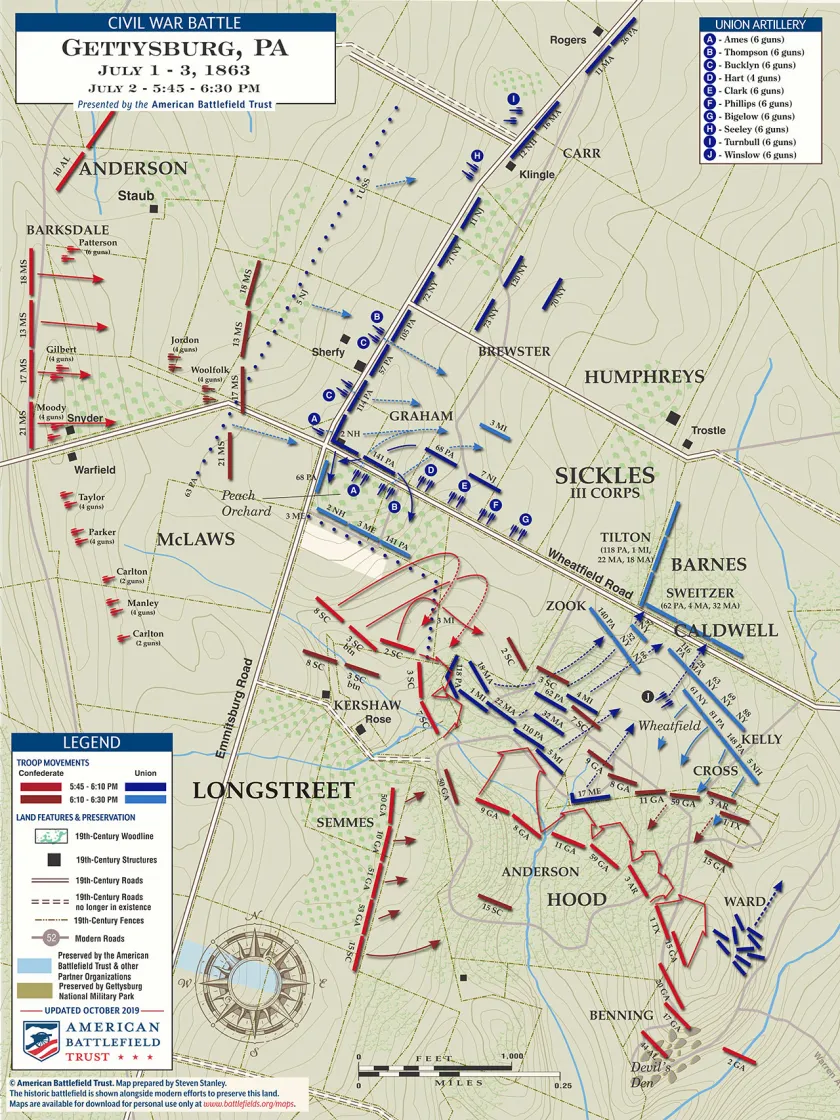

First: The Emmitsburg Road, running south to north, was used by a third of the Union army to get to the battlefield. The Millerstown Road (aka Wheatfield Road), running west to east, was the main access route on July 2 for the Army of Northern Virginia to get at the Union army’s left flank. The importance of this intersection cannot be overstated. And right at this intersection stands the dense, four-acre Peach Orchard, providing concealment and cover.

Second: The Emmitsburg Road sits on a small ridge running north about a quarter mile toward town. The Peach Orchard sits on the highest point of this ridge. It is the high ground between the opposing forces.

The height of the Peach Orchard means Union forces by the Trostle Farm could not see beyond it. Confederates deploying on Warfield Ridge were out of sight. Likewise, Confederate officers could not look beyond the Peach Orchard to see what might be coming up. At one point, the commander of the attacking force, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, walked with one of his brigades out to the Emmitsburg Road to see what was happening on the other side.

For these reasons, the Peach Orchard became a center-point of the fighting on July 2 — the largest and bloodiest day of the battle.

It was a site of surprises. For one, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee chose the intersection at the Peach Orchard as the launching point for his attack. Union commanders had expected it elsewhere.

Before Lee’s troops arrived, Union Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles moved his III Corps up to the Peach Orchard. This surprised Lee and Longstreet inasmuch as Sickles’ move also surprised the Union army commander, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade.

The first combat at the Peach Orchard was an artillery fight without precedent. As many as 86 guns exchanged close-range fire while the infantry prepared for action. One New Jersey battery fired 1,342 shots, a record for the Civil War. Confederate Col. E. Porter Alexander called it the hottest, sharpest artillery fighting of the war.

The infantry attack followed. New Hampshire men faced off against South Carolina men, only to change fronts to face a new attack from Mississippi forces. As the Union position caved, the 141st Pennsylvania struggled to hold their line and protect their guns. They numbered just 209 men at the outset and lost 149 of them.

The Confederates did break the Peach Orchard position. And they held it the next day as an artillery platform to support Pickett’s Charge. Lee in his battle report for July 2 claimed that getting “a position from which it was thought that our artillery could be brought to bear with effect” was his objective of the day. It rings false, but it is what he wrote.

We're on the verge of a moment that will define the future of battlefield preservation. With your help, we can save over 1,000 acres of critical Civil...

Related Battles

23,049

28,063