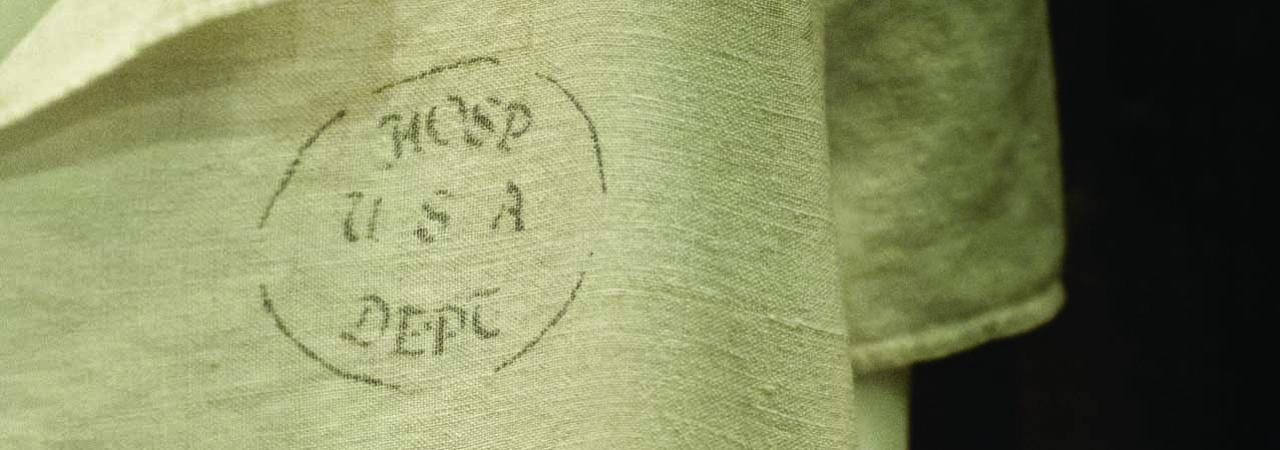

Hospital shirt in collection of National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Frederick, Md.

When most people think of Civil War medical practices, they envision brutal amputations carried out by exhausted surgeons without the use of anesthesia, and dark, dank hospitals where wounded and sick soldiers were sent to die slow, agonizing deaths.

It’s true that Civil War surgeons did not have a complete understanding of germs and microbes and generally did not use antiseptics to prevent infection, but the story of wartime medicine is far more complex. The use of opiates for pain, the almost-universal use of anesthesia during surgeries, the availability of medicines like quinine and bromine and the training level of the surgeons all contributed to surprisingly effective medical care during the conflict.

Tremendous strides were made during the Civil War and in subsequent conflicts to medical procedures and techniques that still impact our lives today. Every time you see a speeding ambulance staffed with EMTs, thank the military medicine of the 1860s!

The Medical Response

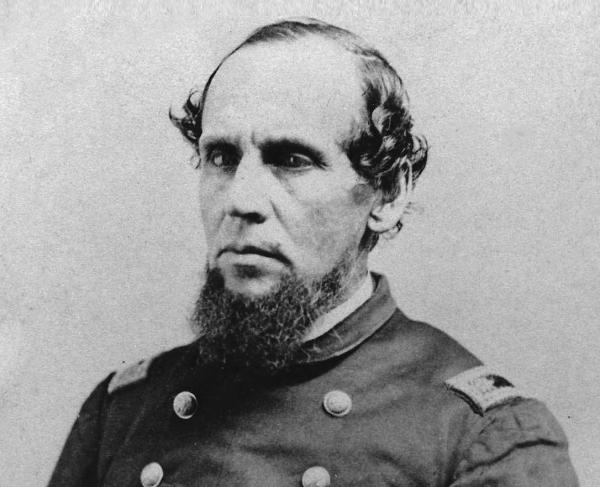

After the July 21, 1861, First Battle of Bull Run, hundreds of casualties lay suffering on the battlefield, some for up to a week, because there was no system in place to quickly remove them to care facilities. The public outcry over that misery prompted Abraham Lincoln’s administration to place William Hammond as surgeon general, and he in turn appointed his prewar friend and associate Jonathan Letterman as medical director of the Army of the Potomac in June 1862. Both men realized a better system was needed to evacuate wounded soldiers from the battlefield.

Letterman saw that disorganization and fragmentation in the medical response process was costing hundreds of lives and issued a series of general orders that better organized camps for sanitation and brought about a new system for the removal of wounded from the battlefield to hospitals and for their general care.

The Origins of Triage

Although “triage” was not used as a medical term until World War I, its fundamentals were instituted in the Civil War. The first stop on the Letterman Plan was the field dressing station, located as close to the battlefield as possible. Here, surgeons, hospital stewards and other caregivers administered first aid and sorted casualties according to the seriousness of their wounds. Patients were grouped using the following criteria: slight, mild, severe and mortal.

Slight wounds were minor injuries that could be treated, and the patients then sent back to their units. Mild wounds included excessive bleeding with the patient in stable condition and were evacuated after all the severely wounded were removed from the battlefield. Severe wounds included serious bleeding, compound fractures, missing limbs or major trauma to the arms and legs. These were taken by ambulance to the nearest field hospital for immediate care.

Mortal wounds were the lowest priority and included injuries to the trunk of the body or the head. These patients would have been given morphine for pain, made as comfortable as possible and set aside until there was time to return to them. This was not due to cruelty on the part of the surgeons — they simply lacked the knowledge and technology to treat these kinds of wounds. Before antibiotics or germ theory, abdominal surgery was rarely attempted since there were almost always fatal complications.

Modern triage, established with a color-coded system, closely mirrors its Civil War counterpart and is based on the principle of doing the greatest good for the greatest number with the available resources. While it is practiced throughout medicine by first responders and emergency room personnel, we usually think of triage in terms of mass-casualty incidents, or incidents in which the number of casualties overwhelms medical personnel and resources.

In these instances, it is ideally performed rapidly, with 15–60 seconds spent on each patient, who is then categorized according to the universal colors of red, yellow, green and black. Red (immediate) patients are the first priority and include pneumothorax (collapsed lung), hemorrhagic shock (significant blood loss), closed head injury and diminished mental capacity (unable to follow simple commands).

Yellow (delayed) patients have major or multiple bone, joint, back or spine injuries with an unobstructed airway. Those placed in the green (minor) category are the “walking wounded” — individuals who can follow commands but have minor cuts, bruises, painful and swollen deformities or minor soft tissue injuries. The lowest priority is given to those who fall into the black (deceased) category.

These include obvious mortality or death, including decapitation, blunt traumatic cardiac arrest (no pulse or spontaneous respiration), injuries incompatible with life and visible brain matter. Keep in mind that triage is an ongoing process performed continuously throughout the primary assessment, treatment, transportation and hospital phases of care.

While medical care and knowledge of physiology have far surpassed that of the 19th century, triage categories remain largely unchanged since the Civil War. Our modern red, yellow, green and black triage parlance all closely mirrors the Civil War–era categories of severe, mild, slight and mortal wounds. In both instances severe, or red, are given first priority; mild, or yellow, are treated next; green, or slightly, third; and very last are the black, or mortally, wounded.

Ambulances and Hospitals

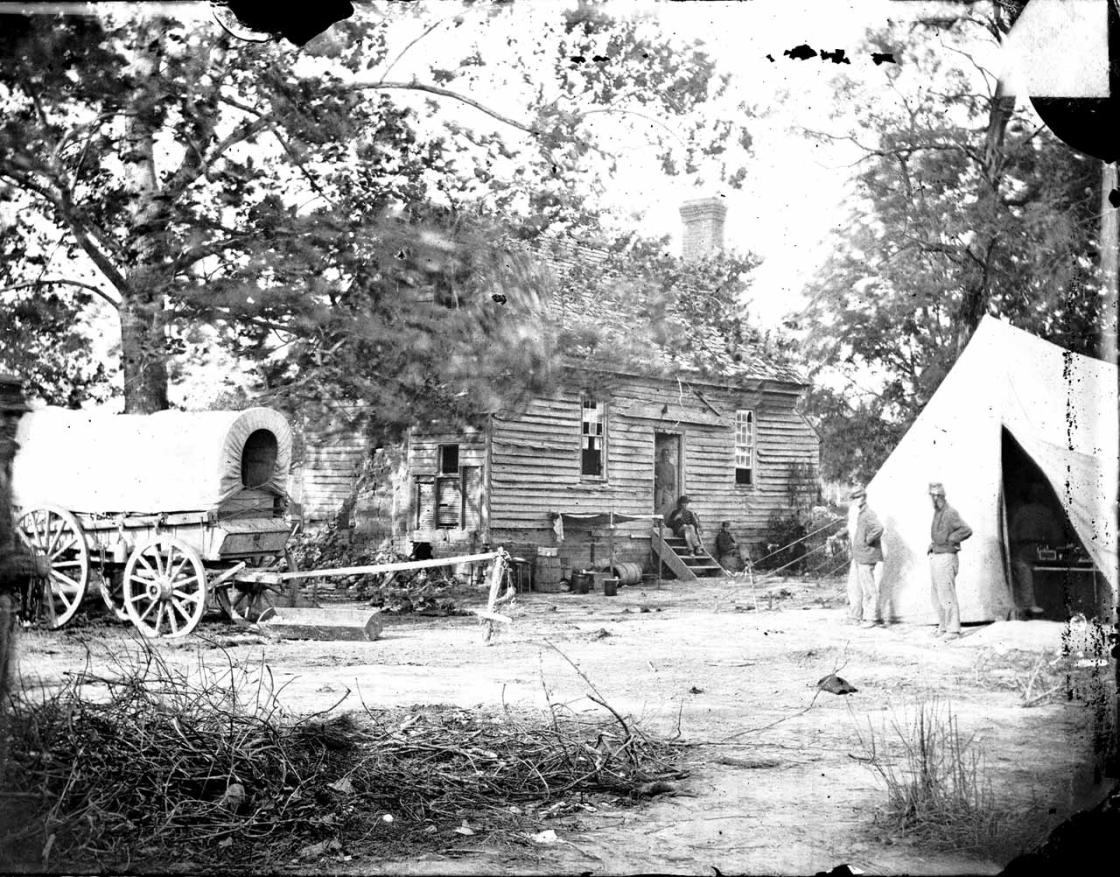

After injured soldiers had received this initial treatment, they were then sent on to semi-permanent field hospitals in barns or large houses. Trained stretcher bearers and a formalized ambulance corps transported the injured off to these field hospitals located in the rear, where most amputations occurred. It is estimated that about 60,000 amputations were performed during the war, and anesthesia was used in about 95 percent of these operations.

The final stage of Letterman’s plan called for the wounded to be transported farther from the battlefield to larger brigade or general hospitals in nearby towns. Ambulances, trains and steamer ships were all used to move large numbers of injured soldiers to such hospitals for further care and convalescence. If a patient reached a general hospital, they had a 92 percent chance of surviving.

Letterman’s system for the evacuation of the wounded was first put into use after the Battle of Antietam, and the vast majority of wounded were off the battlefield within 24 hours. Of course, the system did not operate perfectly, and there were peaks and valleys in its execution. But the reforms instituted by the “Father of Battlefield Medicine,” as Letterman became known, dramatically increased survival rates. By February 1864, the Letterman Plan had become the official medical response for the U.S. Army, and the Confederate Army adopted a similar plan. The modern U.S. military still uses Letterman’s plan as its framework for wounded care.

Long Term Convalescence

Prior to the Civil War, few Americans saw the inside of a hospital. People were born at home, and most died there. Doctors made house calls, or the ill might visit a small, local doctor’s office. Hospitals were considered a place of last resort — where the indigent went when they had no other options. The Civil War changed that mindset. When the conflict began, the U.S. Army only had one 40-bed hospital in Kansas, but the massive number of injuries forced the establishment of large-scale hospitals, which had an astounding average survival rate of more than 90 percent. Success and familiarity meant that postwar hospitals were seen as places of healing rather desperation.

Both Union and Confederate surgeon generals were inspired by the European pavilion hospital designs also favored by the famous British nurse Florence Nightingale. A pavilion hospital featured long, narrow wards with multiple windows to promote cross-ventilation. Attention was also paid to the location of heat sources, how patent beds were placed and even how much space should be devoted to each patient for the best care. Built in October 1861, Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, Virginia, was the first American facility to use this plan; its 150 pavilions and 4,000 beds making it the Confederacy’s largest hospital. When Satterlee, or West Philadelphia U.S. General Hospital, followed in June 1862, it held 3,500 beds in the pavilion style, plus 150 tents around the building for overflow in the event of an emergency or nearby engagement.

The Civil War can also be credited with the introduction of women into the medical sphere. Before the war, nursing was considered a man’s job, and too “intimate” a profession for women. But the massive scale of injury brought on by the war prompted thousands of female nurses like Clara Barton, and Dorothea Dix and Susie King Taylor (USCT) to leave their homes to succor the wounded and sick. It’s estimated that 20 percent of the nurses on both sides were women by the end of the war. Although there was a great deal of prejudice against them, especially early on, surgeons came to value that their contributions and nursing as a true profession was born.

Dorothea Lynde Dix was born on April 4, 1802, in Hampden, Maine. As a young child, Dorothea moved to Worchester, Massachusetts, to live with her...

Born into slavery in Georgia in 1848, Susie King Taylor (born Susan Baker) lived on a plantation for the first seven years of her life. In 1855, Susie...

The sheer number, severity and variety of wounds that medical professionals encountered during the Civil War saw specialization became more commonplace, as great strides were made in orthopedic medicine, plastic surgery, neurosurgery and prosthetics. Specialized hospitals were established, the most famous of which was set up in Atlanta, Georgia, by Dr. James Baxter Bean for treating maxillofacial injuries. Nerve injuries were treated at a specialty hospital in Philadelphia called Turner’s Lane, paving the way for the establishment of the disciple of neurology. Drs. Silas Weir Mitchell, George Read Morehouse and William W. Keen were early practitioners of this specialty.

Conclusion

Medical technology and scientific knowledge have changed dramatically since the Civil War, but the basic principles of military health care remain the same. Location of medical personnel near the action, rapid evacuation of the wounded and the provision of adequate supplies of medicines and equipment continue to be crucial in the goal of saving soldiers’ lives. Civilian health care, especially in the areas of emergency response and mass-casualty situations, often follows the principles and practices first developed in the military. As has been the case throughout history, the lessons learned, and the technical developments made by the military rapidly find their way into civilian applications. To this end, these medical breakthroughs eventually benefit all of society.