When Henry Barnum enlisted in the 12th New York Infantry in 1861, he no doubt considered it was a very real possibility that he might never return to his wife and infant son at their Syracuse, New York, home. And for a few weeks in the summer of 1862, it looked like that worst-case scenario had become reality.

While serving in the Peninsula Campaign, Captain Barnum was shot in the front of his left hip at the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862. The ball slammed through the front of Barnum’s hip bone and passed out through his back. He stayed on his feet for a moment or two, remaining in command of his men until he collapsed from blood loss. Barnum was taken to a field hospital, but as abdominal wounds were often regarded as a death sentence, the surgeons considered his wounds fatal, and his name was listed on the rolls of the dead. At home in Syracuse, eulogies were read. Family friends, working on behalf of Barnum’s young wife Lievina, wrote desperate letters to the front lines, hoping to secure the officer’s body for return home for burial.

But what his Syracuse friends could not know in those hot, agonizing days of early July was that Henry Barnum was not dead. Although Federal surgeons declared him a fatal case at a glance, Barnum was later discovered by Confederate forces and taken prisoner. He spent several days in a Confederate field hospital, then was taken by wagon to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, where he stayed until mid-July, when he was released in a prisoner exchange. From there, he was transported by hospital ship to Albany, New York, then, finally, home to Syracuse by rail. Incredibly, through all these weeks of imprisonment and travel, Barnum remained medically stable, with no signs of serious infection.

That fall, after a few weeks convalescing at home, Barnum returned to Albany for a more thorough medical inspection of the wound. The entrance wound was widened, and physicians explored and cleaned it, removing chunks of splintered bone and fitting Barnum with a tent, a kind of soft fabric plug that kept the wound open and draining. After some weeks, Barnum removed the tent and allowed the entrance wound to close. Never daunted, while recuperating at home from this serious war wound, Henry Barnum and Lievina conceived another son, named for the battle that nearly took his father’s life: Malvern Hill Barnum.

For many, a wound like Barnum’s would have felt like sufficient sacrifice, more than justifying the decision to accept a disability discharge to remain safely at home to recuperate. But Barnum was not done fighting. He re-entered the Federal army in January 1863, took command of the 149th New York and was eventually promoted to brigadier general. Barnum’s story is not typical. Most soldiers wounded so severely died — whether of infection, blood loss or shock. For those who survived, encounters with medical care were shaped by status. Most enlisted men didn’t have access to elite medical care, couldn’t afford to travel for care or couldn’t access the extended medical leaves afforded to officers. However singular in its details, Barnum’s harrowing experience is a powerful testament to an underappreciated reality of Civil War wounds: They did not disappear with the cessation of fighting, nor did heroism lessen their lasting effects. Barnum returned to the army, went on to a successful political career and was lauded for his heroism with a Congressional Medal of Honor. None of this could stop the pain, chronic illness or eventual fatal effects of Barnum’s never-healing wound.

Barnum’s grit was inspiring — but no amount of determination to return to the front lines could forestall the lasting effects of such profound bodily trauma. Just months after he returned to the field, he developed an abscess that burst, reopening the wound. He took medical leave, and a surgeon removed more dead bone and fit the wound with another tent. Barnum returned to the field in late spring and served through the Gettysburg Campaign, but pain, weakness and infection forced him to take another leave shortly thereafter. That fall, though hardly able to walk, he led his men into battle at Lookout Mountain — until he was shot again, this time in his right forearm.

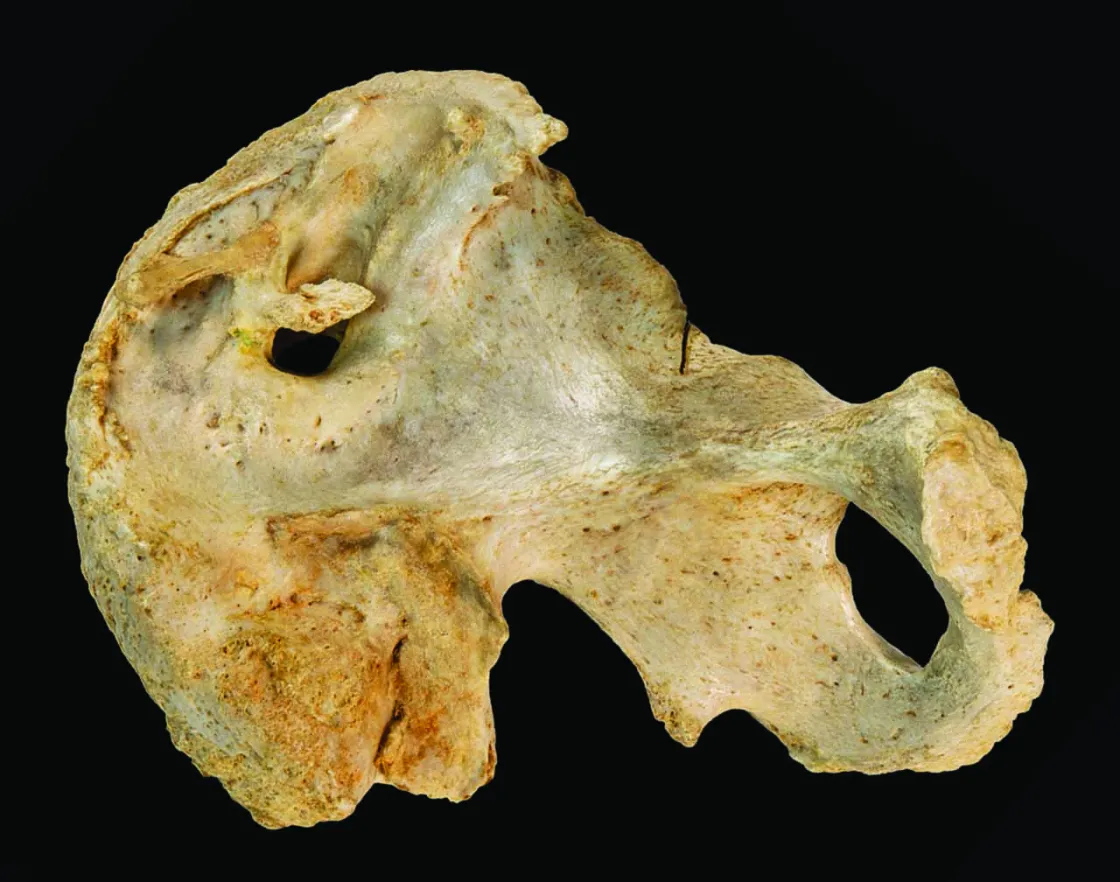

When another abscess formed on his hip wound in the winter of 1864, Barnum sought treatment from Dr. Lewis D. Sayre, a pioneer in osteopathic surgery. Sayre discovered that the original path of the bullet, which passed through Barnum’s ilium, had become a pocket of infection in his bone. Sayre reopened the healed exit wound, releasing the trapped infection and determined that the only way to preserve Barnum’s life was to leave the wound open and draining. Sayre fitted Barnum with an oakum string tied in a loop through the wound. The oakum was eventually replaced by long pieces of candlewick, which Barnum wore, threaded through the open wound, for the remainder of his life. Still, he returned, eventually, to the fighting, and in the final year of the war received two more wounds, one at Kennesaw Mountain and another at Peach Tree Creek.

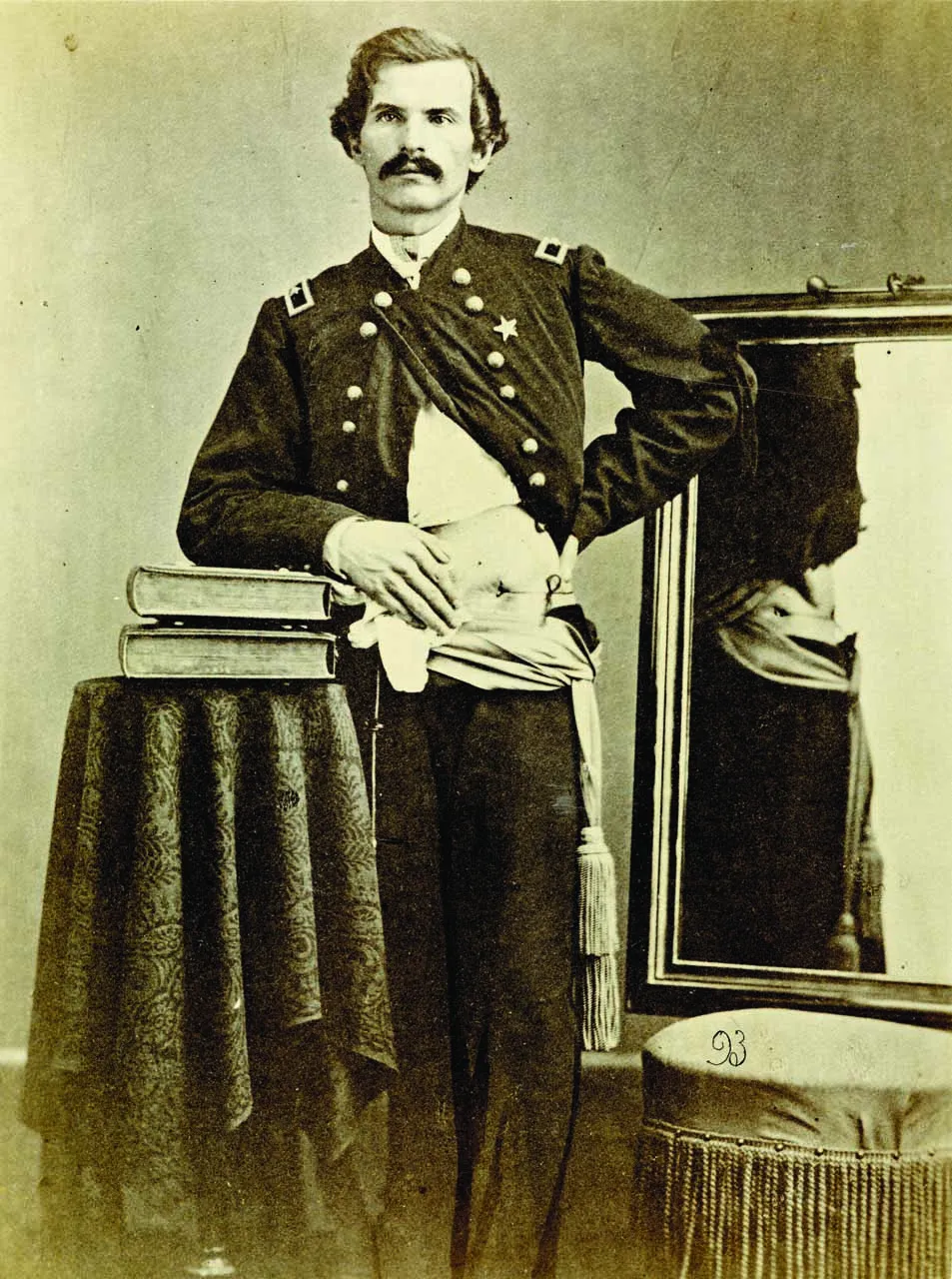

After the war, Barnum’s hip wound became famous. Dr. George Otis, curator of the Army Medical Museum, which was established during the war by the Surgeon General’s Office, requested that Major Barnum’s wound be photographed for inclusion in its opus on the wounds and diseases of the war, The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865. Barnum was photographed at the museum in Washington, D.C., in 1865. The photograph was also displayed in the museum. Barnum even used the photograph to lend credibility to his pension application in 1866.

Barnum was photographed throughout his life; sometimes submitting new images to the Pension Bureau to add to his file. Barnum’s pension file includes an additional photograph, for instance, that shows the much older general still wearing a military uniform. He signed the photograph, his signature scrawled beneath the line of what appears to be either a rope or rod passing through his still-open hip wound. He also had private photographs taken, likely back home in Syracuse, wearing civilian clothing. At a time when conservative politicians claimed the pension system was riddled with fraud, Barnum was able to use photographic evidence of his wound to prove its continuing impact, an effort rewarded with a special act of Congress that raised his pension to $100 a month.

In his postwar life, while serving in political positions in New York State, Barnum also had a role as a living medical specimen. He was summoned to Washington, D.C. in 1881 so that his body could serve as an example to the surgeons caring for President James Garfield, who lay suffering from an assassin’s bullet. The Syracuse Courier reported in July 1881 that “General H. A. Barnum, who for nineteen years has carried an open bullet wound through the body … and is now wearing a rubber draining tube through the track of the ball, passing through the left ilium, was this morning telegraphed to go to Washington for personal examination by the President’s surgeons, with a view of such information as his care may give with reference to the President’s wound.” Not only was Barnum’s wound publicized, it continued to do a service to the nation by offering its painful lessons to the surgeons attending the gravely wounded president.

To the nation’s medical elite, Barnum’s wound was extraordinary, a rare specimen with potential for medical knowledge. But for Barnum, the wound was also the cause of chronic illness, pain and infection. He returned repeatedly to Dr. Sayre, who eagerly probed it, clearing out new bits of dead bone and introducing new drainage methods. Barnum lived with discharge and bleeding from the open wound, and his incurable osteomyelitis occasionally erupted into bouts of septicemia.

In 1892, Barnum died at the age of 58 from pneumonia — though his body’s susceptibility to infection must have been shaped by years of the pain, illness and stress that came as consequences of his war wound. Even in death, Barnum was a useful medical specimen: He left his left hip bone to the Army Medical Museum, where it remains to this day. Modern CT scans of the bone have shown that it was riddled with lead fragments left by the bullet that smashed through it in 1862. Without antibiotics or advanced imaging, even the elite Dr. Sayre would not have been able to cure Barnum’s never-ending infection.

For many Americans, the Civil War stands apart as a uniquely valorous and important war, a moment when the nation’s central principles were tested and reinforced. But like all wars, the Civil War was destructive, gouging landscapes, ruining cities and mangling human bodies. While Henry Barnum’s decades-long experience was in many ways rare, it was also an extreme example of an experience shared by veterans across the postwar United States, left to grapple with the long-lasting effects of wounds large and small, physical and invisible, the inevitable byproducts of all armed conflict.