“I have never spared the Spade and Pick Ax”: Fortifications in the American Revolution

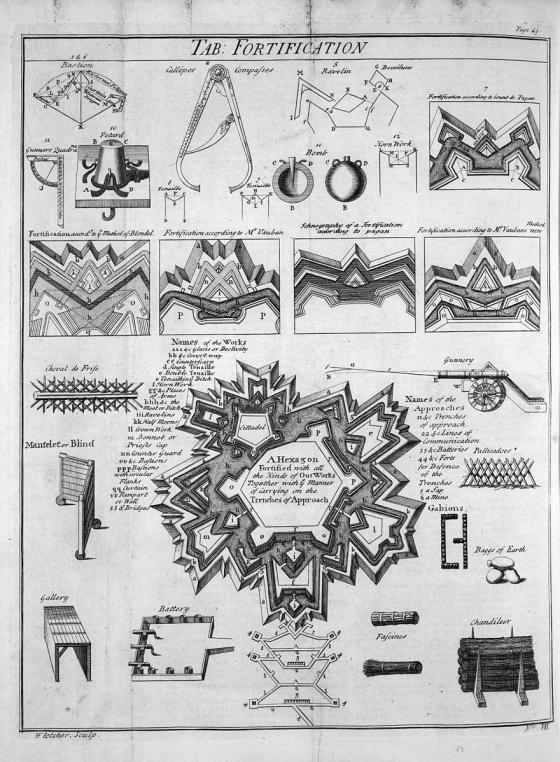

In the centuries after the introduction of gunpowder, the construction and use of military fortifications underwent a radical transformation. Artillery and firearms rendered the high walled stone castles of the medieval age obsolete. Forts took on geometric shapes, with bastions that provided overlapping fields of fire. High, straight-sided walls were replaced by lower, sloping walls to absorb or deflect artillery fire. A whole new vocabulary of military engineering evolved, with works like redoubts, redans, couvrefaces, ravelins, lunettes, and others.

Military Engineering

Much of this advancement in the military science of engineering occurred in France during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The most influential engineer of the era was Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707). Born to a minor noble family, in his youth he excelled at mathematics and geometry. This would serve him well as he began a military career and he soon gained a reputation as a skilled engineer. He revolutionized siege warfare with his refinement of “offensive” works of parallel trenches that would shield the attackers when attacking enemy forts. He also worked to perfect the science of defensive fortifications, creating bastioned “start forts” of increasing geometric complexity. His military theories were published and widely read, and his works would dominate European military engineering for the next 150 years. The engineers of the American Revolution, whether British, American, French, or otherwise, were all deeply rooted in the works and theories of Vauban and his contemporaries.

When the Revolutionary War began, there were few professional engineers in the British colonies, and the lack of trained engineers would plague both armies throughout the war. In 1775, only six of the sixty-one officers of the British Corps of Engineers were stationed in North America, and most were in Canada or Florida. Through the early years of the war, Captain John Montresor (1736-1799) was the principal British engineer in America, and would serve through the Siege of Boston, the battles around New York, and the campaigns in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

The American forces had no professionally trained engineers at the start of the conflict, and would rely greatly on foreign volunteers to build up an effective engineering corps. Louis Duportail (1743-1802), a graduate of the French engineering school, arrived in America in March 1777 and soon proved indispensable. As chief engineer of the Continental Army, he oversaw the construction of fortifications from Massachusetts to the Carolinas and was largely responsible for the siege works at Yorktown. Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817) came to America from Poland and volunteered his services in the summer of 1776. His engineering skills were quickly recognized, and during the early years of the war, he designed several fortifications around New York. He is most remembered for designing the fort at West Point, which would go on to be the site of the United States Military Academy.

The actual construction of fortifications often fell to the soldiers themselves. Within the British military, there were specialized “pioneers” who were skilled at carpentry, masonry, and other construction trades. There were also organizations raised from local loyalists, like the Corps of Guides and Pioneers, and they often employed the labor of liberated slaves for construction. Within the Continental Army, specialized companies of “Sappers and Miners” were raised to assist with the creation of field fortifications.

Fortifications

The fortifications used during the American Revolution can be broadly categorized into two classes: permanent fortifications and field fortifications. The former refers to large, fixed fortifications, typically built during peacetime. These fortresses were constructed to protect strategic locations such as important cities or harbors. Field fortifications, on the other hand, were temporary structures built by the armies in response to enemy movements or perceived threats. Although permanent and field fortifications differed in construction and scale, they served the same purpose and usually relied on the same geometric principles. Both would play a pivotal role in the American Revolution.

Permanent Fortifications

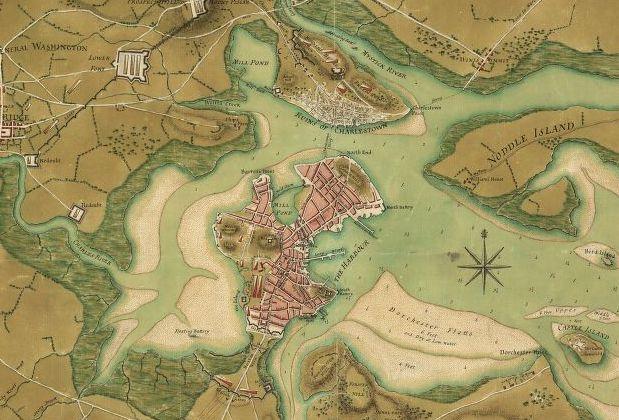

When the war began, there were relatively few permanent forts in North America. In the past, most American wars were fought against Native Americans who lacked the artillery needed for siege warfare. The lack of good roads and infrastructure in the interior of the continent also limited the use of siege artillery. As a result, most forts used on the frontier were often little more than wooden stockades or blockhouses. Larger permanent fortifications were usually limited to areas where attacks from other European powers were expected, such as the ports and cities on the coasts and along major waterways. Cities like New York, Boston, and Charleston featured forts and batteries to protect them from attack by sea. Large forts also occupied military posts around the edges of the British colonies, like those at Halifax and Pensacola.

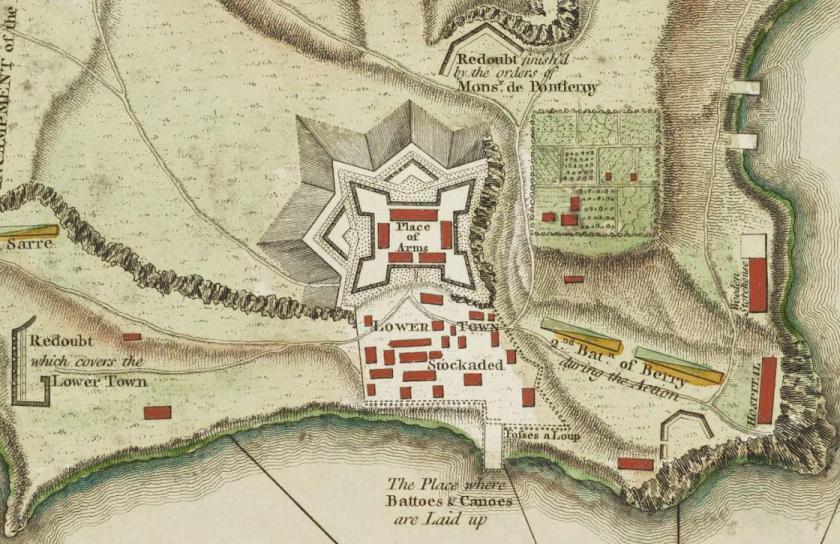

One of the most impressive examples of permanent fortifications in 18th century North America was the city of Quebec. Since the first French settlements in the early 17th century, the high land above the St. Lawrence River had been built up with a successive number of forts. By the mid-1700s the city was completely enclosed by a series of stone walls, complete with bastions and artillery batteries, that protected it from attack by both land and sea. The walls played a crucial role in the December 31, 1775, American assault on the city. The intricate system of gates, walls, and bastions proved essential in slowing down the American attack and allowing the British defenders time to mount an effective resistance.

The most famous example of permanent fortifications in the Revolutionary War is Fort Ticonderoga. Originally built by the French in the 1750s, the massive stone star fort guarded the Lake Champlain corridor between Canada and New York. Despite its imposing walls, the fort would be captured twice during the Revolutionary War. The first capture occurred on May 10, 1775, when a force led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold surprised the tiny British garrison. The British later recaptured the fort in 1777 as General Burgoyne’s army marched south during the Saratoga campaign. Burgoyne’s forces were able to drive the Americans from the fort by placing artillery on the high mountains around Ticonderoga, threatening the fort with plunging artillery fire.

Field Fortifications

Field fortifications saw much wider use during the American Revolution. These could range in complexity from simple breastworks of earth or logs thrown up just before a battle, to more extensive networks of trenches and protective emplacements. Officers on both sides were quick to take advantage of the protection offered by field fortifications. George Washington, in particular, realized that the disadvantage in the quality of his troops could be offset by a good defensive position. In the summer of 1776, as his men busily fortified New York, he wrote to Congress that, “I have never spared the Spade and Pick Ax.”

The most common styles of field fortifications during the war were redoubts and redans. A redoubt was a small, self-contained fort consisting of a wall, ditch, and other obstacles like abatis or sharpened stakes (fraise). Redans were a similar shape but were open to the rear. The New England militia famously occupied a redoubt on Breeds Hill, inflicting terrible casualties on the British from their protected position. American field fortifications also played an important role in the battles around New York City. The following year, British and German troops used a series of redoubts to blunt American attacks at the Battle of Saratoga.

The best example of field fortifications during the war was erected during the Siege of Yorktown. Crown forces erected a complex line of bastioned works surrounding the town, with additional redoubts and outer works to protect against the approaching allies. Their French and American opponents countered by digging a series of parallel trenches, according to the method described by Vauban. These offensive works allowed the allies to approach within assault range of the British outer defenses, setting the stage for the successful Franco-American assaults on Redoubts 9 and 10. Loss of their outer works left the remaining British entrenchments exposed, leading directly to the surrender of Cornwallis’s army.

Further Readings

- Forts of the American Revolution By: René Chartrand

- Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown 1781 By: Jerome Greene

- “The British Engineers in America 1755-1783.” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. Vol. 51, No. 207, pp. 155-163. By: Douglas Marshall

- Engineers of Independence By: Paul Walker