An Interview with Historian James McPherson

By Clayton Butler

The Civil War Trust's own Clayton Butler recently had the opportunity to sit down with one the most distinguished scholars in the field of Civil War history – Dr. James McPherson, Princeton University's George Henry Davis 1886 Professor of American History. He shared his thoughts on the state of current Civil War scholarship and the compelling nature of Civil War history for scholars and the general public alike. As Dr. McPherson make clear, the field of Civil War history has only strengthened as it has expanded, and continues to be heir to an extraordinarily rich tradition of first-rate scholarship and research.

Clayon Butler: Do you have a favorite battlefield?

James McPherson: Well, the one I know best and the one I give tours of the most is Gettysburg; in some ways I suppose would be my favorite just because of its importance, and the complicated nature of the battle, which makes it kind of interesting to give tours. If people are aware of any one Civil War battle, it’s Gettysburg, so there’s more awareness, more alertness to it. I’ve given tours of almost every one of them, over time. I suppose Antietam and Shiloh are the two best-preserved battlefields, in terms of what is called ‘historical integrity’ - that is, what the soldiers might have seen. They haven’t changed that much over time, especially Shiloh.

Do you have a favorite that’s maybe more off the beaten path?

JM: Well, I suppose – it’s not really off the beaten track and there’s no park involved, but – Brandy Station. The Trust has been active preserving land there. There are interpretive markers there that the Brandy Station Foundation put down there. I enjoy going there.

I understand that you don’t actually teach anymore.

JM: No, I retired eight years ago. My last PhD student came through the pipeline and finished about five years ago. As long as I was teaching, both undergraduates and graduate seminars, I would keep up with all the literature and the journals and what my students - but also others - were doing. But I’ve kind of drifted away from that the last several years. The one way I do stay on top of what’s going on is that publishers frequently send me the proofs, or the manuscript, of a book and ask for a blurb. So I get a pretty good idea of what’s going on. That includes a lot of non-academic stuff. As I’m sure you know, there’s kind of a bifurcation in the field of Civil War scholarship between academic studies and then the more - I don’t know what you would call it - general audience studies, which tend to be military, whereas the academic studies tend to be more in the area of social and political history or economic history.

I think it’s fair to say that you, in your career, have bridged that gap.

JM: That’s been my mission.

How would you say you’ve been able to accomplish that?

JM: Well, I guess I would quote the instructions I got from C. Vann Woodward, who was the editor of the Oxford History of the U.S. series that Battle Cry of Freedom was a part of. The purpose of that series was to try to bring the latest in professional scholarship to a broad general audience, and that’s what I tried to do in that book. But that wasn’t new to me, I had always thought that that was a kind of duty of historians: if they had the ability to do it, to speak to an audience beyond the academy. I’ve always believed in that purpose. And I tried to do it in that book, and in my other books too.

Is there a narrative out there, that you disagree with, that is frustrating to you because of its prevalence?

JM: In a way, there’s a counter-narrative that annoys me, and that’s the neo-Confederate approach to things. At one time I think that was a dominant thrust in a lot of the historical writing about the Civil War, but I don’t think it really is any more. There are also the sort-of libertarian right, and their vendetta - I guess you might call it - against Lincoln. DiLorenzo is probably the best-known name with that, but the League of the South is associated. There’s a kind of alliance between that organization; one faction of the Sons of Confederate Veterans - they’ve split into two factions – and libertarians that is, I think, very much against the grain of most historical scholarship, but it does annoy me, the - as David Blight calls them - ‘Lincoln haters.’ But that, as I said, I don’t think is dominant.

How would you refute these ‘Lincoln-haters?’

JM: I basically would refute it by saying that Lincoln infringed less on civil liberties than some other American wartime presidents have done, even though the Civil War was a greater crisis in internal security than those wars have been. So, compared to the internment of Japanese-Americans in World War II, or the Sedition & Espionage Acts of World War I, the infringement on civil liberties and the kind of ‘imperial presidency’ – if you will – in Lincoln’s time was really fairly mild. Look what’s going on today, with the National Security Administration! Lincoln never did anything like that. The technology wasn’t there of course, but even so.

What would you consider to be the most significant findings, or theories generated, in the last ten – fifteen years?

JM: Well, I think the focus on social history; the history of communities; the impact of the war on families, on women, on children and the way in which the war projected itself into just about everybody’s life in that era more than probably other wars America has fought. That’s obviously the case in the South but it’s true even in the North as well. And some of the demographic work that’s been done as well on just the impact of massive death, [such as] Drew Faust’s book, which has gotten a lot of play through the Ric Burns television presentation. I think what you might call social and demographic history has been probably the most interesting and important new stuff that’s come out in the last twenty years or so.

What is your evaluation of the sesquicentennial commemorations so far?

JM: What I’ve seen of it has been fairly positive, I think. Virginia as a state, I think, is doing more than any other. I was on one [panel] at Norfolk a couple years ago, on the impact of the war on African-Americans. And I thought it was really quite good. I was involved in some of the things in Gettysburg just a month ago. There were lots of different lectures covering not only what you might expect – the campaign and battle of Gettysburg; I gave one of those myself – but also other kinds of social history things that we’ve been talking about. So I think there’s really an attempt to come to grips with more than just battles and generals and campaigns in connection with some of the sesquicentennial events.

Is that one of the ways you feel it contrasts with the centennial?

JM: Seems to, yeah. Exactly. I read some of the accounts of the centennial that say what a train wreck that was in certain ways. I think it’s being done much better this time.

You were a student at the time of the centennial, were you involved at all with it?

JM: No. Interestingly enough I got interested in the Civil War through the civil rights movement, which was of course contemporaneous with the centennial. That relationship is fascinating. I was struck by the historical roots of the civil rights movement in the abolitionist movement and the Civil War and Reconstruction period. That’s really how I got interested. Not through the centennial, but through the civil rights movement.

When did you decide you wanted to become a Civil War academic?

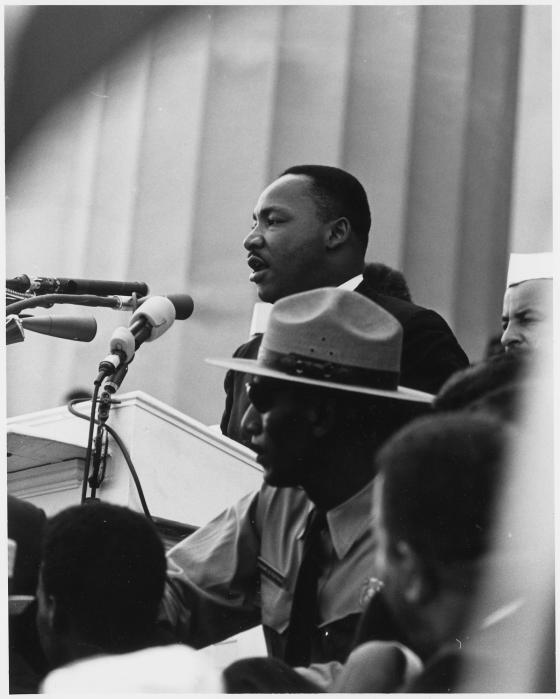

JM: It was pretty much in graduate school in Baltimore at Johns Hopkins, because that was right in the middle of the civil rights demonstrations. Baltimore is a border city, and there was all kinds of stuff going on there. And I was really struck by the historical parallels, right on down to the March on Washington - the anniversary of which is coming up soon, the fiftieth - where Martin Luther King connected the dots between the Civil War and the present with his ‘I Have A Dream’ speech which he gave at the Lincoln Memorial.

Didn’t King call on President Kennedy to issue a new Emancipation Proclamation?

JM: Yes, exactly. And I think, in some ways, Kennedy didn’t want to offend the southern wing of his party, so he didn’t do anything. But his failure to do anything, I think, had a lot to do with the decision by King and other civil rights leaders to go ahead on their own in August 1963.

You were already a student of history at that point. When did you make that decision?

JM: In college.

Had you always been interested in history?

JM: No, in high school I didn’t have any interests besides sports and girls! I wasn’t really challenged intellectually until I went to college. And it was a couple of history professors and an English professor who taught a course called “American Civilization” that really turned me on to history. So I decided to major in history, and then talking with professors decided to go to graduate school. But I didn’t have any particular Civil War interest then. In fact that small college in Minnesota didn’t have a Civil War course so I didn’t really get interested in that until I got to graduate school.

A lot of my friends who are in the field, people like Gary Gallagher, their interest in the field goes back to, in his case, reading the old American Heritage History of the Civil War Illustrated by Bruce Catton, which he read when he was eleven years old, I think, and was hooked. Probably by the pictures! But my route to becoming a Civil War historian was much different.

Is there anybody new that you’ve read, maybe a former student, who you think will make a name for themselves?

JM: I’ll tell you one. She is a former student, and an unusual one. Her name is Yael Sternhell, she’s Israeli; her father is a very prominent European historian in Israel and she takes after him. But her interest is in the Confederacy in the American Civil War; the South. Her doctorate dissertation and book was called Routes of War, and it is a very innovative study. It’s won two prizes now. It’s about the way in which the movement of peoples in the Confederacy shaped the Confederacy; shaped Confederate nationalism. The movement of soldiers from the Deep South to Virginia, slaves moving to freedom, armies moving across the land, deserters leaving the army, the government leaving Richmond; the way both Confederate nationalism was formed and then fell apart, in movement. There’s a whole scholarship that I knew nothing about, that she certainly mastered, about the way in which the movement of peoples over time and space has shaped cultures. She applied some of this theoretical work to a study of the Confederacy.

She now teaches at Tel Aviv University. There’s not a whole lot of American history taught at Israeli universities, so she has almost a tabula rasa there to create a field. She’s young, she’s in her thirties. I think her work has already made an impact in this country and I think she’s going to be one of the leading lights in the field, with an unusual perspective as well as an unusual residence.

Is there an area of history, aside from United States history, that you find particularly interesting?

JM: Well I took one of my minor fields in graduate school in modern German history, I think from 1870, the founding, through the end of World War II, and I’ve always been fascinated by that. I continued to do some reading in that field. And that has also given me a real interest in the New Deal and World War II in American history too because of the intersection of those two subjects there.

Some on the American Revolution too. Just living here in Princeton you absorb a lot about the American Revolution.

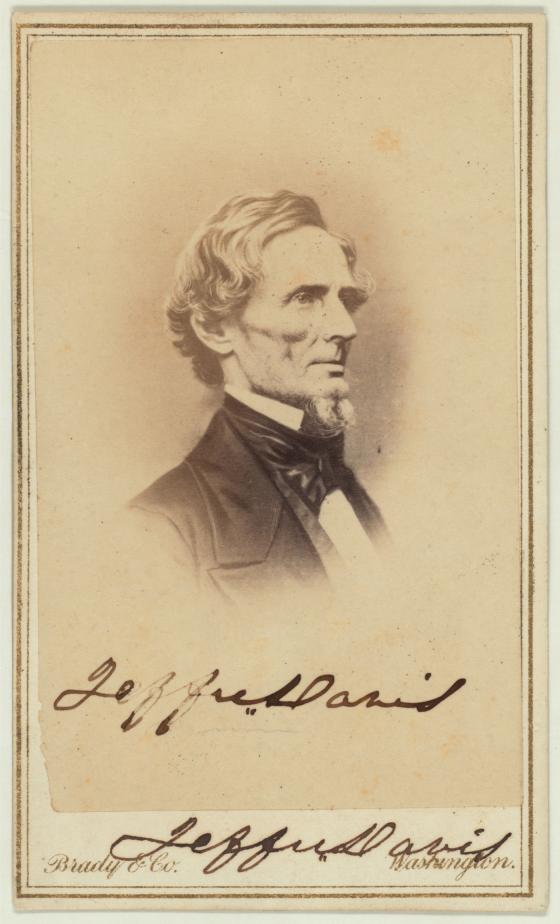

You mentioned that you were finishing a book on Jefferson Davis, specifically in his role as commander-in-chief.

JM: Yes, it’s a twin to my Lincoln book (Tried by War).

Can you share any insights?

JM: Yeah. I guess one or two things. Historians develop a degree of like and dislike for some of the subjects the study or write about, and I had always sort of been negative about Jefferson Davis, but the more deeply I dug into his role as president and commander-in-chief, the more I developed at least a degree of sympathy for him. Not necessarily because of any attractive personal qualities he had - and I think his qualities were very much a range of unattractive as well as some attractive qualities - but I found myself sympathizing more with him than some of his enemies within the Confederate establishment, which were many - people who thought they were better than he was, or hated him for one reason or another. I think he was usually on the right side of those internal controversies with people like Beauregard and Joseph Johnston, for example, and Robert Toombs - people who really developed something of a dislike for him. So that created a kind of perverse empathy, if not sympathy for Jefferson Davis.

As far as his qualities as commander-in-chief, I think probably it’s unfair to blame him for the mistakes that lost the war. He made mistakes of course, but as I say actually in the last sentence of the book: the salient fact about the American Civil War is not so much that the Confederacy lost it, but that the Union won it. And so much of the Jefferson Davis scholarship revolves around his responsibility for losing the war, and I tried to take a different tack. But I certainly don’t argue that he was some kind of military genius, or he was misunderstood in any kind of way.

Confederate historiography was full of the blame game. [If] you lose the war, somebody gets blamed, and Jefferson Davis is the usual target for the war as a whole. And I think that’s unfair, and I tried to – without necessarily being defensive towards him – make that a theme in the book.

My understanding of Davis is that he would have preferred to be in the field.

JM: Absolutely, whenever he had a chance he was out there. I think his wife is right in her memoir, when he got the telegram from Montgomery saying he had been chosen provisional president of the Confederacy his face blanched because what he was hoping for, and expecting, was maybe [that] he would be general-in-chief of the Confederacy. And in a way, that’s the way he functioned. He was not a good politician; he never pretended to be. He spent most of his time and energy dealing with the military aspects, more than Lincoln did I think. Whenever the fighting was near Richmond, he was out there.

When you look back, it seems like it was always going to be Davis [for president]. Was there anybody else considered?

JM: Well he was the consensus choice of the convention in Montgomery for provisional president. Part of the reason for that was probably that the three leading competitors for the job were all from Georgia, and they all undermined and stabbed each other in the back - Toombs, Howell Cobb and Alexander Stephens. And since the Georgians couldn’t settle on one of their own, and they were the largest state in the original seven that formed the Confederacy, and because the convention, I think realistically, expected war and Davis was the best qualified he seemed to be the logical candidate. It was a unanimous choice. There seemed to be no viable alternative. And of course when he ran for election – to be constitutional president of the Confederacy rather than provisional – he ran without opposition.

Can you see any facet of the Civil War that is crying out to be further scrutinized?

JM: It’s really hard to think of any aspect that hasn’t been, because it’s been so thoroughly mined, even down to such a thing as children’s literature during the Civil War. Jim Martin has done a couple books on the impact of the war on children. There might be more room for demographic studies of the kind that David Hacker recently did, that raised the estimate of the number of dead to 750,000. I think he began a conversation, and maybe there can be some more work done along those lines. I’m not quite sure if anybody is doing it. And of course Drew Faust’s book about the impact of death, I think there may be room for more of that. She may have begun something that other people can [further]. The history of memory is also another subject that David Blight opened up that other people are going to be doing.

Do you have one work that you are most proud of?

JM: I suppose Battle Cry. It took several years out of my life, and continues to do so in some ways!

The title sort of sums it all up really, that both sides were singing basically the same song. Both thought they were fighting for freedom.

JM: My wife came up with that title. We were throwing around – Van Woodward and Sheldon Meyer and I, and my wife – sitting around our dining room table after I had finished the book but before I had come up with a title for it. She’s the one who suggested that. I had some other ideas that I’m glad we never followed up on, like ‘American Armageddon.’ That was one of my working titles for a long time, but I was talked out of that. The only one that was initially skeptical about [Battle Cry] was Van Woodward, because he thought it sounded too Yankee. So I went through the whole bit with him and showed him the southern version.

He was very broad-gauged. He let us, as students, do what we wanted; to pick the subjects we wanted and take the point of view we wanted. He was a good critic, but he didn’t try to channel us in any particular direction. Woodward was very laissez-faire as an advisor. I think he was a little skeptical of my project, looking at the abolitionists during and after the Civil War. I got very interested, in the first couple years of graduate school, in the Dunning School of Reconstruction historiography and the reaction to that that was going on in the 1960s. New studies of Reconstruction had challenged the old Dunning interpretation, and I was going to do a dissertation on Alabama Reconstruction that would’ve challenged the Walter L. Fleming book on Alabama – he was a Dunning student. And I turned in a couple of graduate research papers on that subject, but I grew increasingly negative about the idea of doing two, three, four years of my life doing research in Alabama, about Alabama in the early 1960s. I got more and more interested in the abolitionists because, as I said, of the civil rights movement that was going on. The more I learned about the abolitionists the more I thought that they were the civil rights activists of their time. There was almost nothing in the literature about what they had done after 1861. All of the literature on the abolitionists then was the 1830s, ‘40s and ‘50s. So I thought: ‘did these people disappear into the woodwork?’ And Woodward was initially kind of skeptical about that subject but he warmed up to it.

You’ve called the Civil War ‘the war that never goes away.’ How would you explain why the Civil War is still so compelling?

JM: Well, I think there are several explanations for it. [One is] the colorful personalities that are involved and that loom so large in our historical consciousness. Lincoln and Lee, for example, but many others – Grant, Sherman, Jackson, Clara Barton, Jefferson Davis himself, Frederick Douglass. All those people seem to be sort of giants. So that’s part of it. The huge impact that the war made on the consciousness of the country at the time, on several levels, the massive death being one of them. If you translate even the lower estimate of 620,000 deaths in the war, that would be the equivalent of more than six million in a war fought today. And just think about the way in which that might be viewed one hundred and fifty years from now. But then, the reason I got interested in it is another reason why it doesn’t go away, and that is the issues over which it was fought are still important in American life today. Just look at some of the controversies over the Obama administration and its policies. If you impose a map of, especially the 2000 and 2004 elections, on a map of the Civil War, the red states were Confederate states or were not yet states, and the democratic states, the blue states, were the Union. Now, Obama cut into the southern states a little bit in 2008, so the maps don’t look quite as clear but otherwise, the geographical division of the country is not so dissimilar from what it was a hundred and fifty years ago. The issues, if they’re not exactly the same, are certainly related in some ways. At the time of Obama’s election and inauguration there were constant comparisons to Lincoln and the Civil War. So that’s another example of why it stays fresh and alive.

James McPherson was born in North Dakota and raised in Minnesota, where he graduated from Gustavus Adolphus College in 1958. He received his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University in 1963. From 1962 to his retirement in 2004 he taught at Princeton University, where he is currently the George Henry Davis '86 Professor of American History Emeritus. Several of his books on the era of the American Civil War have won prizes, including the Pulitzer Prize (1989) for Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era and two Lincoln Prizes (1998 and 2009) for For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War and Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief. He has been associated with battlefield preservation since he first joined the board of the Association for the Preservation of Civil War Sites back in 1990. He has served as president of the Society of American Historians and of the American Historical Association. He is currently working on a book about Jefferson Davis as Commander in Chief.