An Introduction to the Quaker Influence During America’s Founding

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, the American colonies had coexisted under the umbrella rule of the British government. Among the many leniences granted to the North American colonists was the wide-birth in religious assembly. No single religious affiliation was granted governorship over the rest of the citizenry, though some did have tremendous influence. For our understanding, the focus will discern one of the most prominent of these several affiliations. And we will see how their proximity to Philadelphia would come to shape how the United States came to be.

Out of the many complex issues surrounding the delegates to the Second Continental Congress in 1775-1776, perhaps the single biggest issue regarding how to respond to Great Britain’s increasing taxation and authority over colonial governments was how regional influences impacted the solutions being presented in Philadelphia. Puritanism was still deeply rooted in the New England colonies and the delegates from that region, at the time the most embroiled in the rebellion, defined much of their opposition to British aggression through the lens of their congregate upbringings. Eastern Pennsylvania and portions of West Jersey (New Jersey was then divided between two unofficial regions: East and West Jersey) were heavily influenced by Quakers. Commonly known as Friends in the community, and for their industrial presence and political connections that dated back to William Penn, leadership was very organized in most branches of local government. They were also well-known for their pacifism. Puritans had long-held animosities towards Quakers because of their differences in practicing their religious faith. Others saw members as British sympathizers. These sharp opinions would rupture in various ways during the debates leading to American independence.

The Quaker leadership of Pennsylvania in the First Continental Congress was divided between rivals Joseph Galloway and John Dickinson. Though both men were technically not practicers of the faith, they served in the same political assemblies as them and often agreed with agenda proposals. Neither were considered radicals such as the Adamses of Massachusetts, but Dickinson, the moderate voice of the two Pennsylvanians, won over many with his cool demeanor and eagerness for finding a solution. On the other hand, Galloway’s Plan of Union, which called for the creation of a Grand Council subordinate to Parliament, won little support from the First Continental Congress. His popularity and influence diminished after he alienated delegates who refused to endorse his vision of appeasement, and soon he began attacking in the press those who envisioned a separation from London. When the Second Continental Congress met in 1775, Galloway refused to accept his nomination, opting to remain outside the body and attack its deliberations. He would later side with the British during the American Revolution.

John Dickinson was perhaps one of the most famous Americans to attend the Second Continental Congress. His notoriety proceeded him following a series of pamphlets he wrote in 1767-1768 titled, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, which criticized Parliament’s taxation on the colonies. As stated, Dickinson himself was not a member of the Society of Friends, but his mother and wife were practicing members. The original affirmation John Adams had shown for Dickinson began to unravel during the Second Continental Congress. Dickinson had been respected for his proposals in 1774 and would write the Olive Branch Petition in the summer of 1775 to try and express the desires of the colonies to remain loyal to the British government, with grievances to be addressed. However, Dickinson’s calls for neutrality and reconciliation with Parliament were formerly disrupted when word reached Philadelphia in January 1776 that King George III had declared Massachusetts and the colonies in a state of open rebellion against the Crown following the events in April-June 1775. It was now clear that war could not be prevented.

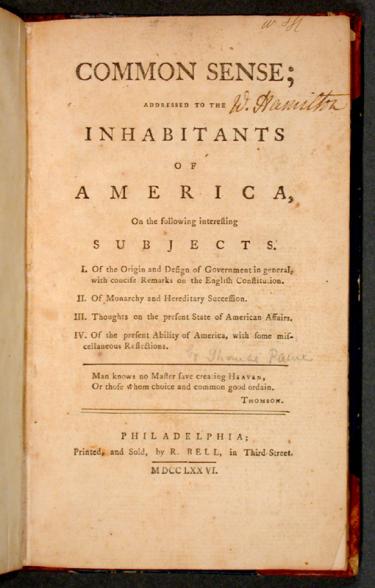

Thomas Paine would write and publish Common Sense in January 1776, which more than anything else turned the conversation from reconciliation towards independence for many Americans. Paine used biblical language (as the Bible was the single-most read book at the time) to denounce British sovereignty over the colonies. He also used it to great effect to criticize organized religions, particularly Quakerism, who did not see American independence as the only legitimate way forward. Paine successfully created an air of skepticism aimed at those who would oppose separation. Plain Truth, the pamphlet written in response by loyalist James Chalmers, was whispered by some to have been the work of Dickinson. This accusation further alienated his once-respected modernity as another obstacle that stood in the way of the radical’s plan for independence. Resolutions were drawn up in Congress to respond to the King’s proclamation failed. Dickinson’s held out the belief that there was a way to reconcile with the King was now being openly questioned as a diversionary tactic by some in Congress, including John Adams.

The Pennsylvania delegate continued to straddle a fine line between supporting the American colonies and his personal advocacy for smoothing over hostilities with London. In February 1776, he requested to be given command of Philadelphia militia units if they ever had to defend the city from British forces. But this show of patriotism did not win him accolades. In June, Dickinson was among several delegates who opposed Virginia delegate Richard Henry Lee’s resolution calling for the colonies to declare their complete independence from Great Britain once and for all. Dickinson spoke to the gathered body and remained convinced that their tired efforts for reconciliation were not in vain and would produce the results they sought, eventually. Lee’s resolution forced several new debates over what to do next. Opposition to independence remained strong in Congress, despite a clear momentum forcing some decision to be made on the subject. A committee was formed to write out a declaration summarizing independence. Dickinson, in the meantime, served on several committees that determined a continental foreign policy moving forward. A final decision had been tabled until July 1.

It was on this day, July 1, 1776, that saw the ‘great debate’ reach its crescendo. John Dickinson, summarizing the caution and prudence of reconciliation, spoke first. He recalled the great advantages they had all shared as subjects of Great Britain, and that time would guide their resolve to seeing to it their grievances would be answered. John Adams spoke second. During a terrific thunderstorm, without any prepared notes, he rallied the room for American independence. A vote carried out after he finished did not produce enough consensus to declare independence, however. The following day, July 2, Dickinson, along with fellow opposer to independence Robert Morris, abstained from voting with the rest of the Pennsylvania delegates. Their removal allowed the remaining five members, including Benjamin Franklin, to vote 3-2 in favor of independence, thus changing the mood of deadlock in the room, and helping to secure American independence. James Wilson, a fellow Pennsylvanian delegate, cited his reversal to vote in favor of independence being influenced by the will of the people. We are not entirely sure, but perhaps this persuaded Dickinson to abstain.

Dickinson would go on to be a major supporter of American independence during the Revolution, briefly taking command of troops in New Jersey before returning to political work. He served as president to the Delaware and Pennsylvania State Assemblies and served as a delegate from Delaware at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. He was also one of the first early abolitionists to free his slaves, echoing the emerging abolitionism among Quakers, and seeing it as upholding the principles of the American Revolution.

His role during the years and months leading up to independence in July 1776 served as a counterweight to the radicalism that propelled many of the debates towards the decision to separate from Great Britain. And to understand these sentiments, one cannot overlook the regional influences that shaped each delegate. As shown, Dickinson was largely a moderate who sought reconciliation not because of a deep loyalty to British authority, but because of a deeper hesitation of the unknown. Less militant than other religious faiths at the time, the Society of Friends preached passiveness among its highest virtues. Dickinson’s actions speak of these influences and thus show to us an important feature among the reasoning behind the debates that led to American independence.

Note: Readers can see a semi-fictionalized retelling of the drama between John Dickinson’s reconciliation and John Adams’s independence in the HBO miniseries John Adams. Episode 2 is devoted to the years 1774-1776.

Further Reading

- The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution By: Bernard Bailyn

- Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor: The Forging of American Independence, 1774-1776 By: Richard R. Beeman

- The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin By: H.W. Brands

- Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence By: Joseph J. Ellis

- Party Politics in the Continental Congress By: H. James Henderson

- The Founders on the Founders: Word Portraits from the American Revolutionary Era By: John P. Kaminski

- Founding Faith: How Our Founding Fathers Forged a Radical New Approach to Religious Liberty By: Steven Waldman