In the spring and early summer of 1862, Union General George B. McClellan floated the Army of the Potomac from Washington, D.C. to the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, made an amphibious landing, and advanced overland until the spires of Richmond could be seen from his forward camps. One Union victory—the “American Waterloo” that McClellan claimed to seek, and the war could have been over.

Then Robert E. Lee took command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and, in a frenzied campaign, drove McClellan’s forces away from the capital and back towards the sea. By July, Federal hopes were firmly dashed, and the Confederacy was enjoying a surge of momentum and morale.

Into the Northern miasma swaggered General John Pope, a winner of some victories in the West, to take command of the newly-formed Union Army of Virginia. The army was made up of three corps, each of which had operated unsuccessfully against Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley in the spring.

“Let us understand each other,” Pope told his uneasy soldiers on July 14, “I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense…. I desire you to dismiss from your minds certain phrases, which I am sorry to find so much in vogue amongst you. I hear constantly of ‘taking strong positions and holding them,’ of ‘lines of retreat,’ and of ‘bases of supplies.’ Let us discard such ideas. The strongest position a soldier should desire to occupy is one from which he can most easily advance against the enemy. Let us study the probable lines of retreat of our opponents, and leave our own to take care of themselves. Let us look before us, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.”

Along with this pronouncement, the Kentucky-born Pope drafted a set of general orders concerning the Virginia citizenry. The salient points were these:

- The Army of Virginia would feed itself by taking supplies from the local farmers. The farmers would be presented with a government voucher that would be redeemable at the conclusion of the war, but only if they could provide witnesses to prove that they had been loyal to the United States since the date of the voucher’s issuance.

- If a guerrilla force harmed the Army’s lines of communication (by rail, bridge, or telegraph) all citizens within five miles of the incident would be turned out to repair the damage, and would be forced to pay and feed the Union guards overseeing the labor.

- If a guerrilla force harmed a Union soldier, all citizens within five miles of the incident would be forced to pay a fine. Any citizens believed to be actively involved in an attack would be “shot without awaiting civil processes.”

- All male citizens would be arrested and compelled to either take an oath of allegiance or be exiled farther south, outside of the Army’s lines. If a man was judged to have violated his oath, or if he attempted to return home, he would be shot or hanged and his property would be confiscated.

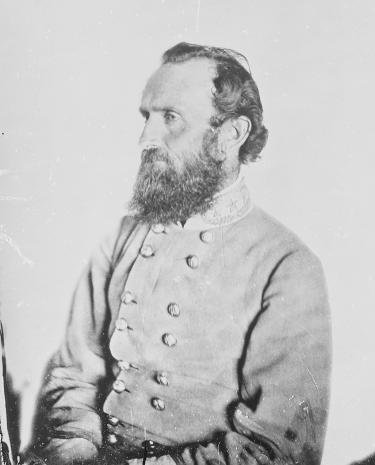

With such matters established, Pope began to prepare his offensive. The first objective would be the rail junction at Gordonsville, Virginia. Located on the south side of the Rappahannock River, the strong and stubborn natural barrier that flowed almost exactly halfway between the rival capitals, the town would serve as a base of operations for the finishing blow on Richmond. It was garrisoned by Stonewall Jackson and 10,000 Confederates.

When Robert E. Lee read newspaper reports of Pope’s treatment of his statesmen, he experienced a rare burst of overt anger. “The course indicated in his orders,” he wrote to Jackson on July 27, “cannot be permitted. You had better notify him [at] the first opportunity.” To drive his point home, Lee dispatched the fiery General A.P. Hill, who had grown up only a few miles from Gordonsville, and 14,000 men to Jackson’s aid.

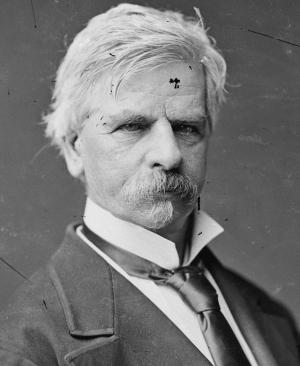

On August 6, the Union Army began to move in earnest. Pope placed his Second Corps, some 8,000 men under politician-turned-general Nathaniel Banks, in the lead. On August 7, Jackson left Gordonsville and marched north, hoping to meet and defeat Banks, who he had thrashed in the Shenandoah Valley at the First Battle of Winchester in the spring, before the rest of Pope’s army arrived.

Both forces moved slowly, the men suffering in the unusually severe heat. An Indiana private remembered seeing comrades “lying on the ground frothing at the mouth, rolling their eyeballs and writhing in painful contortions.”

Confederate officers were frustrated by Jackson’s penchant for secrecy, which led to frequent confusion and delays as his columns struggled to maintain a fighting formation without knowing their ultimate destinations, and with hardly any knowledge of the movements of the units around them.

Speaking to his staff, Jackson did divulge one bit of intelligence: “Banks is in our front, and he is generally willing to fight. And he generally gets whipped.”

By the morning of August 9, Banks and Jackson were in fighting range around Culpeper Court House. Banks halted and positioned his corps along a ridge near the foot of Cedar Mountain and astride the Culpeper Road, Jackson’s most likely avenue of approach. He deployed his cavalry, under the command of French adventurer Alfred Duffie, roughly 1,400 yards southwest of his main line. Duffie’s troopers watched keenly as clouds of dust began to rise from down the Culpeper Road. Jackson was coming.

General Jubal Early’s brigade was the leading edge of Jackson’s column. Scouting ahead through woods that concealed the Confederate advance, the irascible but skilled Virginian soon discovered Duffie’s cavalry screen. He hastened back to his soldiers and directed them off of the Culpeper Road. Moving southeast through the trees, Early’s men suddenly appeared off of Duffie’s left flank and unleashed a crashing volley.

Confederate cannons added their iron to the contest and the cavalrymen began to fall back. Duffie galloped along his line, bellowing oaths and commands and trying to rally his shaken troopers. In that critical moment, however, one of his subordinates issued a mistaken order that caused the formation to splinter once more. Duffie charged up to the man and screamed, “what a sickness, what a business; I be like you--I go buy one rope, I hang myself!” But the damage was done and there was nothing that could stop the retreat this time. “Old Jube” Early had secured a foothold on the battlefield.

Jackson's force was crowded onto one road to approach Banks's position. It took more than five hours for the rear of the column to reach the battlefield. (Map taken from the upcoming Cedar Mountain walking trail)

Now the Union artillery opened fire. More Confederates were approaching. The trees that had concealed the advance cleared up around the “Crittenden Gate,” the gated intersection of the Culpeper Road and the Crittenden family farm lane. The Union guns focused their fire there as the junction became filled with grey-clad soldiers. Shell-bursts hurled shrapnel into the crowd and men dove for cover—creating an even more deadly logjam.

Some men, however, doggedly pushed forward. Virginia private William Patteson told a comrade, “I have come to help whip the Yankees and would not take a thousand dollars for my chance to help whip these devils who have destroyed our home.”

Slowly, the grey line took shape. It stretched north and south of the Culpeper Road, extending considerably further to the south, where it climbed the slopes of Cedar Mountain itself. Batteries rumbled to the front and began to exchange a heavy fire with their Union foes across the field.

General Charles Winder, a former artillery officer now commanding Stonewall’s famed old infantry division, enthusiastically took command of the Confederate cannons near the Crittenden Gate. He told the men around him to stick to their work and to refrain from helping wounded comrades.

As Winder leaned to shout an order over the booming sound of the guns, he was struck by a Union shell. Cannoneer Ned Moore remembered that the shell “passed through his side and arm, tearing them fearfully. He fell straight back and lay quivering on the ground.” Remembering Winder’s orders not to help wounded men, Moore returned to working his gun. Nevertheless, Winder was soon placed on a litter and hurriedly shuttled towards the rear. He would die in a schoolyard several miles down the Culpeper Road.

The artillery duel continued for two hours with neither side gaining an advantage. Some gunners were felled by heat stroke as they feverishly operated their pieces. Major George Wood of the 7th Ohio, in position near the Union batteries, remembered that “the boys threw themselves upon the ground…with a hail-storm of grape, canister, and shell falling thick and fast around them….During that fatal period death assumed a real character, while life seemed but a dream.”

The artillery fire plunging around the Crittenden Gate had severely disrupted the Confederate deployment, and many Southerners were still struggling to get into position when Nathaniel Banks opted to send his infantry forward. He led off with General Christopher Augur’s division, which launched an attack through the fields east of the Culpeper Road.

Augur arranged his eight regiments into two massive lines, one behind the other, and pressed his men forward through a thick cornfield. Confederate cannons on Cedar Mountain sent solid shot bounding through the blue ranks as bullets whistled through the corn, cutting down the stalks “as if with knives,” according to one Union soldier.

The firing intensified as Augur’s men neared the Confederate line. A small declivity and a split-rail fence shielded the Southern riflemen and the Federals, fighting without much cover save for that offered by the cornstalks, were getting the worst of the shooting match. Augur himself went down, shot through the foot.

In an untenable position, the Union infantry attempted to resolve the crisis with a bayonet charge. This charge, however, like most bayonet charges during the war, did not quite strike home. Seeing that the grey-coat veterans were not tumbling backwards in fear, the blue line slowed, halted, and poured in musketry from closer range.

This process was repeated as many as nine times over. The Confederates wavered briefly, but Jubal Early galloped onto the scene and re-energized the defenders. Seeing that no further progress could be made, Augur’s men grudgingly withdrew back towards their starting positions.

With his first effort thwarted, General Banks ordered a fresh attack north of the Culpeper Road. General Samuel Crawford, who would go on to command the Pennsylvania Reserves on Little Round Top, spearheaded the assault with his brigade of New Yorkers, Pennsylvanians, Connecticutans, and Mainers.

Augur’s men had struck the Confederate center, and as such they had truly gone into the teeth of Jackson’s position, exposed to fire from all sides. Crawford’s attack was aimed at the Confederate left and was subject to no such crossfire. In fact, the secessionists in this sector belonged to Winder’s division, and the loss of their commander left the units without the coordinating influence needed to build a strong defensive position. As things stood, the reserve line was posted too far behind the first line, and the extreme left flank was unsecured.

Crawford’s men advanced through a wheatfield in battle line, overlapping the Confederate flank by a considerable margin. When the firing began, the Southerners found themselves outnumbered and out-maneuvered. After a brief struggle, the first line crumbled and men began to flee south through the woods.

The triumphant Federals wheeled and struck the now-exposed flank of Jackson’s center elements. The musketry was heavy and close, both sides taking severe casualties. Winder’s reserve line came up and swept the Federals with aimed fire, sapping some of the momentum of the advance. But the Confederate center was starting to give way.

And then Jackson himself arrived, his horse kicking up gravel and splinters. Bullets whizzed all around, and men were fighting hand-to-hand to the death in the smoky woods. The blue-eyed Virginian skidded to a halt and grabbed a battle flag from one of his soldiers. He lifted it above his head and then tried to draw his sword, but it was rusted into its scabbard--he had never before drawn his sword in battle. Unperturbed, he raised the blade, scabbard and all, and shouted, “Jackson is with you!”

The scene was awe-inspiring. Even nearby Union prisoners cheered. The Confederates steadied and began to push back against the blue tide. Jackson’s stand bought valuable minutes—A.P. Hill’s division was just then coming up the Culpeper Road.

Hill pushed his regiments into the fight without taking time to halt and form line. Now it was the Federals who were outnumbered. More of Hill’s men arrived, sweeping around to the west and north and threatening to surround the worn-out Union soldiers. The momentum of Crawford’s attack was broken, and his men began to retreat with the Confederate reinforcements right behind them. Seeing the Union repulse, more Southerners advanced off of Cedar Mountain and added their weight to the counterattack.

As the pursuit spilled into the wheatfield, the 10th Maine Volunteers mounted a desperate rear-guard action. They had no chance. Hill’s men greatly outnumbered the Mainers and shot them down in scores. Horace Wright saw his son Lyman fall, his arm torn apart by a Minie Ball. “I will try to compose myself to write you a few lines to let you know how we are but you must prepare yourself for the worst…” he would write to his wife, “it near breaks my heart to see my poor boy with but one arm and to be a cripple for life but it is so…”

The 10th Maine retreated. Nathaniel Banks ordered a cavalry charge, but rifle fire emptied many saddles and the attack broke apart before coming close to the advancing Confederates. Confederate cavalrymen pursued the fleeing Union troopers for more than a mile and burst upon Banks’s headquarters, shooting several staff officers before withdrawing.

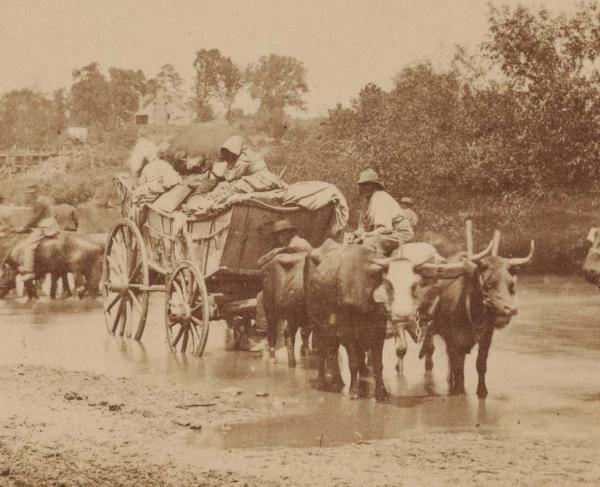

Survivors of the 10th Maine returned to the scene of their brave stand shortly after the battle. Note the dead horse at right--the first photographs of dead horses on a battlefield were taken at Cedar Mountain. (Library of Congress)

Only the arrival of General James Ricketts and his fresh division staved off a total Union disaster. His men formed for battle near Banks’s cannons and the Confederates, weary from a long day of marching and fighting, chose not to test this menacing new position with an infantry assault. The artillery fight raged until after nightfall.

Stonewall Jackson held the field for three days before returning to Gordonsville. It had been a close-run and bloody victory—each side suffered roughly 1,400 casualties. It was enough to spook Union General-in-Chief Henry Halleck, who from his Washington, D.C. office ordered John Pope to suspend his advance on Gordonsville.

The Battle of Cedar Mountain robbed the Union Army of its momentum and left it drifting in hostile country. Later that month, Robert E. Lee would seize the initiative and defeat Pope's army in its entirety at the Battle of Second Manassas.

In fall 2013, the Civil War Trust will be lengthening and enhancing its 1.25 mile walking trail with new interpretative signs. As of 2013, the Civil War Trust has saved 165 acres at Cedar Mountain—the majority of the battlefield—including the sites of the Union attack, Winder’s wounding, and Jackson’s stand—which Jackson himself considered to be the greatest of his martial exploits.

Related Battles

2,353

1,338

14,462

7,387